Research in recent years has enabled us to understand the global power structure that emerges from the digital revolution, with online global control, and radically new capacity to reach every country and every individual in this global web.

The world Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where the species is known to gather annually to cleanse its reputation.

(Peter S. Goodman – The Davos Man, 2024)

These neoliberal states have opened up each national territory to transnational corporate plunder of resources, labor and markets.

(William I. Robinson, 2016)

Our daily economic activities are usually pretty down to earth. The pharmacy, the shops, the supermarket, the bus, eventually an Uber, the gas station, taking the kids to school, and so on. Looks pretty local. But looking up, instead of obeying the film Don’t Look Up, is precisely what is necessary if we want to understand why the prices have gone up, why there is so much plastic, and why there is ultra-processed food on every supermarket shelf. We know it’s all bad, and the shops know it too, and we are supposed to have regulations for all this – yet it is there, and growing. In fact, who’s in charge?

Ultimately, lots of researchers have looked up and gradually brought light to the mess we have up there, and the shapes are becoming distinct. A good starting point is the 2007 global financial crisis, which led the ETH, the main Swiss public research institute, to present in 2011 the first overall study on the network of global corporate control1. The results were impressive: 737 corporations run 80% of the global corporate world, 147 of which run 40%, and 70% of them are financial institutions. This is the top of the pyramid: mostly money management.

The governor of the Bank of England commented at the time that this study was changing our worldview on how the economy is working. The authors of the research commented in the paper that there was no way to avoid that we were facing “the rich club”. Equally impressive is the fact that, stressed by them, this was the first global study on corporate power, while the process had been going on for decades, basically since Margareth Thatcher and Ronald Reagan put themselves at the corporations’ service. There clearly was no interest in putting the lights on. But now we have a clearer picture.

The Vale corporation is a good example. It is a multinational corporation and the largest producer of iron ore and nickel in the world. According to Wikipedia, “it also produces manganese, ferroalloys, copper, bauxite, potash, kaolin, and cobalt, currently operating nine hydroelectricity plants, and a large network of railroads, ships and ports used to transport its products.” Total assets in 2021 amount to around $90 billion, owned by Ma’aden, Previ, BlackRock, and Mitsui & Co. It was a Brazilian state company, and at the time its profits enabled the state to finance different development projects, as was the case with the Petrobrás oil company. Presently, Vale basically exports Brazilian raw materials, generating dividends for international shareholders and their Brazilian helpers. It is a huge and diversified corporation that serves interests higher up.

Privatization is also de-nationalization and basically represents a drain on the country’s mineral riches. This leads to fragilizing public investment capacity in social policies like education, health, security, and other essential public services which represent the “indirect salaries” of the population, as well as the infrastructures such as energy, transportation, communications, and water/sewage complex, which are essential for the population but also for the productivity of the overall economy. It has become a drain, and the population and local businesses pay the price. Asset management corporations at the top earn more. This deepens the global divide.

The decision process is essential here, and it is what we can call corporate governance. The company is in Brazil, and the extracted materials are on the Brazilian territory, but the decision process has migrated to a few key shareholders like BlackRock, Vanguard, UBS, JP Morgan, and the like. They are the so-called absentee owners, and this has changed the overall governance system. Vale and its dependent company Samarco were aware they had to fix the dams that held the contaminated by-products, but the absentee owners decided raising dividends was more important. The result was the tragedy of Mariana and Brumadinho, huge dam bursts, loss of lives, and overall contamination. The shareholders of Vale, like the Saudi Arabian company Ma’aden, the American BlackRock, and the Japanese Mitsui had the upper hand, maximizing dividends in the short term.

An impressive set of lawsuits followed, and continue to this day; the companies will have to pay tens of billions, but are “negotiating”. Remember the BP Deep Horizon tragedy in the Gulf of Mexico? We now have the reports, and the same process was found. They had suspended maintenance to privilege dividends. And since the managers’ bonuses are linked to the dividends at the top, the decision process privileges money at the top, not the results at the bottom. It is as simple as that, and the fantastic growth of CEO salaries, from 20 to 300 times the average company salary over a few decades, is directly linked to the explosion of financial profits (rents, actually, since it’s not based on productive contribution) at the asset management level at the top and slow growth at the producers’ level.

It is difficult for people to imagine where the top is, or what it looks like. The Forbes Billionaires of the World 2024 edition shows the 2,781 world billionaires, sitting on an accumulated wealth of $14 trillion — more than half the GDP of the United States. Their wealth grew by 17% in 12 months. Since GDP growth was around 3%, we are facing net extraction by the happy few2. The main wealth accumulation process is only marginally based on productive investment, it is rather essentially based on financial investment. Just a small percentage of share control in the overall dispersed shareholder’s universe is sufficient to enforce control by the major asset management corporations.

