The "Beyond Growth 2023 Conference" was organized by the European Parliament and numerous supporting organizations from May 15 to 17 in Brussels. The aim of this conference, according to the organizers, was to challenge the conventional policymaking approach within the European Union and redefine societal goals to move beyond the sole focus on economic growth measured by GDP. The goal was to establish a post-growth, future-fit EU that integrates social well-being, sustainable economic development, and respect for planetary boundaries. Often referred to as the "Woodstock of Post-Growth," this historic event was attended by distinguished scholars, including Nobel Laureates, prominent politicians such as Roberta Metsola, President of the European Parliament, and Ursula Van der Leyen, President of the European Commission, as well as numerous activists and representatives from supporting organizations.

During the conference discussion, it became evident that the work of Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics, played a pivotal role in understanding the future of economic growth. I aim to highlight two key concepts of her work. In next month’s article, I intend to provide a report on Earth for All, a report to the Club of Rome presented on the 50th anniversary of Limits to Growth, which is essential for comprehending the principles of post-growth economics.

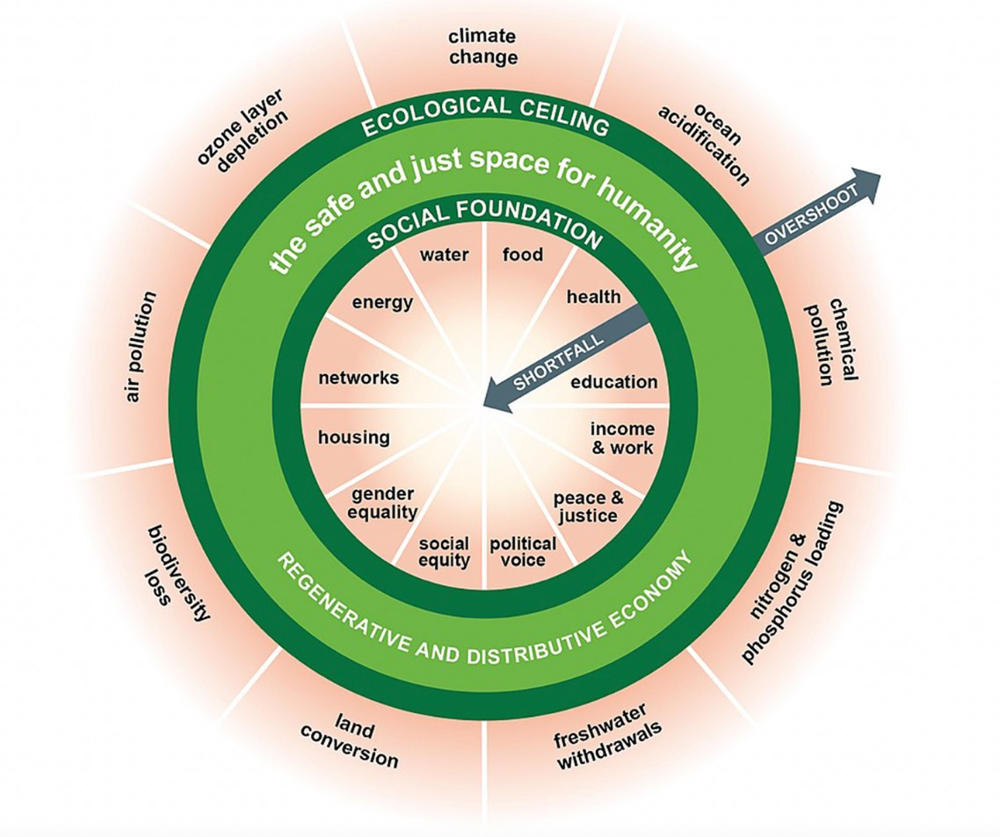

Kate Raworth's work involves a critical examination of the origins of economics and puts forth the concept of a "doughnut" framework, which defines the ideal operating space for economics in terms of societal safety and justice. The doughnut view offers a visual guide for 21st-century economic thinking. According to Raworth, the economy should operate within the space delineated by the outer ring of the doughnut, representing the ecological ceiling, and the inner circle, which represents the acceptable social foundation. This framework ensures a balance between environmental sustainability and meeting societal needs, as depicted below.

