I've known Boaventura de Sousa Santos for 20 years, and he has always had a friendly, helpful, and attentive demeanour towards people. In his lectures, which were always brilliant and eloquent, he left the huge audience interested and wanting to hear more and more from him. After his lectures, regardless of the size of the audience, he always made himself available to anyone who wanted to contact him, whether for autographs on his books or for photographs. In the postgraduate classroom, he encouraged all his students to be scientific, questioning, and open to dialogue. As a colleague, he always encouraged research and was open to discussing the underlying aspects of scientific work.

Since then, I've been studying and following the intellectual output of Boaventura de Sousa Santos, whose main characteristic is his distinctive thinking, which manages to make knowledge and social practices visible, explain, and analyse them without subalternizing them, especially those produced in the global South, within the framework of a new scientific paradigm, which includes the social and the political.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos is a prestigious social scientist who is internationally recognised, in addition to Portugal, at universities in Brazil and all other Latin American countries, as well as in various other countries and continents. In this sense, he has been recognised by public and private universities through the award of high academic titles, such as the more than 20 honorary doctorates he has received in Brazil and in several other countries around the world.

His work, as well as taking a broad and articulated approach to the production of knowledge on a variety of societal dimensions, is extensive and requires the scholarly reader to delve into his sophisticated, ground-breaking rationality, which devours hegemonic concepts while at the same time proposing to look at the world through new lenses and new categories. Therefore, in order to understand Boaventura de Sousa Santos' theoretical thinking, it is first of all necessary to be willing, along with him, to break with or at least be suspicious of everything that is apparently safe in the realm of science.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Boaventura de Sousa Santos focused on the issues of citizenship, science, modes of production of social power, analysis of Portuguese society, and globalisation. On these last two themes, he developed research projects that brought together dozens of researchers from six countries and resulted in the publication of two collections, one with five books and the other with eight books. The themes analysed in this period fall into various dimensions, as he himself explains, such as epistemology (A Discourse on Science, 1988 or Introduction to Post-Modern Science, 1989) and a scientific paradigm that is also a social paradigm, since it arises in a society that is itself revolutionised by science (A Discourse on Science, 1988).

In this latest book, with 13 editions published, Boaventura de Sousa Santos proposes a broadening and renewal of science, arguing for four axes of the emerging paradigm. Of these, two are very close to my heart, although it's not possible to think of this paradigm in halves. But these two have a direct link to the studies I carry out, because I always start from them in my investigations, both in the sense of recognising that "all knowledge is self-knowledge," and therefore the fallacy of neutrality is perceived as a fragile argument since it is not possible to remove the interest in studying issues that also affect us. It also states that all knowledge is local and total, re-signifying the place of production of knowledge about local experiences, showing its character of totality, as well as assuming that knowledge hierarchically assumed to be total has its origins in local thoughts and realities. This perspective qualifies the importance of studying local problems by recognising their universal dimension.

In the political and cultural dimension, he has the work "By the Hand of Alice: The Social and the Political in Post-Modernity" (1994). In this work, among many important concepts, epistemicide is undoubtedly the one that best expresses the idea of the process of creative destruction of knowledge and cultures not assimilated by white or Western culture, promoted by modern science in defence of its privileged status in essence.

In the 2000s, he went even deeper into his reflections, making them more robust, when he published the award-winning book A Crítica da Razão Indolente1: contra o desperdício da experiência (2000), which deals with science, law, and politics. In these three fields, Boaventura de Sousa Santos criticises the dominant epistemological crisis, opening up new possibilities for understanding within an emerging paradigm. This work contributes to a differentiated approach to scientific research that articulates or deals with science, law, and politics in isolation.

In addition to this, in the following years he published Grammar of Time (2006), which brings together articles from over a decade that were published as an integral part of a work that was published in pieces so as not to lose the temporality of the reflection, insofar as it advanced important texts to substantiate the framework of his theoretical production. This work, made up of thirteen chapters (articles) with themes that reflect the complexity of the time being analysed, mainly instigated me with three articles. The first is the sociology of absences and emergencies, which is an exceptional proposal to break with the invisibility of social experiences as well as point the way to unveil what is to come, the not-yet.