In Titans of Capital (2024), Peter Phillips brings us the overall picture of the global governance system. “The global richest .05 percent represents 40 million people, including more than 36 million millionaires and 2,600 billionaires, who turn over their excess capital to investment management firms like BlackRock and JP Morgan Chase. The top ten of these firms together controlled close to $50 trillion in 2023. These firms are managed by the 117 people identified below. The top ten capital investment companies extensively cross-invest in each other. Cross-investments between the top ten firms amounted to $320 billion in 2022. Cross-investment practices imply a close monitoring of each other’s policies and a commonality of mutual interests in market maintenance and growth. The 117 Titans decide how and where global capital will be invested.3”

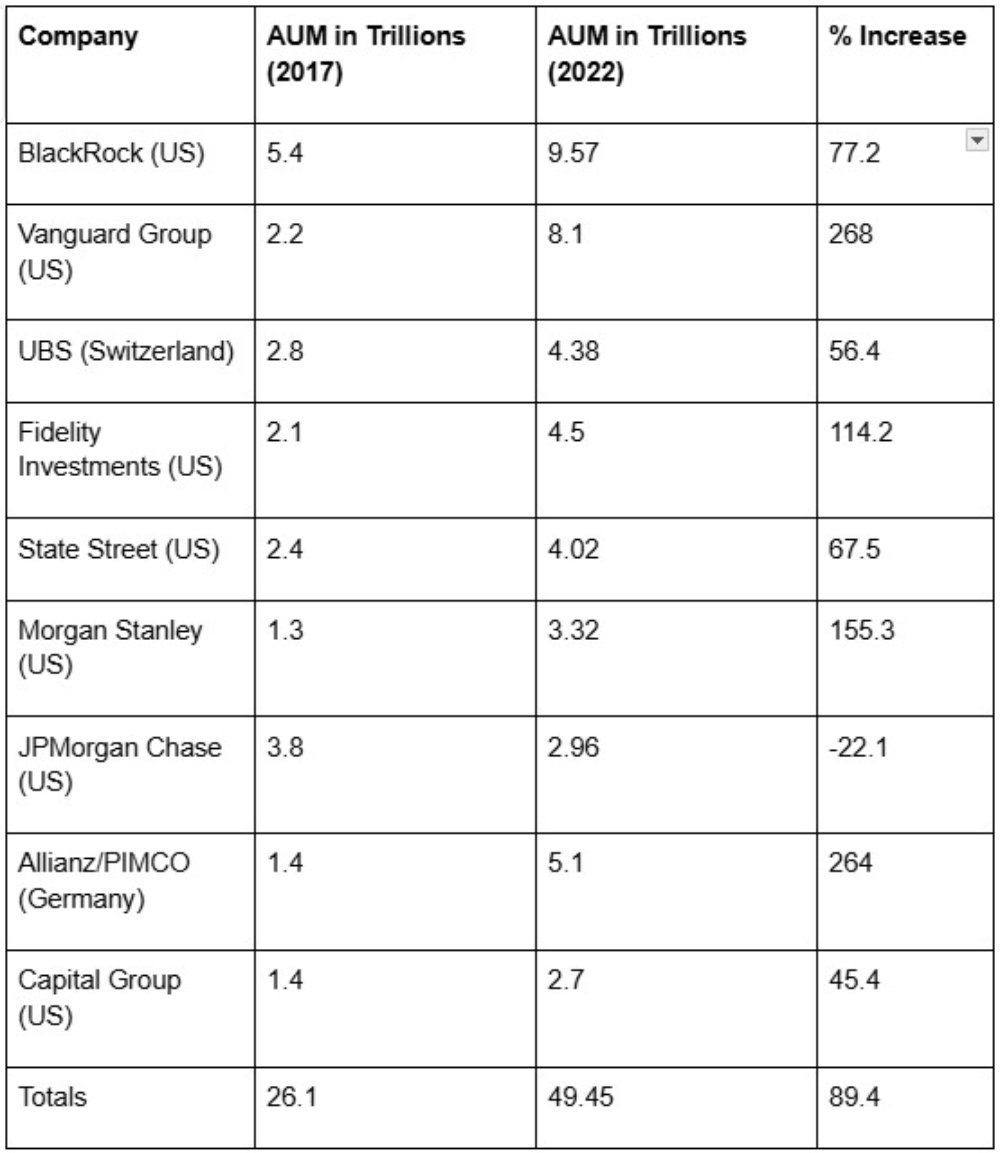

The top ten global capital investment companies - Changes in Assets under Management (AUM) from 2017 to 2022

Peter Phillips – Titans of Capital: how concentrated wealth threatens humanity – The Censored Press, Fair Oaks, Canada, 2024, p. 50

The figure shows that these ten corporations managed $26.1 trillion in 2017 and $49.5 trillion in 2022, an 89.4% growth in five years. This gives us not only the dimension of the concentration of economic power but also the level of acceleration. By focusing on what he calls the titans — the top managers of these 10 top corporate giants — Phillips brings a new approach, but closely converging with the Swiss research on the world corporate control network and the Forbes list of billionaires I mentioned above. We thus have the corporate control and the resulting wealth giants, and now proceed to the 117 directors of the 10 key corporations. “While it can be determined that there are thousands of people with personal holdings equal to or greater than the individual 117 Titans, what makes them significant is their responsibility for investment decisions of close to $50 trillion”.

