Amanita is pleased to present Vedrai, vedrai Francesco Cima’s first solo exhibition in New York and third with the gallery. Francesco Cima (b. 1990, Pietrasanta) graduated in visual arts at Academy of fine arts in Venice in 2019. He currently lives and works in Venice. Since 2015, he has participated in numerous group exhibitions in Italy and abroad. The attention to detail, as well as the instinctive ability to connect seemingly distant physical and temporal spaces are some of the peculiarities that characterize Francesco Cima’s paintings. Through thinly painted brushstrokes, Cima does not simply render views, but vast territories where infinitely many dimensions can find refuge, pushing the material confines of the oil painting beyond the imaginable. The main file rouge in his works is the presence of a crepuscular light that softly embraces the majority of his settings, echoing the emotional reverberations of Romanticism, to which Cima feels strongly indebted to.

Two thousand and twenty-four: Pluto sizzles captive in Aquarius. Experts advise against staying indoors; on the contrary, they invite to gather precisely during the hottest hours. Idealism, nonconformity, rupture - these are the watchwords that, according to star forecasters, will mark our steps until 2044.

We can already see it: anti-celebrity movements, anti-war unions, outrage, and numbers never before recorded. The old world trembles: fathers, mothers and grandfathers are being tried for responsibilities they were unaware they had, statues fall betrayed by the weight of their own legs.

And this is not the first time it has happened, assuming you are willing to believe it. Last time, under the same sky, both the American War of Independence and the French Revolution were fought and won; and before that, in 1543, Copernicus came forward to tell us that no, we are not the center of the universe. In this climate of fierce solidarity, whereby the unsuspecting are forced to take a stand or succumb, it is even more important to ponder the question that has never ceased to fascinate art critics and philosophers: what is the role of the artist? Well... none.

In fact, if we want to listen to thinkers such as Martin Heidegger, Ernst Bloch, Gilles Deleuze and many others, the artist naturally fulfills his own anticipatory impulse regardless of a desire to denounce. This means that the artist, visionary and nonconformist, contributes with each of his works (often unintentionally), to the creation of the world that will be, by virtue of his representational capacities and a hypersensitivity in which are mirrored, inevitably, the instances of the present of which he or she is a part. If, therefore, the artist is bound to the contemporaneity in which he operates, his work is not: excluded from a linear conception of time, the work of art no longer has anything to do with the moment in which it was generated.

From this reflection, it is legitimate to assume that the present in which we live has been shaped by the works of art of the past, while what we see here, today, already has to do with a future about which we know nothing yet.

Another question then arises: how long does it take for the represented future to manifest? Hard to tell, since the units of measurement of the artistic field are mostly currents and movements, constitutively unstable concepts.

While proceeding with nothing but a handful of clues and contemplating the certainty that this future will come true regardless of a when, an attempt at a general analysis of the contemporary art scene is no less urgent.

At first glance the latter shows itself as colorful, polymathic, iridescent, and autonomous as never before. Stigmas concerning degrees of nobility with respect to the representation of a given subject have not existed for centuries; most of the existing materials, minus the economic discriminator, are available; the color spectrum and our way of perceiving reality have almost no secrets left, and every shade of color has already been named.

Adding that the validity of a style is no longer a matter of debate (beyond personal aesthetic judgment), and the artist’s freedom regarding both formal and content choices regarding his works now constitutes a core value, one would say that art, contrary to the society in which we live, has long since negotiated its own peace.

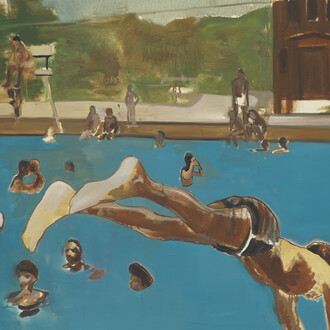

And what is the role of Francesco Cima’s paintings in all this? Each of them constitutes a promise, namely that in the garish and somewhat chaotic reality of the future, all will be well. There will be room for contemplation, for introspection, for minutes of silence and meditation stolen from the hours. We will be able to put down roots, experience the imperturbability of the mountains, enjoy sunrises and sunsets that are very rapid compared to the lives of trees, and have time to explore and accept our dark side.

This dilation is made possible by the depiction of pictorial subjects that are in themselves very close to the idea of the sublime, amalgamated with an almost nonexistent temporality. The when, in Cima’s paintings, exists; yet the scene might represent one among many moments in between the birth of grass and the forever, until a moment before the sun explodes.

In these woods that simultaneously are, were, and will be, one can find a refuge from modernity and frenzy. The same drippings of color, which constitute an initial geographic trace on which the brush will later go to work, take time to make themselves. And the way the artist handles inspiration is the same as fishing: in the calm he remains focused, his senses protracted toward the water waiting for a scenery to bite.

This is how Lamina Rossa and Tourandot were born, one formed from an unexpected look at the bricks of the Venice cemetery and the other as a rework of the Massaciuccoli marsh.

Cima’s intention is to give form to the nostalgia of invisible things, an ode to the possibilities enclosed by the light of a distant window. And he proceeds by following a motto: to those who say, “write like nobody’s reading”, he replies “paint like everybody is watching”.

(Text by Beatrice Timillero)