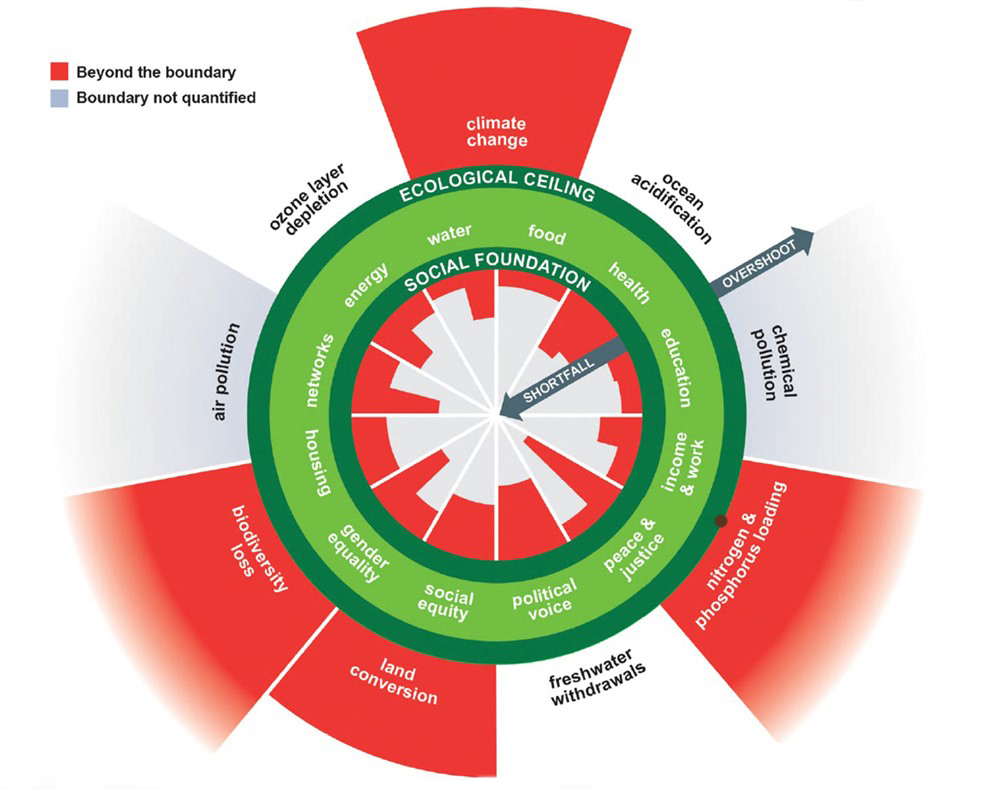

Raworth employs scientific targets to quantify the ecological boundaries within the doughnut framework. For instance, she sets the planetary boundary for climate change at 350 parts per million (ppm) of atmospheric CO2, which is considered acceptable. However, with current levels exceeding 400 ppm, the representation of the global doughnut using data (as depicted in the following diagram) would indicate a significant ecological overshoot.

In addition to ecological indicators, Raworth also proposes social indicators to gauge societal well-being. As an example, her social indicator for world food is the percentage of malnourished individuals, which currently stands at 11% (representing a shortfall). The boundary for this indicator is set at 0%, indicating a just and equitable state. The specific data used for global analysis can be found in the appendix of Raworth's book, "Doughnut Economics," and is visualized in the accompanying doughnut diagram.

It is obvious that the world economy is currently facing significant challenges, as indicated by ecological overshoots in various areas such as climate change, biodiversity loss, land conversion, and nitrogen and phosphorus loading. Indeed, all the social factors are currently falling short of desired targets.

