The changes the world has experienced after WW II have probably been more intense than over the past centuries. However, which among those changes could be singled out as the most important? There is little doubt that this is the impact of knowledge and innovation.

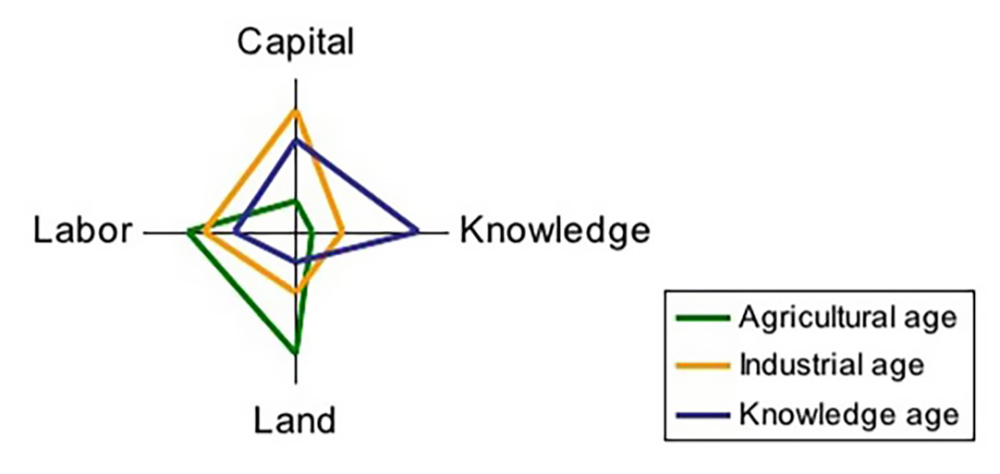

The graph below is showing very clearly to what extent knowledge (as one of the four economic factors) has become by far the strongest factor when comparing the pre-industrial and our post-industrial era.

The reason behind this fundamental change lies in the very nature of knowledge, the growth of which was undoubtedly exponential. Actually, each stage was enabling researchers and innovators to operate in a very different, productive environment: using totally new tools and reaching even unexpected results. Therefore it is fully justified to refer to the post-industrial economy as the knowledge economy.

Let us have a look at the top 10 criteria defining the knowledge economy:

Sophisticated, smoothly functioning market with an effective regulatory system—protecting public interest;

Well-functioning innovation ecosystem, including entrepreneurship support;

Focus on the production of high-value-added products and knowledge-intensive services.

Advanced science and R&D in corporate and public domains (GERD over 3% of GDP);

Well-educated population & highly skilled, creative, and motivated & innovative workforce (at least 40% of 29-35-year-olds with university degrees);

Good physical infrastructure, supporting the productivity of economic actors and providing high-quality living conditions;

Stable and democratic political system, based on the rule of law;

Sustainable social cohesion—no excessive socio-economic differentiation;

Knowledge, innovation, and entrepreneurship are culturally accepted as key pillars of progress.

Well-integrated into the world economy, fair partnership with foreign investors.

