China clearly constitutes the most impressive experience of economic and social development in the world. More important than judging it, is understanding how it works. And there is much to learn.

In short, ‘common prosperity’ is essentially aimed at balancing efficiency and fairness, growth and sharing, so that the benefits of economic development can be more evenly distributed in the whole society.

(China's new road to prosperity)1

We all have opinions on China, but very few have any understanding of how things work in this country. In part this is due to extremely poor journalism and overall information. An important factor is the fact that the so-called West, and in particular the U.S., are so interested in disinformation. Most commentaries are highly ideological. But understanding China is crucial, and no simplification can work for such a giant and complex country. I am not a specialist on China, but I have been there several times, and I follow the main publications on China Daily, CGTN, and other Chinese sources. We have lots to learn on how China organises its decision process. People love stickers, it allows them to classify China without studying it, so it becomes “state capitalism”, “market socialism”, and the like.

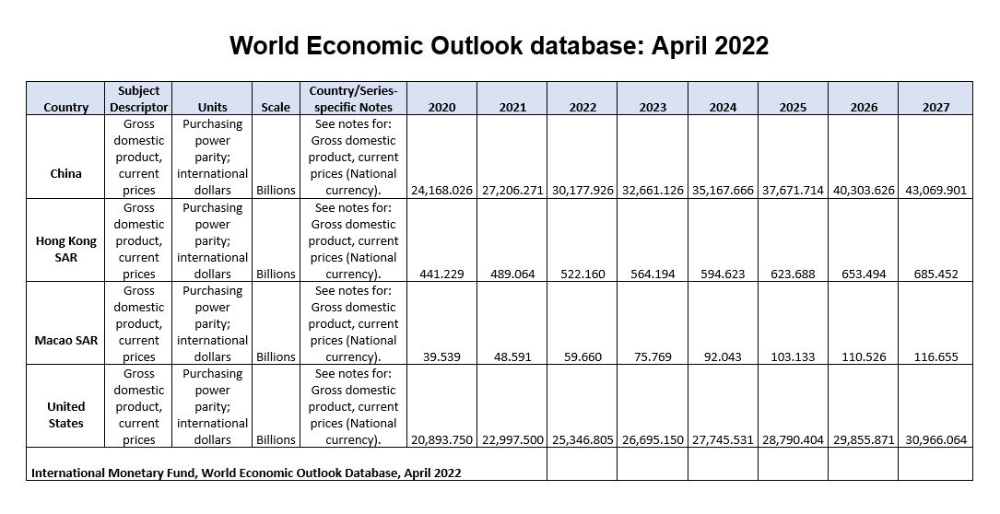

An obvious and important fact is that things work. In Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), meaning in real volume of production, Chinese GDP in 2022 reached 30tn dollars, against 25tn for the U.S., as shown in the IMF figures below.2 In real value of production, China moved ahead of the U.S. in 2017, and keeps moving.3 This fact has enormous importance, since it has been guiding the U.S. international policy, as we have seen with Trump and Biden reactions. A new world balance is emerging, a realignment seeking to isolate China and its products on the part of the U.S., while China is opening up through its economic and technological clout and bringing new opportunities to emerging countries.

But what interests us more here is how this country, emerging from feudalism and other dramas in 1949, has managed such impressive transformation in such a short period. An essential point is that the overall orientation of economic development in China followed, and is following, is practically the opposite trend the West adopted: instead of making the rich richer, stating that this will allow progress to “trickle down” to the poor, the whole Chinese effort, from the start, was oriented to solve the basic problems of the poorer part of the population, the huge majority. Efforts were directed to the most needed.

“During the last phase in this process, from 2013 to 2020, China embarked on a program of targeted poverty alleviation initiated by President Xi Jinping, to lift the final 100 million Chinese people from extreme poverty. This adds to the over 700 million people who exited poverty in the country since the reform and opening up period began. Since 1978, China has accounted for over 70 percent of the global reduction in poverty."4 These numbers have been amply confirmed, and they bring us a key transformation on how we think about economics.

In Brazil, during the 1964-1985 dictatorship supported by the U.S., the motto was, “Let the cake grow first, then we will distribute it.” In clear, it justified policies based on deepening inequality. Presently, Brazil continues as one of the 10 most unequal countries in the world. What the Chinese numbers show is that instead of the narratives that building fortunes for the rich will ultimately be good for the poor as well, there is no contradiction between economic inclusion and economic growth. It actually amounts to inclusive development. This is not a Chinese originality—it is what works, and we need it for the world. The figures on the economic stagnation of the bottom-half of the American population are explicit. The world figures on inequality are still more dramatic. It is not a question of ideology here, but of common sense, investing in what works, prioritising the basic needs of the populations.