The Sociology of Absence and Emergence (2002) are two vigorous concepts from the work of Boaventura de Sousa Santos, originally published in an article in English. In his terms, the Sociology of Absences (2002) seeks to demonstrate that what doesn't exist is, in fact, actively produced as non-existent, as a non-credible alternative to what does exist. The question of non-existence then centres on a produced invisibility, a discreditability constructed in such a way as to point to scenarios without alternatives. At the centre of this framework, the Sociology of Absences seeks to transform impossible objects into possible ones and, on this basis, transform absences into presences. The Sociology of Emergencies (2002) consists, as Boaventura de Sousa Santos says, of carrying out a symbolic expansion of knowledge, practices, and agents in order to identify in them the tendencies of the future (the not-yet) on which it is possible to act in order to maximise the probability of hope in relation to the probability of frustration. From this perspective, Santos defines the sociology of emergencies as acting on both possibilities (potentiality) and capacities (potency). The not-yet makes sense (as a possibility), but it has no direction since it can end in either hope or disaster.

In particular, I consider the sociology of absences to be an innovative theoretical concept because, as well as breaking with the discredit produced to make subalternized social experiences invisible, it also points to the five social fields or types of experience—knowledge, development, work, and production; recognition; democracy; and communication and information—where these experiences can break with the idea of absence from reality or emerge in another mode of visibility.

Another article in "The Grammar of Time" that I consider very relevant is the Ecology of Knowledges, which was born out of the theoretical development of the sociology of absences and is an ecology that breaks with the monoculture of knowledge. This category is gaining a lot of importance and visibility in studies and research that analyse different types of knowledge outside the dominant axis of scientific knowledge. In Brazil, it has been widely used to subsidise studies into the know-how of the most diverse social groups and areas of knowledge.

Still in Grammar of Time, another important concept in the chapter "A multicultural conception of human rights" is diatopic hermeneutics, an important concept from the 1990s. According to Santos (1997), it is based on the idea that all cultures are incomplete and can therefore be enriched by dialogue and confrontation with other cultures. According to Santos, this incompleteness is not visible from within the culture since the aspiration to totality leads to the part being taken for the whole. Thus, he subscribes that the aim of diatopic hermeneutics is not to achieve completeness—an unattainable goal—but, on the contrary, to broaden awareness of mutual incompleteness as much as possible through a dialogue that takes place, as it were, with one foot in one culture and the other in another. He concludes by saying that this is what makes it diatopic. This theoretical concept becomes fundamental in the study of experiences between different cultures, which cannot be placed in political disputes but can be dialogued within the limits of what is understandable in different cultural ways of being, acting, and producing knowledge while respecting what cannot be negotiated.

And the last three works, which I greatly appreciate and are valuable for research in various areas of knowledge, such as sociology, anthropology, education, human rights, and social work, among others, are the Epistemologies of the South, which, according to Santos (2018), are outlined in a theoretical, methodological, and pedagogical universe that challenges the dominance of Eurocentric thought and are theorised in three main works: "Epistemology of the South" (2010), "The End of the Cognitive Empire" (2018), and the newest, "Knowledge Born in Struggle: Building the Epistemologies of the South" (2024).

As I see it, the entire theoretical framework produced by Boaventura de Sousa Santos is gradually taking shape and creating a solid foundation for the concept of Epistemologies of the South, which creates an amalgam between bodies, knowledge, and corazonar, as a feeling-thinking that expresses itself in all the knowledge produced within subalternised social experiences, because for Santos, "'Corazoning' is the act of building bridges between emotions or affections on the one hand and knowledge or reason on the other" (Santos, 2018).

Without exhausting the creative and profound potential of his work, Epistemologies of the South (2010) is one of his most widely used theoretical frameworks. According to Boaventura de Sousa Santos, an epistemology of the South is based on three orientations: learning that the South exists; learning to go to the South; and learning from the South and with the South. His reflection on the epistemology of the South began in 1995, when he proposed this concept, and since then he has been deepening it based on his realisation that the vast field of questions covered by philosophical reflection far exceeds modern rationality, with its areas of light and shadow, its strengths and weaknesses.

