During history, there were always migrations of educated and other people, primarily from less developed to more developed, richer countries. Now, in the post-industrial period, migrations are observed, particularly in terms of the consequences for countries losing some of their highly educated and skilled human capital, which is essential for dynamic economic growth and sustainable development. Not surprisingly, as these flows are rather intensive, over the last few decades, the concepts of “brain drain” and “brain gain," with their economic, social, and political consequences, have been introduced and discussed increasingly. Some of the studies and articles are objective and certainly valuable, while some others could not be separated from the vested interests of the brain-gaining countries.

During colonial times, it was normal that highly educated people in the “overseas territories” were leaving their countries in substantial numbers and moving to the metropolises, benefiting from incomparably better conditions of work and life.

Massive migrations have also been experienced in other contexts and periods, either as a response to antisemitism in a number of European countries or due to Nazi policies before and during the Second World War, as well as escaping from Russian totalitarianism. It also took place during the Cold War pressures in Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, even after that, millions of well-educated workers in Europe’s east and south-east have left for Western Europe and North America.

It is, however, necessary to distinguish between politically motivated migrations and those based primarily on the difference in economic conditions, offering migrants much more favorable career prospects and better possibilities to create their own companies. Much of these migration flows, being facilitated and even actively stimulated by the recipient countries, have gradually started to be referred to as the “brain drain.”

Which are the main categories of modern brain drain?

- Migration of highly educated workers in search of better conditions (salary, as well as career prospects);

- International students not returning to their home country;

- Politically-motivated migration of educated workers;

- Other – including a combination of the above.

