As a young person growing up in India in the 1970s and 80s, the struggle of southern Africans against apartheid—an institutional form of race-based segregation and discrimination that its colonial government imposed—was one that we frequently encountered. Tales of brutality that we heard were horrifying, but stories of the movements for freedom led by some of recent history’s most iconic figures inspired us. India as a people, including its government, was strongly and vocally supportive of the movement, having ourselves felt the pains of colonialism till not so long ago. And so, when South Africa finally threw off the shackles of apartheid colonialism in the early 1990s, it was a powerful global symbol of hope. And when Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, and others set the country on a path of ‘truth and reconciliation’ rather than vengeful bloodshed against white people who remained, we looked at South Africa with eager anticipation. The foundations for peaceful transition towards a future determined by some of the world’s most ancient peoples and their brave new catalysts appeared to have been laid.

Today, that dream appears to be rapidly receding—at least at one level. On two recent trips to the country—admittedly only a surface glimpse—I found and heard stories of betrayal by the country’s leadership that were depressing. The African National Congress (ANC) was the face of the freedom movement, building on mobilization by communities, women’s organizations, trade unions, religious groups, and others. The ANC in government initially did well in laying the material foundations of democracy, including a progressive Constitution and relatively free institutions such as the judiciary, a human rights council, and the media. High priority was given to basic needs like water, health and education and some serious land reform attempts, including the restitution of community territories grabbed by the colonial regime.

But it then struggled to sustain the momentum. According to Roland Ngam of the Rosa Luxembourg Stiftung Southern Africa, two challenges derailed the process: “the 1990s intellectual generation chose to implement World-Bank-inspired trickle-down politics; and after brutal intra-party squabbles, the 2010s generation launched an ‘it’s our time to eat’ style of politics that caused rampant corruption and poor service delivery to collapse most of the state’s capacity.” The ANC, with no serious challenge by any other party until recently (it now forms the government in coalition with nine smaller parties), has increasingly enabled powerful private corporate interests to grab lands and resources and dictate development policy (a move that, according to long-standing South African analyst and activist Patrick Bond, began even under Mandela’s leadership). On my recent trip, I was fortunate to be at a preview screening of ‘Blue Burning’, a brilliant expose by filmmaker and 'Oceans, not Oil’ activist Janet Solomon of how almost all of South Africa’s coastal waters are being sold to companies like Shell for oil and gas exploration. Inland, mining interests are already ravaging natural ecosystems, farmlands, and pastures.

Reversing the slide: resistance and reconstruction

At another level, though, the early dreams of forging a path of peaceful justice are re-appearing in several people’s movements and initiatives. It seems that most recent transformations towards greater justice, ecological regeneration, and other progressive directions have been led by such movements. These build on the brave work of grassroots movements against colonialism and apartheid. One powerful output of these was the Freedom Charter in 1955, a people’s manifesto that became a basis for the freedom movement and the 1996 Constitution.

Perhaps most inspiring are those on the ground, from communities and collectives rooted in their places and spaces. In September this year I visited the region of Xolobeni in the Eastern Cape, where the Amadiba people have been resisting several kinds of destructive ‘development’ projects for over two decades: titanium mining, oil and gas exploration, a'smart’ city, a highway through fertile agricultural lands and one of the country’s biodiversity hotspots. They are also forging their own alternatives, sustaining their commons-based agroecological livelihoods and innovating on some new ones like community-led ecotourism. In Sigidi village, I met up with Nonhle Mbuthuma, one of the founders of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, set up to organize the community. She stressed that when government officials and others from outside call them ‘poor’, they are very wrong: “We have land, we have nature; how can we be poor?”

Across the country in the western Cape, women have taken a lead in resisting inappropriate impositions from outside. Davine Witbooi, overcoming domestic violence and threats to her life because of the causes she has taken up, spoke to me about the natural beauty of their region, the sustainable land or marine-based livelihoods its people have, and how their movement is trying to protect these against destructive mining.