In these terms, over the last twenty years he has been working extensively on this concept in research both in the Global South and in Europe, such as the project "Alice, Strange Mirrors, Unexpected Lessons" (2011–2016), funded by the European Research Council as lead researcher.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos, in his vast scientific work, has created several theoretical concepts, in addition to the ones I have presented, which have underpinned studies in different areas of knowledge. This robust theoretical framework, produced by him, has served as a reference in scientific research in postgraduate programmes in Brazil and abroad.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos' work has been used as a consistent and appropriate theoretical framework in the scientific production of the theses and dissertations carried out within the scope of these programmes, in their master's and doctoral courses, as well as for research projects funded by national and international funding institutions.

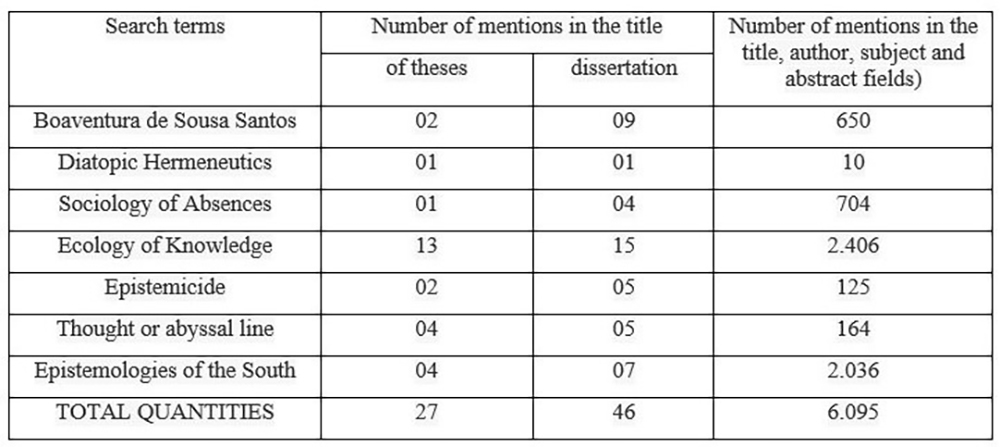

In Brazil, his work has served as the theoretical basis for a significant number of master's dissertations and doctoral theses at various Brazilian universities. Thus, in a survey carried out in the database of the Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (BDTD) of the Brazilian Institute of Information in Science and Technology (IBICT)2 , we gathered the following data:

The influence of Boaventura de Sousa Santos' theoretical production on Brazilian scientific production at postgraduate level.

Source: IBICT data, collected on 06/June/2024.

Source: IBICT data, collected on 06/June/2024.

This shows the confidence of thousands of Brazilian scientists and researchers in the scientific quality of the theoretical framework produced by Boaventura de Sousa Santos. This figure of more than 6,000 theses and dissertations is broken down into a much higher number of scientific articles presented at scientific events and published in journals in Brazil and other countries.

In addition, in the context of postgraduate programmes in Brazil, there is also a large number of bibliographical references to Boaventura de Sousa Santos in the subjects taught by Brazilian postgraduate lecturers in the social sciences and humanities.

In short, Boaventura's work, from the outset, is centrally concerned with the idea of cognitive justice, as a way of re-signifying the knowledge produced in subalternised social experiences.

Notes

1 Jabuti Prize in 2001. This annual Brazilian award is the most traditional literary prize in Brazil, awarded by the Brazilian Book Chamber, created in 1959.

2 Launched in 2002.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa and MENESES, Maria Paula (eds). Knowledge born in struggle: building epistemologies of the South. Coimbra: Edições 70, 2024.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. The Critique of Indolent Reason: Against the Waste of Experience. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. The grammar of time. Towards a new political culture. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Introduction to a Post-Modern Science. Porto: Afrontamento, 1989.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. The end of the cognitive empire. The affirmation of southern epistemologies. Coimbra: Almedina, 2019.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Towards a sociology of absences and a sociology of emergencies. In: Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais. nº 63, October, p: 237 - 280. Coimbra: CES, 2002.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Alice's Hand: The Social and the Political in Post-Modernity. Porto: Afrontamento,1994.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. A Discourse on the Sciences. Porto: Afrontamento, 1988.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. A multicultural conception of human rights. In: Lua nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, São Paulo, v. 39, p. 105-124,1997.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa; Meneses, Maria Paula (eds.). Epistemologies of the South. Coimbra: Almedina, 2009.