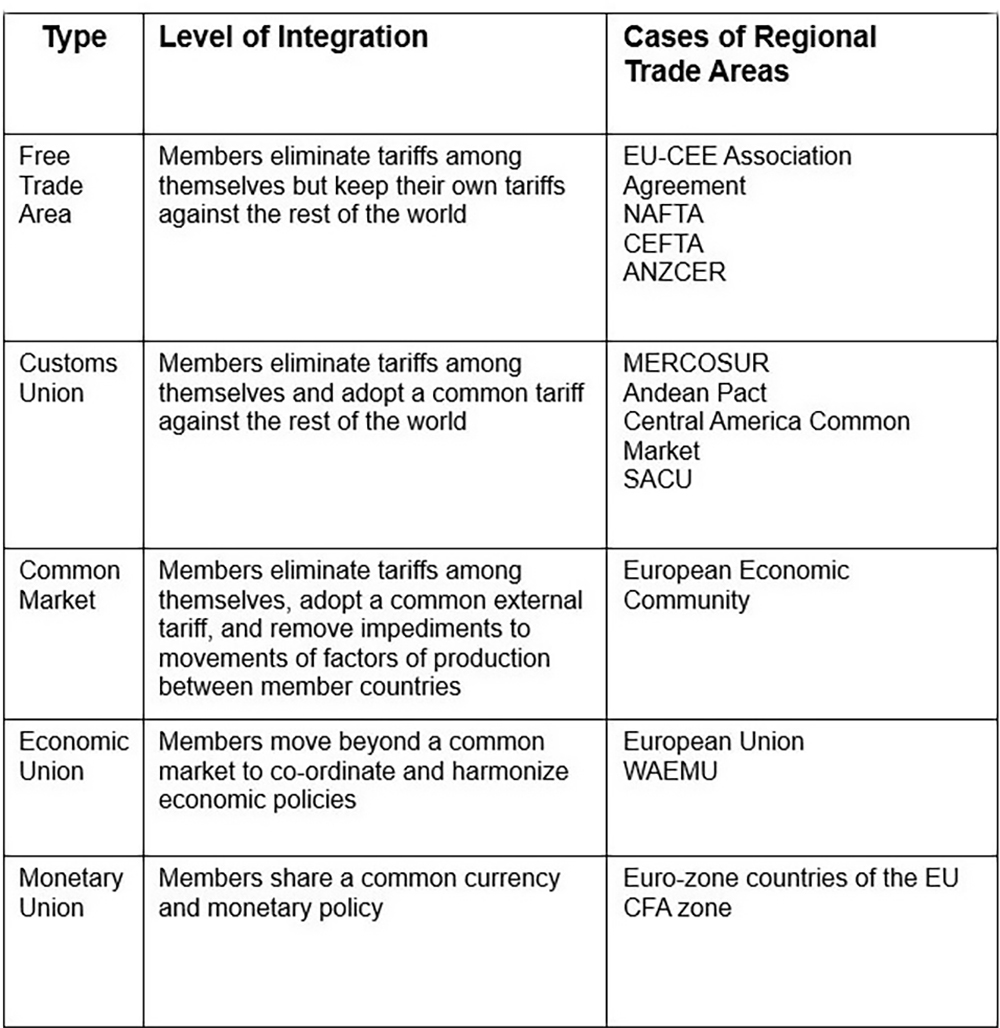

Based on literature, there is a commonly accepted classification of regional integration steps or types, expressing the stage of the integration process—starting from a free trade area and finishing with the monetary union.

Usually the process actually advances in these steps, but it is difficult to forecast whether a grouping will really follow all these steps or start more ambitiously and experience the progress accordingly. This depends on many internal, and even some external, factors.