In Durban and other cities, over 150,000 shack-dwellers, tired of neglect and worse by an uncaring government, have mobilised as Abahlali baseMjondolo (Residents of the Shacks). Their struggle is for rights to land, water, housing, food sovereignty, gender justice, and dignity in all aspects of life, as well as for deep democracy in society as well as within themselves. As they say, “We assert that everyone has the right to participate in all discussions and decision-making relevant to them and that no one should think or decide for us. We are clear that our movement belongs to our members and not to any NGO, donor, political party, organisation, or network that thinks that it has a right to rule the organised poor.”

Alliances and networks: towards collective strength and visioning

South Africa has a long tradition of resistance and protests, in what Patrick Bond calls the “highest rates per person in the world." It is this heritage that saw massive mobilisation for universal free access to antiretroviral medicines for combating HIV-AIDS, in what Bond calls “one of the world’s great victories against corporate capitalism and state neglect.” This is also an example of how larger networks and platforms provide a connecting, unifying force that can greatly expand the power of individual localised movements like the ones mentioned above. Some have been initiated by the grassroot catalysts themselves. For instance, Davine Witbooi told me that she and other women started the West Coast Food Sovereignty and Solidarity Forum, realising that across the country’s coasts, communities were facing similar challenges.

The Rural Women's Assembly brings together women across South Africa (and other African nations) for “securing food sovereignty, safeguarding biodiversity and ecological heritage, and striving for a world free from violence against women." The WoMin African Alliance, which began in South Africa and is now pan-African, brings together movements against extractivism (mining, etc.) and for ecofeminist development alternatives.

Small traders, severely marginalised by big business and by discriminatory prohibitions during the COVID period, have united under banners like the National Informal Traders Alliance South Africa (NITASHA) and the South Africa Informal Traders Alliance (SAITA). Strong mobilisation amongst unemployed people has spawned a number of networks, such as the South Africa Unemployed Peoples Movement.

Two national-level platforms that are bringing together many grounded movements across different sectors are worth highlighting. One, celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, is the South Africa Food Sovereignty Campaign (SAFSC). Arising from the trauma of continuing hunger and malnourishment in a huge part of the population (according to many estimates, over 20%), the SAFSC brings grassroots initiatives of food security and sovereignty by farmers, fishers, and other collectives into a series of dialogues and visioning exercises with academics, activists, and small traders/businesses. It has framed draft policy and legislation and pushed for their consideration by the South African Parliament, as well as brought out several practical toolkits for ground-level transformations. Advocacy for the policy and law dimmed during the COVID period but has been recently renewed; on October 16th, I was fortunate to be part of a demonstration outside the Parliament, demanding consideration of a draft People’s Food Sovereignty Act of 2024 that the campaign has put together after extensive consultations.

From within the folds of the SAFSC grew a second platform, dealing with the climate crisis. This was a natural progression, given the increasing evidence of climate-induced food and water stress across the southern African region, especially in the years following El Nino in 2014. While such stress is of course taking place in many other parts of the world, this region is especially badly hit—it is likely to see twice the global average temperature rise, and most of its territory being arid or semi-arid is already prone to water stress. Regular and irregular occurrences of drought and floods, cloudbursts, temperature spikes, and so on, are affecting millions of people.

The Climate Justice Charter Movement (CJCM), catalysed by the Cooperative and Policy Alternatives Centre (COPAC), emerged in 2018-19 in response to the utter failure of the South African government to grasp the severity of the crisis and take appropriate steps. One of its most innovative and promising steps was to bring into the dialogue and encourage the catalysts from within, worker groups and unions. As senior trade unionist Dinga Sikwebu told me on a visit in 2023, worker participation is based on the recognition that a transition out of the climate crisis has to do justice to millions of workers in the fossil fuel and related industries, ensuring their re-occupation in dignified livelihoods. So, the CJCM included many of the country’s biggest unions (metal workers, mine workers, teachers, etc.) and their national alliance, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), in dialogues and visioning exercises with feminists, ecologists, youth, and others.