“Sitting on the boards at the uppermost concentration of capital wealth in the global investment network, their decisions accelerate capital concentration, impact the environment, earn profits from regional and global wars, undermine democracies, and endanger socioeconomic stability for all.” These are the managers of the global system. Two-thirds of them are American. “They were born in the United States or Europe, raised in a wealthy, professional family, and attended an elite private university…They take seriously their fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns on the capital investments under their control.”

This has little to do with free market competition. Most of these directors simultaneously manage interests in similar corporations among the top ten, and Phillips presents their positions in 133 corporations out of this group. So, for example, BlackRock has 17 directors, with assets under management (AUM) of $9.5 trillion in 2022, and cross-investments in Vanguard, State Street, Capital Group, Fidelity Investments, and Morgan Stanley. Just as a reference of proportion, while in 2024 BlackRock directors manage over $10 trillion, Biden’s federal budget is around $6 trillion.

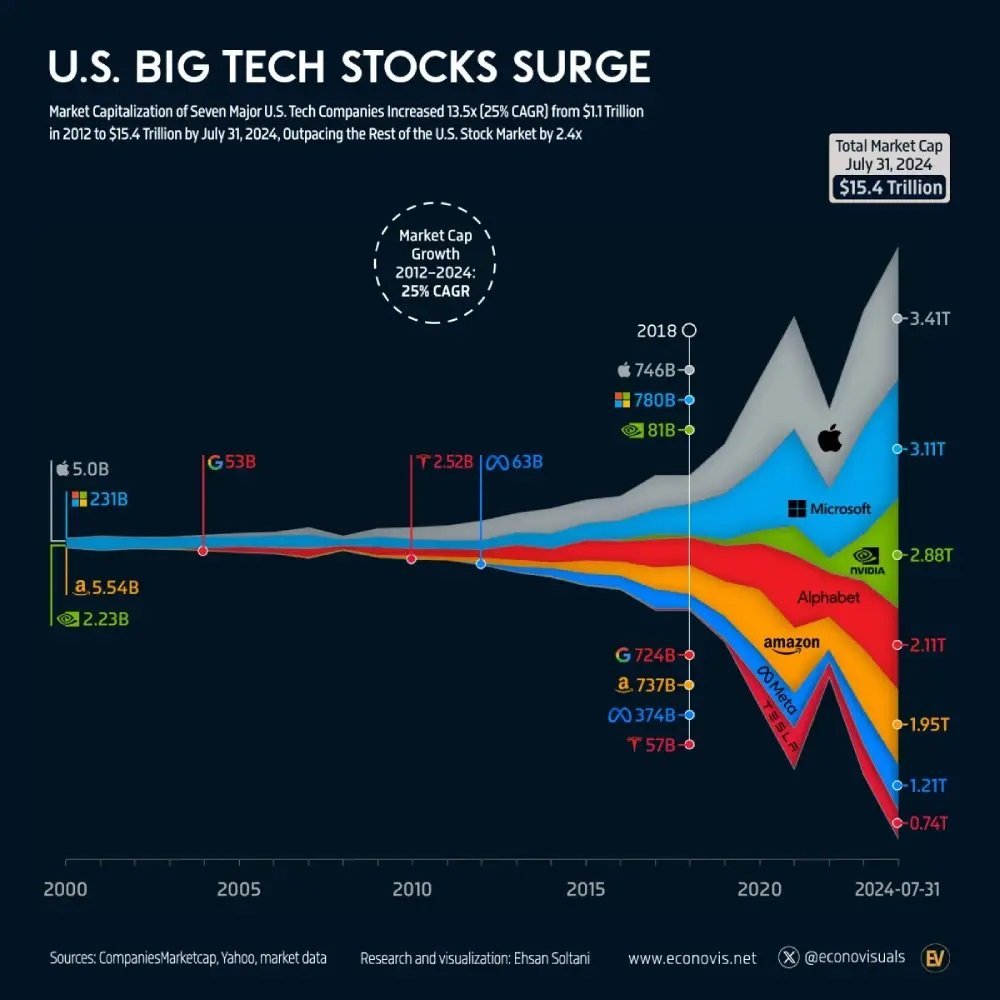

Most of these 10 top asset management corporations invest and exercise control in another group of giants, the 7 US tech companies4:

