A minority of the world‘s population appears to be misogynistic and continues to oppose efforts to achieve gender equality and empower women and girls. The misogynistic minority cannot be permitted to undermine gender equality policies supported by large majorities of the public worldwide.

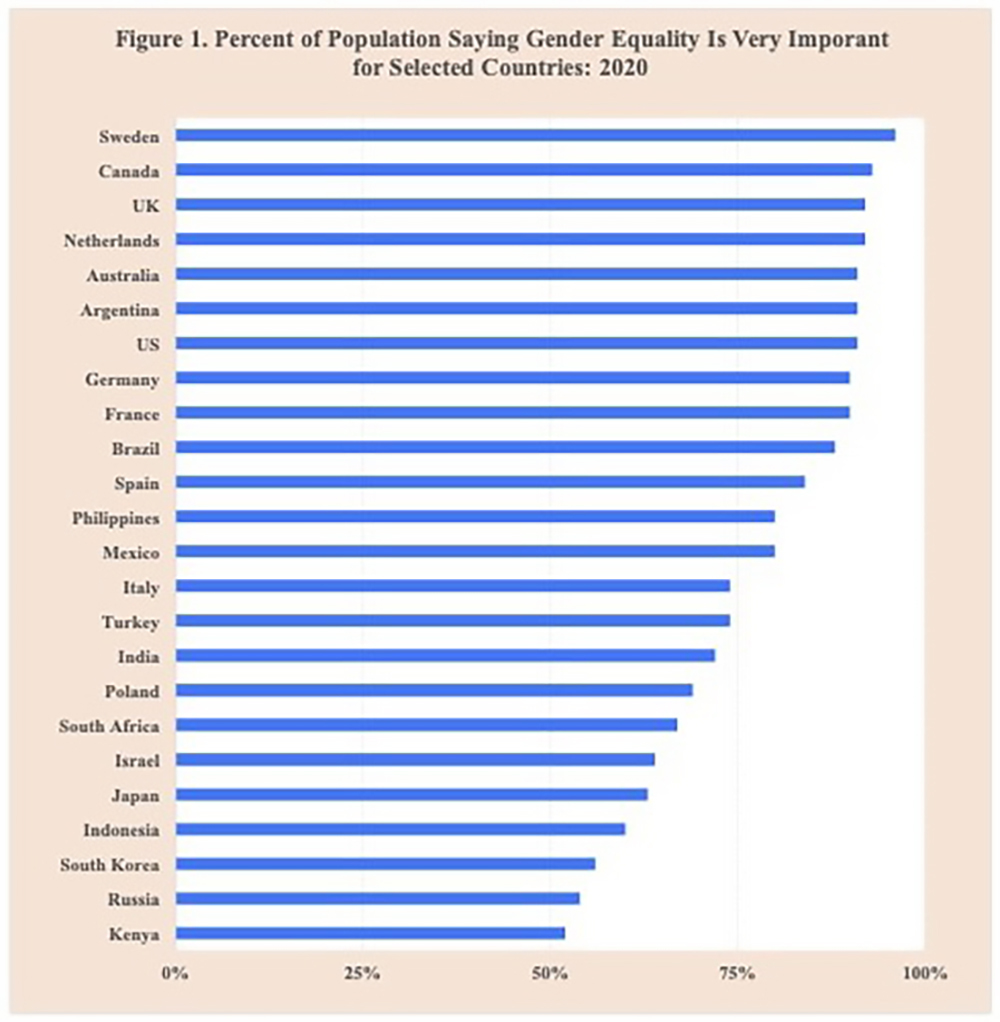

National surveys across different regions of the world find large majorities of the public supporting gender equality and saying it is very important for women in their country to have the same rights as men. The majorities supporting gender equality vary from highs of 90 percent or more in countries such as Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom to lows of approximately 55 percent in Kenya, Russia, and South Korea (Figure 1).

Among the misogynistic minority, too many consider women inferior to men, treat them as their personal property, deny them control over their lives and bodies, restrict their political, social, and economic rights, and too often ridicule, intimidate, and physically abuse them.

The misogynists also generally dismiss the fundamental principles of equality of men and women enshrined in international documents, treaties, declarations, and instruments, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the UN Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

Misogynists also tend to oppose the gender equality laws and policies that are incorporated in many regional treaties and national instruments.

The current struggle for gender equality follows a lengthy history of oppression of women through men’s use of authority, law, physical force, and violence. In many societies around the world, women and girls have been unjustly held back from achieving full equality and enjoying their basic human rights.