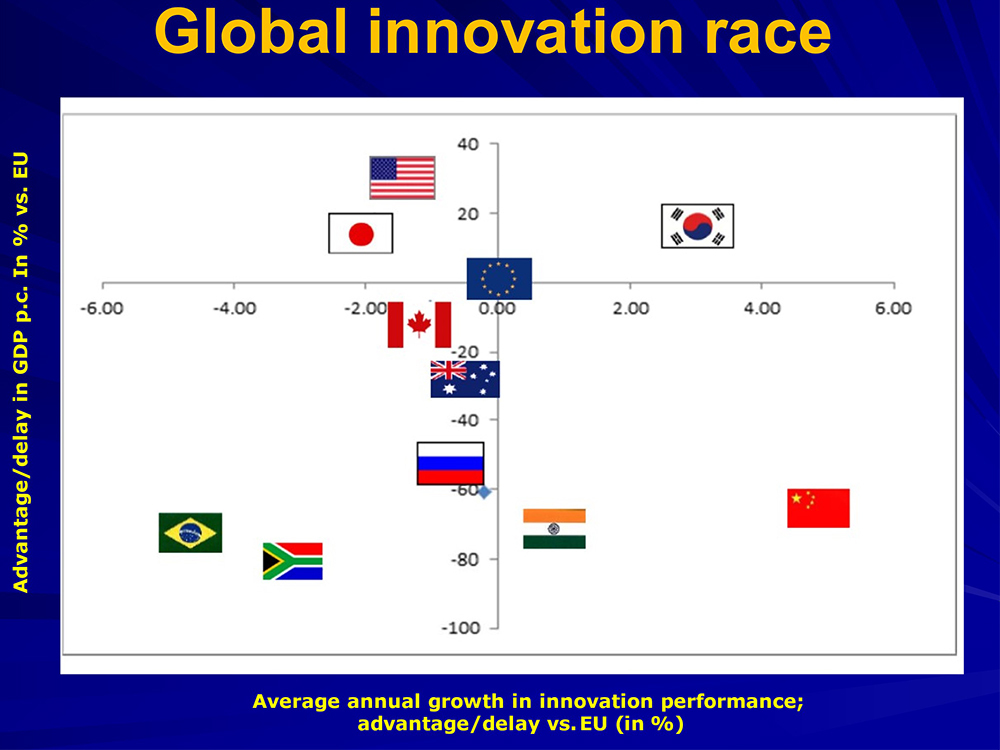

Taking this into account, one cannot be surprised by the two graphs below, showing the position of 11 major economies (in 2020) vis-à-vis the EU average in terms of innovation performance.

Korea is not only better placed than the EU but also advancing quicker. Though 70-75% behind the EU, India, and particularly China, are growing quicker. The US and Japan (as well as Canada, Australia, and Russia) are behind the EU but growing faster (which does not apply to Canada, Australia, and Russia).

An important factor in reaching innovative excellence for a country is the quality of its education system and the share of youngsters reaching university degrees.

In these conditions itis fully understandable that economic operators are strongly interested in as large markets for their products and services as possible—definitely beyond their national borders.

This is the background for the processes of regional integration, which normally starts as purely economic and—sooner or later—develops into certain political dimensions.

As we could identify from various sources, there are currently some 17 regional integration groupings, and they fall into the following categories listed above:

9– Free Trade Zones.

4– Customs unions.

2– Common Markets.

2– Economic & Monetary Unions.

Most of the regional integration groupings were created between 1951 and 1969 (6 of them), and the same number were created after 1990. Below we can see the timeline for all 17 groupings:

Looking at where around the globe integration processes have so far been most numerous, we can see that they were in Asia-Pacific regions—primarily due to geographic fragmentation—and most intensive in Western Europe, which has the longest tradition of nation-states, who have realized that further progress depends on enlarging markets. This was properly realized by the respective governments, starting back in the early 1950s.

It would be mistaken to disregard also another factor contributing to Western European integration—still in the period of the Cold War: namely, the pressure from Russia.

Starting with 6 Western European countries—led by France and Germany—Italy, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg, the process started in 1951 with the Coal and Steel Community. Only 6 years later these countries signed the Treaty of Rome—by which the European Economic Community was created. In 1972 nine new members joined, and in 1979 direct elections were held to represent citizens of 15 EU member states in the European Parliament. Expansion continued, and by 1992 the European Single Market became a reality, followed in 2002 with the introduction of the single currency, the Euro, and in 2007 the EU already had 27 member states.

Besides the unprecedented success of economic integration, an important political feature has to be emphasized: members and votes in the EU Council and European Parliament give preference to smaller members: for example, in the Council, Germany (with 90 million inhabitants) has 29 votes, and Slovenia (with 2 million) has 4 votes. This is a reassuring democratic feature of the EU decision-making system—highly appreciated by the smaller member states.

Although EU is active practically in all domains of public life in member states, its budget remains at 1% of their GDP, and about a quarter of it goes to support the less developed member states. Therefore, it is generally agreed that it is so far the most successful regional integration in the world.