These converging interests of money managers and high-tech corporations that reach every one of us through different areas or intermediation, for purchases or in the attention industry — hours of our daily time — generate a new top-heavy control system, with extremely concentrated power, but also a global capillary network that reaches all of us. It controls the three elite policy councils (Council on Foreign Relations, Business Roundtable, and Business Council), exerts a key influence on the World Economic Forum, participates in the top intelligence and military institutions and military equipment-producing corporations; the top 10 oil and gas corporations; the top 6 coal producers; the top 5 tobacco corporations; the plastics, firearms, and gambling industries; and the booming private prisons system. Whatever makes big money.

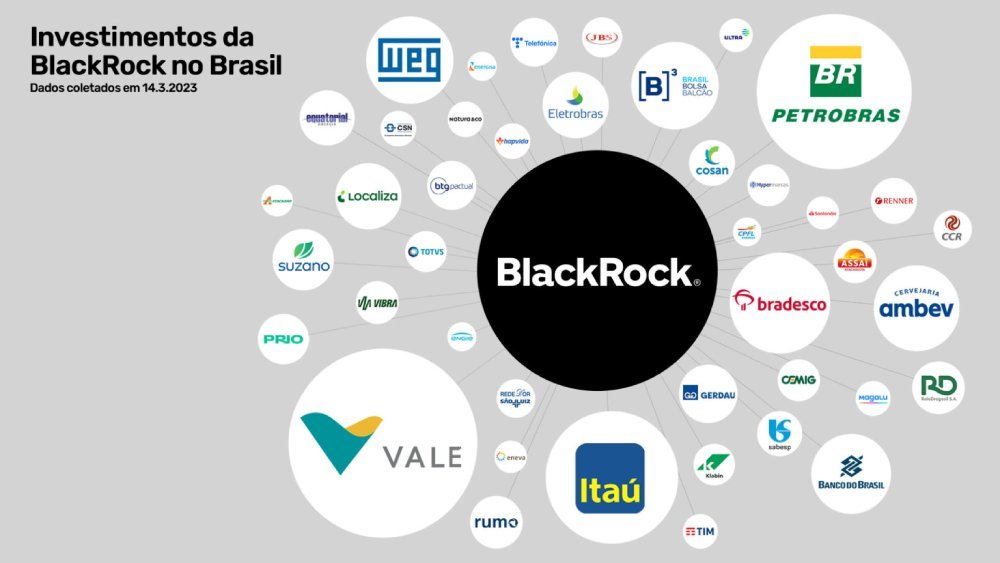

Going down the pyramid, we can see how these BlackRock directors will determine decisions in the Brazilian corporate world5:

We can see that BlackRock is in many areas of the Brazilian economy, but it is in so many countries as well. The common denominator in the decision process is short-term shareholder maximizing. This virtual money can reach, literarily, every pocket. The huge student debt throughout the world affects so many students, health debt has become a giant problem – particularly in the countries where health services have been privatized – and we all contribute segments of our expenditures in every area, paying through Visa for example, taking an Uber, or shopping on Amazon. Global inequality has become absurd, as documented in many reports. The environmental dramas are just as challenging. This study by Peter Phillips shows the Titans playing a key role in both processes.

Larry Fink, billionaire, and CEO of BlackRock, serves as a World Economic Forum trustee and keeps referring to ESGs and corporate responsibility. Jamie Dimon, chair of the Business Council and CEO of JP Morgan Chase, stresses that “these modernized principles reflect the business community’s unwavering commitment to pushing for an economy that serves all Americans.” According to Phillips, “the Davos Manifesto provides the Titans with a moral justification for continuing their path of wealth inequality while posturing as sensitive to human rights and environmental concerns.”

The concentration of economic, social, and political power on the planetary level has been accelerating in recent decades, as the technologies advance and power begets more power, allowing more concentration. We are facing a huge money-making power pyramid, devastating the world through inequality and environmental catastrophes, and breaking down any attempt at regulation.

Notes

1 S. Vitali et al., The network of global corporate control – ETH – 2011.

2 Forbes Brasil, year XI, n. 118, 2024.

3 Peter Phillips – Titans of Capital: how concentrated wealth threatens humanity – The Censored Press, New York, 2024.

4 US Big Stocks Surge – Visual Capitalist - The Surging Value of the Magnificent Seven.

5 João Peres - No Brasil, maior gestora de fundos do planeta tem investimento três vezes mais poluidor que na Europa e nos EUA – O Joio e o Trigo, 18 de maio de 2024.