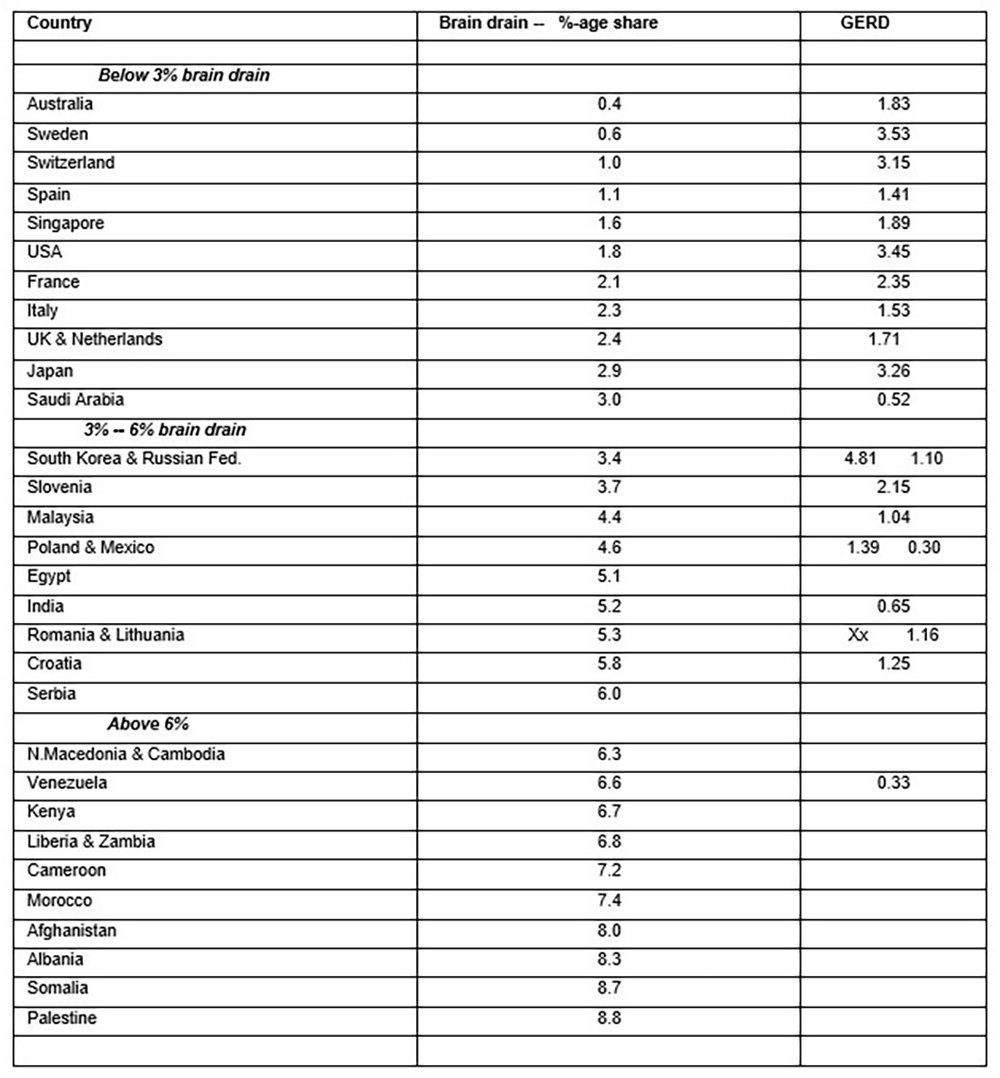

There are obvious advantages for individuals leaving their countries of residence in order to get a better-paid job, often with prospects for promising careers in a superior professional environment. But at the country level, there are serious losses faced by those countries, losing parts of their valuable human capital, in the building of which they have invested billions of public funds. Though the table below demonstrates that brain drain represents different shares of individual countries’ populations (between 0.4% and 8.8%), the World Bank estimates that the loss of human capital via brain drain globally represents for the countries losing these people annually a cost of 69.2 billion USD.

Comparison of brain drain and Gross Expenditures for R&D – selected countries 2017-2018:

Source: World Population Review, Brain Drain Countries 2023.

Source: World Population Review, Brain Drain Countries 2023.

For the rich countries, their loss of brains is more than compensated by the influx of quality human capital from other countries. Therefore, these countries are net gainers in the process, which they understandably refer to as “brain circulation.”

It would be interesting to compare the total number of inbound vs. outbound students globally, but unfortunately, many countries are not publishing the statistics of their citizens studying abroad. Based on official figures for 21 countries receiving the majority of foreign students, this number for the academic year 2022-2023 was over 5 million. But for the assessment of the relationship between inbound and outbound students, we can use only the available figures for 13 countries, and there we come to the proportion of 3.6 million inbound vs. 1.4 million outbound. Not surprisingly, there are 2.5 times more students coming to advanced countries than their own citizens leaving to study abroad. Also, it is important to emphasize that these students are not contributors to brain drain, as they normally return home after graduation.

How big is the category of students from developing countries and Eastern Europe studying abroad, mostly in OECD countries? In total, it goes well beyond 5 million (with the biggest share studying in the US, Canada, UK, France, Germany, China, and Japan). The outbound student figure for 13 main countries is just below 700,000, which gives the proportion between inbound and outbound students about 7:1 in favor of inbound students.

With some exceptions, something like half a million of these students actually decide to stay and not return home. In a recent survey by ICEF Monitor in the US, only 13% of 1,087 foreign students expressed their strong position about going home after graduation. In practice, the situation is better than that, although recipient countries allow students to stay after graduation for a couple of years (the UK, for example, allows 3 years, while most countries offer such possibilities for a year or two). This is obviously a measure supporting the trend of graduated students staying and delaying or even refusing to return to their home countries.

In Germany, there is a special fund to support students from developing and Eastern European countries with fellowships (approximately 450 being offered) to study in Germany, under the strict condition of the funded student’s return to his or her home country after graduation.

For the developing countries, the loss of their valuable brains is definitely painful, and it is higher than the total value of the development assistance they are actually receiving (which was supposed to be, according to the decision made in 1964 in the framework of the UNO, at least 1% of developed countries’ GDP but remains at half of this level). There is no way of hiding from the fact that brain drain is actually a new form of international redistribution of income, benefiting the rich and depriving poor countries of the results of their investment.

The best illustration of this shameful situation is the health sector. At present, the rich Western countries are short of about 7.2 million health workers (by 2035, this figure is expected to reach even 12.9 million). Most developing countries and countries in Eastern Europe are facing a similar, if not even worse, situation that is further deteriorating because the rich countries are openly and systematically inviting the health workers to leave their home countries and take employment in rich countries, reducing the lack of personnel. These flows are consequently rather large: every fourth doctor trained in Africa is currently working in OECD countries, and in the UK, even 1/3 of doctors and about 1/5 of nurses have come to Britain from other countries, mostly from former British colonies. This is predominantly (estimated in about 70% of cases) a result of active campaigning and invitations from the recipient countries, affecting developing countries and countries in Eastern and South Eastern Europe. Undoubtedly, this practice cannot be labeled otherwise than a form of neo-colonialism and is morally unacceptable since it leads to many unnecessary deaths and suffering among patients in former colonies and other countries. Legally speaking, this practice is also in conflict with the Code of Conduct on International Recruiting for Health Workers, adopted back in 2010 by the member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva.