The resulting Charter and associated policy documents on several subjects (e.g., mobility, food, macro-economy, rights of nature) are powerful visions and pathways out of the climate crisis. Unfortunately, divisive party politics and other factors have led to COSATU and many of the individual unions dropping out of or reducing their involvement in the process. In any case, there was always the question of how deep the consciousness about such transformations was amongst the rank and file of the unions. Even civil society itself is not united (there are a few other climate-related platforms, such as the Climate Action Network), an issue which I could not go deeper into. But the CJCM continues to mobilise in various ways, in particular bringing in grassroots movements and informal worker unions as the building blocks for any kind of just transformation. One of its strategies for such collective mobilisation, according to CJCM National Convening Committee member Charles Simane, is a climate emergency policy platform at the national level, as well as local forums in several parts of the country.

Most of these regional or national networks also link to global ones, such as La Via Campesina in the case of farmers or Streetnet Alliance in the case of informal traders and vendors.

Flower of Transformation: Toward holistic transformation

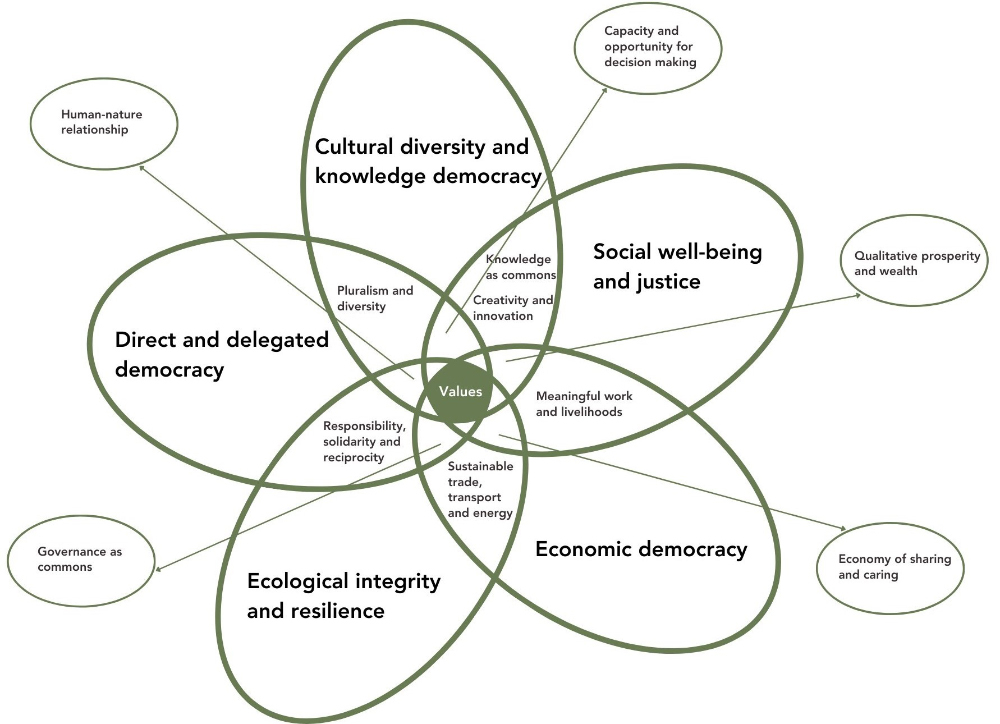

A powerful and actively promoted aspect of these movements is their intersectionality, or attempt to cut across various sectoral, class, and ethnic divides. One way to understand this is as a Flower of Transformation (see figure below), a tool emerging from experiences of alternatives in India. In this, initiatives for positive change are seen as being within political, economic, social, cultural, and ecological spheres of life, but enmeshed and intersecting with each other. Changes taking place in any one sphere have impacts on the others. For instance, economic inequality and poverty in South Africa are profoundly linked to greater vulnerability to climate impacts and to food insecurity, and gender discrimination and inequities mean that these impacts are felt even more acutely by women. In attempting transitions out of these multiple crises, an understanding of their intersecting nature makes holistic transformation more possible.

