Aristotle once stated that man is by nature a social animal, emphasizing the inherent need for social interaction. Over time, this need has transformed into the concept of the public sphere—a space where individuals come together to discuss and address societal issues and, through these discussions, influence political action. A Georgian tale comes to mind when thinking about the strength found in unity. A dying father calls his children to his side and gives them a single arrow to break. They do so easily. He then gives them a bundle of arrows and asks them to break it. They cannot. The father explains that while individual arrows can be easily broken, a united bundle is much stronger. This mirrors the nature of the public sphere: while individual ideas emerge from individuals, the collective strength and unity formed in such spaces create a force for change and improvement (in positive cases).

Jürgen Habermas, a key figure in the Frankfurt School of philosophy, significantly expanded on the concept of the public sphere in his groundbreaking work The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962). Habermas’s work traces the evolution of the public sphere, arguing that it took shape during the Enlightenment, where new public spaces like salons and coffee houses became central to free discussion and the exchange of ideas. These spaces marked a shift toward an open, communicative rationality that became the foundation of modern public life. According to Habermas, the Enlightenment played a crucial role in shaping modern society by creating a public culture grounded in reasoned dialogue and communication, where ideas could be freely exchanged and discussed among citizens.

At the core of Habermas's theory lies the distinction between the "public" and the "private." While the concept of "public" may seem familiar to us today, Habermas argues that the modern idea of the public sphere began to take shape only in the 18th century, although its foundations can be traced back to ancient Greece. In the Greek polis, free male landowners were the only ones permitted to participate in the political life of the city-state, while women and other groups were excluded. Over time, this space expanded to include a new class—the bourgeoisie—who opposed the authority of the royal court. Through their collective discussions, these bourgeois citizens began to demand recognition of their rights, and thus the public sphere gradually gained strength at the expense of the monarch's authority.

As culture and education began to spread, particularly through the written word, the public sphere became more active. The development of print culture and the gradual easing of censorship opened up a space for intellectual critique and debate. Cities became centers for the dissemination of ideas, challenging the once-dominant royal courts and creating a contrast between the cultural and intellectual life of the bourgeoisie and the older systems of aristocratic power. As Habermas observes, “an educated middle-class bourgeois avant-garde has learned the art of critical public debate through contact with the ‘elegant world.”

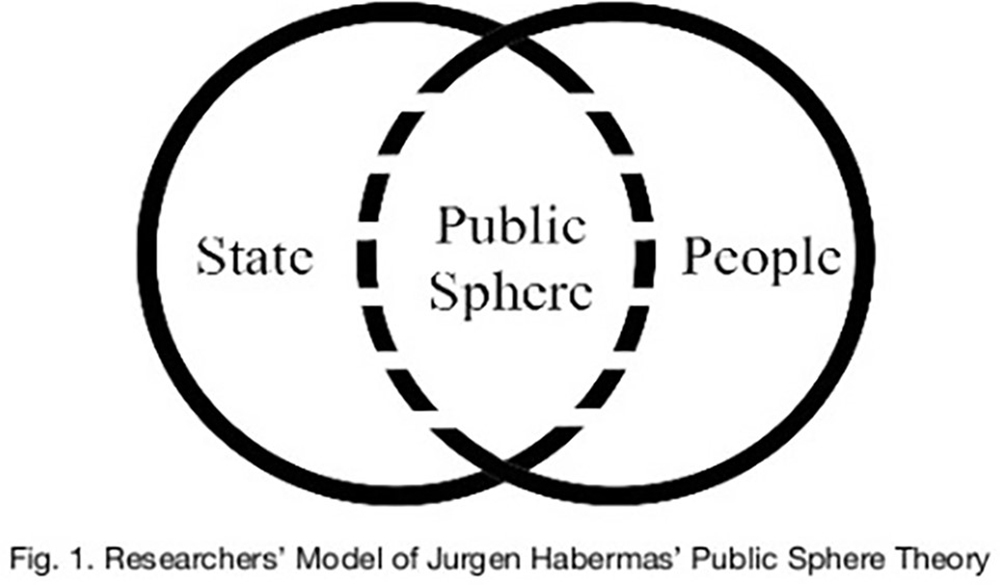

To further understand the nature of the public sphere, Habermas examines the concept of Öffentlichkeit, which refers to public visibility or publicity. The public sphere, according to Habermas, arose as a counterpoint to the royal court, with individuals forming assemblies to regulate and challenge the arbitrary power of monarchs. This shift laid the groundwork for the modern legal system and the notion of fair governance. It was in these public spaces that social issues were raised, discussed, and acted upon, leading to the development of new political and cultural norms.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, various spaces such as salons, cafes, and coffee houses became sites for important intellectual and cultural discussions. These spaces did not depend on social status or wealth; rather, the focus was on intellect and the ability to engage in thoughtful debate. Initially, the royal courts served as gathering places for intellectuals and artists, but over time, the function of these spaces shifted. In cities like London, Paris, and Berlin, coffee houses and salons became central to the intellectual and cultural life of the bourgeoisie, fostering an environment where ideas could be freely exchanged. These discussions were not limited to art and culture but extended to politics and social issues, with the goal of improving society through reasoned debate.

In England, for example, coffee houses were diverse, bringing together both the upper and lower classes for intellectual exchange. In contrast, the French salons were largely exclusive to the bourgeoisie and aristocracy, though they allowed women to participate in the discussions—an unusual feature compared to other European salons. German salons were less vibrant but still contributed to the development of the public sphere by providing spaces for intellectual discourse, even if they were more modest in nature.

In Georgia, a similar cultural development occurred toward the end of the 19th century, though Habermas did not specifically address this in his work. In Tbilisi, a number of artistic cafes, such as Kimerion, Blue Rider, and Sofia Melnikova's Fantastikuri Dukani, became centers for intellectual and political discussion. These cafes were not only places where artists and writers gathered but also where political ideas began to take shape. The discussions held in these spaces influenced the cultural and political identity of Georgia, contributing to its modernization and the formation of its national consciousness.

Habermas’s theory of the public sphere provides a framework for understanding how the public sphere, through intellectual and cultural debate, has shaped modern society. The bourgeois public sphere, emerging from the Enlightenment, laid the foundation for the democratic ideals we hold today. These spaces—whether coffee houses, salons, or cafes—became sites where critical thinking flourished, ideas were exchanged, and societal progress was achieved. Through open discussion, these spaces fostered the development of a better, more informed society, where the power of unity and reasoned debate could shape the future.