Throughout the ancient and medieval worlds and continuing into much of the modern era, women did not have the same legal, economic, and political rights as men. In ancient Greece, for example, women lacked fundamental rights, including property ownership and participation in the political system.

Moreover, in nearly all societies in the past, women were under the control of their fathers and husbands and held back from making personal decisions and achieving equality with men. In general, women had few options or choices for supporting themselves outside of marriage and were wed or forced to marry, typically at relatively young ages, with the primary aims being to provide sexual relations, bear children, and maintain or work in a family household.

It was only around the beginning of the 20th century that countries began passing legislation ensuring women the right to vote and stand for election. The first country to permit women to vote was New Zealand in 1893. About a decade later, it was followed by Australia, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland.

A couple of decades later, women were granted the right to vote in the United States and the United Kingdom. Approximately a century later, the most recent countries allowing women to participate in elections are Bhutan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

By around the middle of the 20th century, more than half of all countries had granted women the right to vote, although some initially had restrictions for women of certain backgrounds based on age, education, marital status, or race. Today, none of the world’s nearly 200 countries bar women from voting because of their sex (Figure 2).

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Various organizations have compiled rankings and indexes indicating the standing of countries on gender equality and the rights and well-being of women. Among the countries with some of the highest ratings on gender equality and the basic rights of women are Denmark, Finland, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Sweden.

In contrast, some of the countries with the lowest ratings on women’s rights and equality also typically suffer from civil conflict, which undermines efforts aimed at gender equality and the well-being of women. Among those countries are Afghanistan, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.

Particularly noteworthy is the dire situation of gender equality in Afghanistan. It is the only country in the world with bans on female education and employment.

Sociocultural factors, traditional practices, and beliefs in Afghanistan have contributed to the country’s dire situation of gender equality in both education and employment. Girls are banned from attending secondary school, and women’s employment is all but prohibited, with the exceptions being in the areas of health and education.

In addition to differences among countries, significant differences in gender equality and the status of women can also vary within countries. In the United States, for example, some of the states that have attained the highest levels of women’s well-being, health, and safety are Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Some of the states at the other end of the ranking are Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

Although women make up 50 percent of the world’s population of 8 billion, their representation among governments and participation in politics is considerably less. At all levels of decision-making and policy formulation, especially in the areas of defense and the economy, women are underrepresented. For example, worldwide, women make up approximately 25 percent of members of parliament and cabinet ministers and serve as heads of state or government in about 15 percent of countries.

The education of girls and women is widely recognized to be one of the world’s best investments, providing a basic foundation for a lifetime of learning and advancing and empowering girls and women in their personal lives, homes, careers, communities, and countries.

