American composer Igor Stravinsky said, “music is given to us specifically to make order of things, to move from an anarchic, individualistic state to a regulated, perfectly conscious one, which alone insures vitality and durability.”

His assertion seems particularly germane for young people because a child’s brain is in the most rapid period of neural development. During the mid-childhood years, the brain starts to make connections, accentuating the most important ones. This becomes the basis for human understanding of music, and ultimately the basis for what we like in music, what moves us, and how it moves us. Early childhood and adolescence are, in short, an ideal time for educators to implement music to prime students for more complex facts and concepts to be presented later in the child’s educational odyssey.

The learning benefits attributed to music include relaxation and stress reduction, the fostering of creativity through brain-wave activation, the stimulation of imagination and thinking, the stimulation of motor skills, speaking and vocabulary, a reduction in discipline problems, the focusing and alignment of group energy, and as a vehicle for conscious and subconscious information transmission.

In Out of Our Minds: Learning to be Creative, Ken Robinson points out that the power and effect of music seems to be particularly active in the cerebellum. The cerebellum is, evolutionarily speaking, the oldest part of the human mind. “It (the primitive brain) is a set of pre-programmed regulators that keep the body running and reacting in ways that ensure survival.”

Eric Jensen argues in Brain-based Learning: The New Science of Teaching and Training that the cerebellum is particularly ignited by eurhythmics. “Music may be a universal form of communication that has influenced species preservation and played a role in mate attraction, bonding, and harmony.”

Daniel Levitin argues in This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession, that music is not merely a social conduit or a didactic tool, music seems to be biologically coded into human DNA as a means of communicating, adapting and surviving.

“Musical activity involves nearly every region of the brain that we know about, and nearly every neural subsystem,” Steven Pinker, author of How The Mind Works, said. “Language is clearly an evolutionary adaptation.” His book explains and synthesizes the major principles of cognitive science. A large portion of his thesis argues that it is necessary and proper that music play a larger role in academia because music, a universal language system, is a biological function of human adaptation and evolution.

Modern schooling is, Howard Gardner argues, antiquated primarily because it fosters, foments, and cultivates merely linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligence in students, yet fails to foster various other intelligences. This antiquation gradually diminishes problem-solving skills in students because the world presents humanity with new problems each day, but schools fail to keep pace with the rate the world outside of academe evolves.

Music, however, has transcendent power. It has the potential to incite, excite, and ignite various intelligences. The reason music might be an excellent promoter of mental flexibility is that it is not inherently about anything, the way language is. Therefore, music is an incredibly pliant didactic tool. Music can be transformed and adapted in an infinite number of ways.

Jules Combarieu said, “music is the art of thinking.” Therefore, the importance of melding music and academe to the fullest seems particularly prudent in the wider context of a Digital Age.

In Wired Magazine’s inaugural issue (1993) an article written by Lewis J. Perelman, titled “School’s Out: The Hyper-learning Revolution Will Replace Public Education,” foretold of an inevitable hyper-learning revolution that would inevitably displace the thousand-year-old “technology” of the classroom, which, he argued, had “as much utility in today’s modern economy of advanced information technology as the Conestoga wagon or the blacksmith shop.”

The hyper-learning revolution Perelman prophesied last century has only just begun. New media convergence is drastically redefining the modes and conceptions of human communication at all spheres of humanity, but the revolution is nascent, particularly in the realm of formal schooling/education, which is increasingly privatized, leaving public school systems with ever-diminishing tax bases with which to overhaul an antiquated system.

The digital revolution in communication has completely altered old paradigms and disintegrated ancient and antiquated power structures and modes of conception. The communication revolution has the potential to revolutionize teducation.

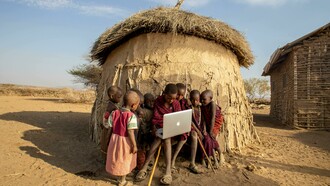

Convergence and new media based technological advancements have, however, already drastically changed the way humans communicate in less than a generation. Communication can be more streamlined, savvy, sensual, seductive, profound, misinformed, and faster than ever before. School systems, however, have not adapted at the same rapid pace as many students, especially digital natives – young people who grow up immersed in new media and digital technology.

One potential paradigm shift in the realm of education could be the traditional pupil/master relationship. Digital natives, most of whom were born after the year 2000, are so incredibly attuned to digital communication–particularly digital music and computer software–that the old conceptions of education are eroding rapidly.

One feasible way to close the technological chasm that exists between modes and methods of schooling as they presently exist with students raised in the Digital Age is by the implementation of more music into all areas of academic inquiry. A potential part of the solution to this widening communication chasm might be addressed in part by putting music technology such as computer software like GarageBand, hyper-instruments and MIDI in both students’ and teachers’ hands. Humans are naturally creative and naturally musical. It seems only natural that an actionable way to address the crisis in American education is to make the process entrenched in the process of making music, whether the class is STEM or the humanities, as much as possible.