In our globalized world, things are more connected internationally than ever before. Not investing sufficiently in education, the EU countries are expecting to have a shortfall of 20 million skilled workers by 2030, which the poorer countries will help to bridge by experiencing brain drain.

What is the cost of brain drain to developing countries as suppliers of skilled workers to rich countries? India supplied in 2017 to the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia 69,000 doctors and 56,000 nurses, and the UNDP Report for 2001 estimated the cost of brain drain for India (with some 30 million working abroad) to be about 2 billion USD annually. However, as poverty is a major challenge for India, the rising level of remittances should also not be underestimated, as the official estimate for 2022 was about 100 billion USD. This certainly helps the 300–400 million poor citizens meet their basic needs. The Indian GDP for 2022 was 3.3 trillion USD, meaning that remittances represented about 3% of the GDP. This shouldn’t be directly compared, but it is even 4.5 times more than India gives for research and development (GERD being 0.7%).

All remittances coming to Latin America and the Caribbean countries by their ex-patriots working abroad are now probably about the same (in 2002, they were 32 billion USD). It varies from country to country, but the dependence on remittances is quite high for several poorer Caribbean countries (Jamaica at 18%, Guyana at 12%, and Grenada at 5% of their GDP), finding themselves in a situation resembling the one from colonial times.

An important segment of brain drain is when students are sent abroad on government expense or on their families’ budgets and decide not to return home. Their numbers unfortunately increased quite strongly: in 1976, their number was estimated globally at 0.8 million; in 2005, they were already 1.6 million; and in 2020, they were already over 2.5 million.

In a survey among 1,087 students at US universities from over 100 countries, 40% expressed interest in staying in the US for a few years after graduation, and 30% wanted to stay in the US for a longer period. Only 13% stated that they wanted to return home after graduation. This gives a picture of the challenge, but the latest indications are that fewer students actually stay in the US; this drop is somewhat bigger than for students doing their studies in European countries.

What should be done to address the problem of brain drain effectively? There is no doubt that the challenge is so serious that the countries losing their brains alone cannot achieve satisfactory results, though they can do a lot, and so far this has not happened yet—at least by most of the affected countries. But international organizations can do more as well, partly by adopting appropriate acts discouraging brain drain as well as strengthening the political will to address the issue more effectively than in the past. And what should and could the beneficiaries of brain gain do after accepting the understanding that uncontrolled brain drain seriously undermines broader efforts to reduce the global North-South divide?

When looking for measures to be taken in order to reduce brain drain, one has to carefully evaluate the very reasons for the phenomenon in a particular country or region. Here is the first test of whether the responsible authorities are capable and willing to make this effort critically, since it implies some of their responsibilities for the conditions that generate brain drain. The general conclusion about these conditions, compared to those in countries where people migrate, is that there are differences in economic, employment, and social circumstances. The bigger these differences are, the stronger the incentives for migration. Though this may sound simplistic, governments and societies interested in reducing or even eliminating emigration simply have to undertake all possible measures to reduce these differences.

Let us summarize what the countries suffering from brain drain should undertake in addressing the problem:

- For the start, authorities, political parties, NGOs, and the media should enhance public awareness about the seriousness of brain drain. This is the precondition for them to be able to introduce and support the efforts necessary to put the issue on the public agenda. Usually, people are not fully aware of the dimensions of brain drain, its cost, and its consequences. When the public and particularly the political class have been presented with the facts and the impact of the problem, the politicians will be in a better position to propose actions and undertake adequate measures to address the issue.

- When people recognize that efforts are being made to improve economic conditions, which implies also better career prospects, as well as that knowledge and skills are being recognized and rewarded, as a direct result, much fewer people will contemplate leaving the country. This has been proven in many cases, and it should not be forgotten that a decision to leave one’s home country is one of the most difficult ones in a person’s life.

- However, government declarations are not enough to persuade people to stay in the country when they are dissatisfied with economic and other conditions. People want to see action and promised improvements going into all domains of a more prosperous, welfare state based on a knowledge-intensive, competitive economy.

- This covers a broad range of policy domains, starting with affordable, quality education, an employment regime, health services, strongly supported R&D, and entrepreneurship.

- The impact of several policies with the potential to reduce brain drain is reflected in the in the improvement of a country’s international ranking on innovation performance.