Naturally, the doughnut framework can be customized and applied to different regions, cities, and countries. The considerable activity at the Doughnut Economics Action Lab illustrates the concept's usefulness. The method is agnostic with respect to economic growth in that some areas may need to grow, such as activities in developing nations, whereas fossil fuel production should decline to respect ecological limits.

Raworth provides clarification on the gradual loss of the original goal of economics. In Greece, Xenophon first used the term "the art of household management." Subsequently, Aristotle differentiated economics from chrematistics, the art of acquiring wealth. Two thousand years later, with Isaac Newton's discovery of the laws of motion, the allure of scientific status was such that James Steuart proposed political economy as "the science of domestic policy in free nations." Nonetheless, he spelled out the purpose of economics. "The principal object of this science is to secure a certain fund of subsistence for all the inhabitants, to obviate every circumstance which may render it precarious, to provide everything necessary for supplying the wants of the society, and to employ the inhabitants (supposing they to be free-men) in such a manner as to naturally create reciprocal relations and dependencies between them, to make their several interests lead them to supply one another with their reciprocal wants1."

Ten years later, Adam Smith followed in Steuart’s lead, considering political economy to be goal-oriented: It had ‘'two distinct objects: to supply a plentiful revenue or subsistence for the people, or, more properly, to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and secondly, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for the public services2."

Seventy years later, John Stuart Mill began the tendency to turn away from the description of the purpose of economics, focusing instead on the discovery of its apparent laws. In 1932, Lionel Robins declared that ''Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means that have alternative uses 3." The goals of human behavior are not questioned. Furthermore, economists choose to adopt a theory of behavior, the rational economic man, that is far from the complete study of humans.

This is further complicated by the concept of utility, defined as the satisfaction gained from consuming a bundle of goods, without considering that billions of people lack the means to fulfill their needs and desires, and that many valuable things are not available for purchase. It is assumed that the price people are willing to pay for a good is a sufficient measure of its utility. "Adding to this is the seemingly reasonable assumption that consumers always prefer more to less, which leads to the conclusion that continuous income growth (and consequently, output growth) is a reliable indicator of continuously improving human welfare4."

Continual output and income growth, excluding ecological impacts and the original purpose of economics, are the guiding principles of traditional economics. It is flawed yet profitable and, with the help of Big Oil, has brought us the devastation of the planet in terms of climate change, biodiversity, land conversion, and nitrogen loading. As Raworth points out, "our beliefs about economic growth are almost religious: personal in nature, political in consequence, privately held, and little discussed5." Politicians adore growth because it apparently solves so many of their problems, at least in the short term.

The problem is that we have ignored the longer-term issues, particularly those concerning the environment and inequality. Raworth presents the growth perspectives in the following graph, where the amount of decoupling of resource use (less resource needed for the production of the same activity or product) is compared to GDP.

The challenge is that if GDP is to continue growing, particularly in high-income countries with high resource use, the associated resource use must not only decrease relatively and absolutely, but also decouple absolutely and sufficiently to remain within planetary boundaries. The debate on growth revolves around the extent of decoupling that is achievable and the new policies needed to promote benefits that are important to us but are less material (and often not reflected in the GDP measure). These policies will be discussed in subsequent articles.

References

1 An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy, (2017), Doughnut Economics, Random House. Kindle Edition, Ch. 1, Steuart, J. (1767).

2 Raworth, K., 2017, Doughnut Economics, Random House. Kindle Edition, Ch. 1, Smith, A. (1776) An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book 4.

3 Raworth, K., 2017, Doughnut Economics, Random House. Kindle Edition, Ch. 1, Robbins, L.

(1932) Essay on The Nature and Significance of Economic Science. London: Macmillan.

4 Raworth, K., 2017, Doughnut Economics, Random House. Kindle Edition, Ch. 1.

5 Raworth, K., 2017, Doughnut Economics, Random House. Kindle Edition, Ch. 7.