As I emerged from the subway station at Shin-Imamiya, staring at my phone and Google maps app, trying to orient myself, a distinguished looking elderly gentleman walked up to me and motioned for me to show him my phone. He could tell I was new in town and he intended to help me. He took a look at my phone, handed it back to me, and walked with me to my hotel. He could not speak English and I could speak zero Japanese – no matter. Smiling cheerfully, he walked with me in silence until we arrived at my hotel, bowed to me and went walking in the opposite direction – he had gone out of his way to help me.

A few days later at a subway station, a male high school student walked up to me and said, in perfect English, "Sir, you look lost. Can I help you?" After I told him the train line I needed, he walked with me to make sure that I got to the right platform. He did not just point and leave, he, like the elderly gentleman, walked every step with me.

I found this type of kindness and friendliness throughout the city. Osaka is the kind of city where people notice when you are a bit lost or confused or in need and they come over to help. There is a Japanese term for the people of Osaka - なれなれしい —narenare-shii, which means “overly familiar”. I suspect it is a derisive term the people of Tokyo gave to the Osakans as the folks in Tokyo seem to embrace a different, let’s say more introverted (to be kind), lifestyle. I fell in love with the people of Osaka and their narenare-shii. They are not self-absorbed—they are very much aware of others and willing to lend a helping hand.

Just before World War II, Osaka was the largest city in Japan and the 6th largest city in the world as well as the largest manufacturing city in Asia. Osaka has a wonderful history and peace museum, and if you go through both of them you begin to realize that the hard-working, generous, humorous and entrepreneurial citizens of this city were victims of the militarism which was developed by the Tokyo elite in the 1930s.

The people of Osaka were and are entrepreneurial in spirit and not at all bellicose. They remind me very much of the hard-working and kind working-class people I grew up with in Chicago. Like Chicago, Osaka has a tradition of producing some of its country’s best comedians. I somewhat felt a sense of outrage and resentment that this amazing city could have been pulled into World War II.

It was the military leaders in Tokyo who hijacked the democratic government and turned Japan into a brutal and cruel war machine. It was the military which took the number one production center in Asia and forced it to convert to war production. At the amazing Osaka Peace Museum, a vintage classroom is presented showing how militarization even took over the Japanese school child's experience shortly before and during WWII.

Osaka is not as hugely significant as it used to be, as many Asian cities have developed since World War II, but it is still vital to Japan’s current economy due to its significant GDP contribution, large population providing a skilled workforce, still strong manufacturing capabilities, robust export activities, effective infrastructure connectivity, innovative tech environment, and its historical and cultural significance which produces tourism revenue. But I want to talk about Billiken now.

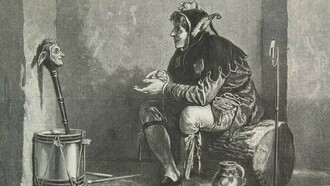

I cannot think of another city which has established its own (kind of goofy) god. Indeed, I had not even seen Billiken until I arrived in Osaka and began wandering around the neighborhoods near Nishinari. The Billiken concept was: The God of Things as They Ought to Be. It was clearly meant to be humorous and carried a deeply serious human desire in a very silly manner, like somebody joking about something to conceal his belief in it that others might scoff at. Billiken looked to be something to laugh at but to invest hope in anyway.

Like all really good gods, Billiken comes from a far away place. Mithras, Isis and even Jesus were worshiped in ancient Rome in part because a foreign origin gave some sense of authenticity and exoticism to these deities. Billiken also has this foreign sense of authenticity and exoticism as he was conceived by an art teacher named Florence Pretz in Kansas City, Missouri, USA. He came to her in a dream. She named him Billiken after the name of a little person waiting for the moon to visit earth in a poem by Bliss Carman. Florence liked drawing chubby little impish or elfin figures, which her dream figure resembled, and soon she designed and patented an image of the god.

A company in Chicago began to make little Billiken figurines as good luck charms, but kept their tongue in cheek by claiming in ads that the Billiken was more lucky than a rabbit’s foot in the hind pocket of the seventh son of a seventh son. They also started the trend of calling him “The God of Things as They Ought to Be”.

So Billiken was to be a lucky charm that mocked the concept of a lucky charm but still hopefully functioned as a lucky charm because it was wary of being one. This was the type of humor Osakans could appreciate and in 1912 a statue of Billiken was installed in Luna Park, near the still famous Tsutenkaku Tower. These days you see Billiken all over the Shinsekai district.

Thinking of Billiken as a token of good fortune or as a god is like joking about something that most likely doesn’t exist but you dearly wish it did. We know that our actions are often not what they ought to be – we should be able to control our temper, our aggression, our egocentricity and be kind and patient, show forgiveness, show mercy, engage others with love and respect and engage the world on a meaningful level, but it is so hard to do some of this sometimes.

With Billiken, we have something not especially serious to look to that might help us. We do and don’t expect its help at the same time. Billiken is the friendly, non-threatening, joyous and goofy savior we can turn to while pretending we are turning to him as an ironic joke.

Let’s look at his iconography. He has a pointed head. This indicates intelligence and wisdom. Wizards and scholars wear pointed hats. Buddhist stupas are pointed. He has a unique smile. In Asian art a smile on a god or bodhisattva’s face usually means compassion, peace, or enlightenment. Billiken has a mischievous, almost flirtatious smile. He looks a bit like a satyr. There is an element of the weirdly erotic in the little guy. He is of the earth, a god from the earth who understands our desires. He has a pot belly. Like the gods of prehistoric times, his belly represents abundance.

His oversized ears are like those of Ganesh. They allow him to hear needs and requests. Finally, he is sitting and showing the soles of his feet to you. Billiken knows that you know that he is showing his soles to you to show how comfortable he is with us. In some religions the head is the apex and the feet represent “the lowest”. That part of him which touches the ground is the part we rub on Billiken for our good luck.

Billiken is the god who looks and pretends to be too goofy and frivolous to be useful, purely in order to serve us better as a god who can get us to where we ought to be socially and personally, even if we do not want to seriously seem as if we wish for this, while seriously wishing for this.