How are design products styled and staged? How do designers, photographers, graphic artists and companies work together to promote them? When were the first graphic and photographic advertisements produced?

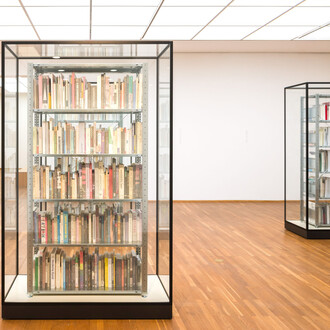

Like no other, the collection of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G) enables a juxtaposition of design objects and their staging in graphics and product photography. The exhibition Hello image: the staging of things explores the collaboration between creative talents from the fields of design, photography and graphic art and presents the design of the products and their staged image from different perspectives. Around 20 case studies tell the stories behind prime examples of product and advertising design from the early twentieth century to the present day.

The exhibits on display include design classics such as Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s Bauhaus lamp and the "Valentine” travel typewriter conceived by Ettore Sottsass and Perry A. King. Joining them are fashion icons such as the down “Duvet coat” by Martin Margiela and an elegant dress in Issey Miyake’s signature pleats, alongside well known photo series by Lucia Moholy and Juergen Teller and key graphic works by Giovanni Pintori and Otl Aicher. The show also presents exciting discoveries, including works by the illustrator Lora Lamm, the designers Margarete Jahny and Erich Müller, the photographer Ingeborg Krach Rams, and the graphic artist Wolfgang Schmidt.

Exhibition chapters

The chapter Graphic design or photography? traces the historical transition from typography and graphics to photography in advertising using the example of Kaffee Haag. Until 1925, graphic art by Alfred Runge and Eduard Scotland shaped the brand’s image, but then Kaffee Haag’s collaboration with Albert Renger-Patzsch, one of the most renowned photographers of his day, ushered in the use of the new medium of advertising photography.

Finding a new form looks at the design developments brought about by the use of new materials such as glass and metal and the associated pared-down design language of the 1920s to the post-war period. Contemporary photography celebrated this new formal clarity. In photography, this new clarity of form was celebrated by photographers such as Albert Renger-Patzsch and Hans Finsler. This becomes particularly clear with the introduction of laboratory porcelain into household porcelain, whose simple forms appear, for example, in the designs of Marguerite Friedlaender. Design in the post-war period followed on from modernism, while so-called “good form” continued to embrace a no-frills approach.

The topic Shaping a brand image presents well-known companies with a long tradition such as Pelikan, Olivetti and Pirelli as advertising clients who have initiated many creative collaborations. Known for its typewriters, the Italian manufacturer Olivetti worked for a long time with in-house designers, setting up a large advertising department that created a uniform corporate identity for its ad campaigns and packaging design. In the 1950s, the industrial designer Marcello Nizzoli and the graphic artist Giovanni Pintori in particular left their mark on the brand. The contemporary architecture of the production facilities and the furnishings of the Olivetti stores tied in with the corporate image.

The chapter Politics and provocation as an advertising strategy examines advertising that deliberately provokes with its content or messages, and which takes a stand on issues. Doyle Dane Bernbach’s campaign for the Jewish food company Levy’s (1967) from New York, which focused on diversity, is a good example, as are the controversial Benetton campaigns conceived by photographer Oliviero Toscani, which provided food for thought in the 1980s and 90s by addressing topics such as environmental protection, racism and HIV.

In the subject area Artists working commercially, the focus is on artists' reciprocal interests in terms of design. The exhibits illustrate for example the collaboration between fashion designer Martin Margiela and artist Marina Faust, as well as cooperative projects between the JW Anderson label and ceramicists Magdalene Odundo and Shawanda Corbett and influential photographer Juergen Teller. The mutual inspiration and appreciation is clearer than in any other subject area.

The chapter Dialogues looks at long-standing collaborations between

creative professionals, many of them based on personal ties and

shared interests. For eleven years, fashion designer Issey Miyake and

photographer Irving Penn worked together in a silent dialogue involving

intensive exchanges. Issey Miyake expressed his admiration for Penn

ever since his studies using the Japanese expression A un, which

means “two people breathing together”. Both were interested in a

materiality that works with an aesthetic of simplicity and is directed

against conventional ideas of luxury and status, among other things.

Geometric forms were just as decisive for Miyake’s cuts as they were

for Penn’s pictorial compositions.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, designers increasingly placed themselves at centre stage, many developing into the stars of the advertising campaigns they devised. The company Rasch Tapeten, for example, dispensed with any images of the product and instead posed prominent architects and designers with their furniture in front of a white wall, with the slogan “What’s missing is Rasch wallpaper”.

The section New tools, new photographers examines current trends in staging that are omnipresent in social media channels such as Instagram. Here, advertisers rely on influencers’ “street credibility” to lend product staging ostensibly democratic features. With Mayday (1999), for example, product designer Konstantin Grcic created a multifunctional lamp that can be found in many homes today. While the manufacturer Flos staged the lamp in front of an extracted background, the journalist Jasmin Jouhar gives Mayday a more personal spin by assembling photos of the lamp in private homes and offices.