As Rosheda Muller of NITASHA told me, small traders realise the need to ally with feminist, climate, environmental, and other movements to push for policy and on-ground changes that benefit all of them. Vishwas Satgar of COPAC, one of the anchors of both SAFSC and CJCM, says that a narrative that brings together Marxists, feminists, and ecologists into a ‘democratic ecosocialism’ is urgently needed. Awande Buthulezi, a member of the CJCM National Convening Committee, mentioned that the process deliberately involved a wide range of interests: small farmers and other water-stressed communities, faith-based groups, media, social justice and human rights advocates, academics and climate scientists, youth, legal experts, feminists, conservationists, and others.

Also evident, implicitly embedded or explicitly articulated, are a set of ethical values or principles in the work of these movements, as seen at the core of the Flower. A commitment to the commons and collective interests as opposed to hostile individualism and privatisation, relations of solidarity and care, the rights of both humans and the rest of nature, diversity and pluralism, autonomy and democracy, equality and equity, and others are the foundation of both the local and the national level platforms mentioned above.

There are also the beginnings of bioregional or biocultural regional approaches, recognising that pathways out of the climate crisis have to be across the southern African region (including Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique), and some initial steps towards incorporating the ‘rights of nature’ so as to go beyond a human-centred approach. Beginning to be embedded in CJCM and other movements, these are promising narratives and actions towards more holistic transformation.

But what is the future of these transformations in South Africa?

I asked several civil society and academic actors whether there was any political party consistently backing demands for justice, and the overwhelming answer I got was an unhesitating ‘no’. On being further pressed about the politics of SAFSC, CJCM, and other such processes, some of their key participants and activists, like Samantha Hargreaves (one of the founders of the WoMin African Alliance), admitted that for too long, movements have been focused on getting the state to act. While it remains important to make the state accountable and responsible, for after all parties are elected with a mandate to serve the people, there needs to be a much greater attempt to radicalise democracy by enabling communities and collectives on the ground to reclaim power.

This is also because, as Roland Ngam told me, the country’s middle class has betrayed the ideals of the struggle for freedom, distancing themselves from the poor, keener to “fight fiercely to maintain its gains rather than spread the benefits of democracy to more previously disadvantaged people. In this scenario, a mansion in the village and Mercedes and Louis Vuitton bags are absolute must-haves, even if it means diverting money meant for a water project in order to get what one wants.”

And yet, some of the democratic institutions and principles installed soon after throwing off colonial shackles are proving useful. South Africa’s Constitutional Court has been one of the last bastions of fundamental rights and ecological sanity in the face of the ruthless assault by state-sponsored corporate interests. In a number of cases, such as the ones filed on behalf of the Amadiba people against mining and seismic exploration for oil/gas, it has interpreted the Constitution and relevant laws to validate the demand that consent should be sought from communities for infrastructure or other developments in their territories, or that due processes of impact assessment and clearance need to be followed where they have been sidestepped.

However, as told to me by Vinodh Jaichand, a Professor of Law and a former member of the South African Law Reform Commission, this is a fragile bulwark, for it depends heavily on the mindset of a handful of judges. Many of those currently presiding in this Court are from the generation that fought for freedom, and there is no saying how a newer generation will view issues of human and environmental rights. Besides, it has not been consistent in defending constitutional rights, as for instance when it did not back a movement for the commoning of water run by economically marginalised communities in Johannesburg and elsewhere.

For activists of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, the autonomy to take collective decisions in all matters affecting their lives is a crucial fulcrum of democracy, especially given the flip-flop record of all formal institutions of the state. Arguments for food and energy sovereignty also point to a politics that is much more radical than ‘capturing the state’, which has unfortunately been a focus of conventional Leftists across the world. South Africa’s movements for justice are perhaps not yet in a phase of questioning the nation-state itself (as do the Zapatista autonomy and Kurdistan freedom movements), but there are, as Ngam stressed, many elements of radical democracy in their articulations and visions.

There is a long way to go, as everywhere else in the world. South Africa needs many more popular movements of the kind mentioned above, many more emancipatory education initiatives, and the coalescing of such movements into holistic, sustained platforms. These initiatives have to build greater critical mass amongst the country’s diverse peoples to affect macro-transformations. But at least on some counts they are already leading the way, showing the world what is possible, much as they did in the struggle against apartheid.