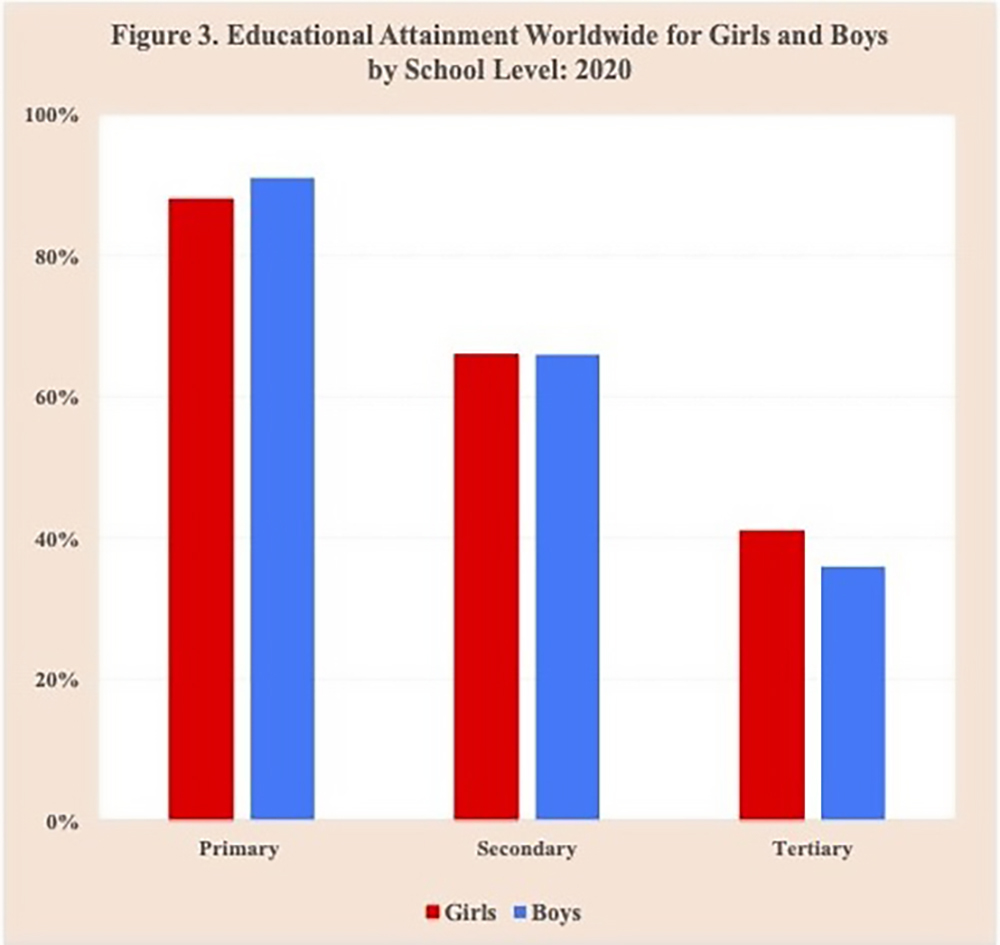

During the recent past, considerable progress has been achieved in the education of girls and women. Worldwide, the rates of school enrollment at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels are getting closer to equal for girls and boys (Figure 3).

Source: Global Gender Gap Report.

Source: Global Gender Gap Report.

About two-thirds of all countries have reached gender parity in primary school enrollment. However, the completion rates in many developing countries, especially in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, are lower for girls than boys. In addition, globally, an estimated 129 million girls—32 million at the primary level and 97 million at the secondary level—are not in school.

At the tertiary educational level, women’s enrollment has increased considerably, with female students outnumbering male students. However, female students are heavily enrolled in the arts, social sciences, and humanities rather than undertaking science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degrees. Also, the relatively high enrollment of women in the student population does not translate into their presence in university leadership positions, as less than 40 percent of university professionals are women.

With respect to participation in the formal labor force, a considerable gender gap exists, with the rates for men and women being approximately 75 and 50 percent, respectively. However, most of the work done by women outside the formal labor force globally is unpaid.

The large majority of women, approximately 70 percent, would prefer to work in paid jobs. However, a persistent set of traditional biases, stereotypes, and socio-economic barriers keep many of them out of the workforce.

The level of female participation in the labor force varies considerably across regions. While in most regions more than half of all women aged 15–64 participate in the labor market, only a quarter or less do so in the regions of South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. The levels of female labor force participation are also generally high in the poorest regions, where agriculture is the dominant sector, with women frequently involved in small-holder agricultural work.

Women are also more likely to spend double the amount of time than men on caregiving, tackling domestic chores, and doing housework. Among children aged 5 to 14 years, girls also spend considerably more time than boys on unpaid household chores.

Another major development that has influenced gender equality considerably was the introduction of women’s modern methods of contraception beginning in the 1960s. Those methods, especially oral contraceptive pills, intrauterine devices, and implants, permitted women to choose the number, timing, and spacing of their births.

That ability in turn reduced the fear of unintended pregnancy, reduced the incidence of abortion, and provided women with control over their reproductive lives similar to those of men. Such control improved the health of women and their offspring, contributed to their overall well-being, and allowed them to attain their desired number and spacing of children.

In addition, women’s control over their reproduction also permitted them to pursue higher education, careers, employment, recreation, travel, decide on lifestyles of their choice, and participate more fully in society.

Notable progress on the equality of women and men has been made during the recent past. However, the world is not on track to realize Goal 5 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls by 2030.

At the current rate of progress, it is estimated that it will take hundreds of decades to achieve gender equality, in particular closing gaps in legal protection, removing discriminatory laws, equal representation in leadership in the workplace, and ending child marriage. Reducing that lengthy time frame will require making investments in policies and programs aimed at accelerating the progress to achieve gender equality.

In addition to those investments, the basic rights of women need to be protected and enforced, practices that oppress women are removed, and the personal decisions and life choices of women recognized and promoted.

Also importantly, the attitudes, objections, and behavior of the world’s misogynist minority cannot be permitted to undermine gender equality policies and practices called for and supported by large majorities of the public worldwide.