A key instrument for China to promote simultaneously a generous people-oriented economic policy and investing in infrastructure and basic industry is its control of finance. In the recent decades, the West has promoted financial fortunes at the expense of productive growth. “Rising rates generally have positive impacts for financial firms as they lead to wider interest-rate spreads for banks and better investment returns on the portfolios of insurance companies and fund managers. However, they also slow the overall economy and reduce the cash available to households and firms while trimming demand for now-more-expensive credit.” The same report stresses that, “China is likely to expand its pilot use of its central bank digital currency (CBDC), dubbed the e-yuan, and may implement it countrywide.”5

The key issue is that China has the capacity to orient the financial resources towards productive investment and mass consumption with low interest rates—once again the reverse of what the financialisation in the West is accomplishing. Channeling money to productive investment raises the level of production, and low interest rates allow the corresponding demand expansion without inflationary pressure. According to The Economist, “China already manages both the money supply and interest rates with different sectors in mind. Since 2015, for instance, it has created hundreds of billions of yuan for the construction of affordable housing. More recently, it has instructed banks to lower interest rates for small firms.”6 Typically, a Chinese will pay 4.6% for a loan, which discounting 2% of inflation means a real interest rate of 2.6%. In Brazil, we face 51% for families, 21% for businesses, for an inflation of 4%—a scandalous financial unproductive drain, straight-face usury with phantasy narratives.

As part of China’s common-sense finance, external trade is tending to avoid the costs of the dollar intermediation. As China’s media network CGTN reports, they will “conduct their massive trade and financial transactions directly, exchanging yuan for reais and vice versa instead of going through the dollar.” It noted that China is Brazil’s biggest trading partner, and in 2022 the two countries did more than $150.5 billion worth of trade.7 This trend presently involves numerous countries. The dollar still is dominant, but as it is used to generate debt dependency rather than productive investment, more countries are resorting to bilateral exchange in their own currencies. In China, money is linked to the real economy, as banking used to be in the West.

Another key characteristic of China’s decision process is the way it avoided both market fundamentalism and State-centred simplifications. Deng gave a simple explanation of the Chinese pragmatism: when you cross a river, you must feel the stones with your feet. It is important to stress that China does not face a “situation” but a rapidly changing landscape—technological, political, economic, cultural. To give an example, China must reduce its dependency on coal and is doing its homework. It is moving to solar, but instead of building a big state company to produce photovoltaic panels, it built a big state company to produce basic machinery and equipment to produce the panels.

Thus, any private company in any part of the country can get a cheap loan at the bank, purchase the equipment, and produce panels according to local demand. In a way, the State provides a starter for the private sector to engage in environmentally important trends. It is a private-State mix, intelligent and pragmatic, with the State making the heavier strategic investments.

This also implies a different atitude concerning the relations with transnational corporations. China did open its economy, but not in a subservient attitude. Interested corporations have to negotiate how many Chinese will participate in the management boards and how much technological transfer will be ensured, defining balanced interests within the overall orientations of the Chinese economy. The dominant policy, in different countries, of “attracting” investment by lowering or eliminating taxes and environmental restrictions is avoided. And it works.

Another essential characteristic of the New China Playbook8, as Keyu Jin calls it, is decentralisation. China very soon abandoned the Soviet Union management model based on centralisation and gigantic ministries and chose a radically decentralised model. This means that central government in Beijing is politically strong and draws the structural lines such as environment policy, the option for the high-speed train system, the poverty eradication prioritisation, the huge rural exodus management guide-lines, and presently the science and technology options. But it is a small central government in that the implementation of the defined guide lines are rigorously decentralised.

Keyu Jin calls it a “mayor economy” while Arthur Kroeber, author of China’s Economy9, considers that China is even more decentralised than Sweden, where 70% of public money is directly transferred to local authorities. In Brazil, it is around 15%, and mayors have to travel to Brasilia to beg for the necessary funds. Neither the municipalities’ management works, by lack of resources, nor central government, mired in micro-negotiations preparing the next election. It is systemically inefficient. The U.S. did once benefit from agile local decision capacity, including local banks, before the giant corporations and platforms took over. China is essentially managed at the local level, where people, businesses, and the administration are familiar with the diverse challenges and potentials and ensure the necessary micro-negotiations and adjustments.

Family economic wellbeing depends not only on access to money—to pay the rent and daily purchases—but also on access to public consumption goods and services. We need security but do not buy police, as we do not buy hospitals, schools, parks in our neighbourhood, clean rivers, and so many services that represent roughly one-third of our income, through this indirect salary, with free public services universal access. Education, health, leisure spaces and the like are provided by the public administration, which makes them much cheaper and efficient than privatised social policies centred on maximisation of financial returns. This radically increases the overall efficiency of the Chinese administration.10

Again, it is not a question of ideology but of basic management common sense. Some things—like producing cars, bread, or tomatoes—can perfectly work as private enterprises, but education, health, security, or big infrastructures are more efficient in public hands. We are too complex economies to rely on ideological simplifications. The environmental issues are particularly dependent on public control. Chinese pragmatic approach based on what works better in what form of organisation not only made China much more efficient but brings us many lessons on how to organise ourselves.

Science and technology have become central in the context of the digital revolution in the world, and China not only defined progress in this area a national priority, but also generated a collaborative environment based on heavy public funding as well as partnerships with the private sector. Initiatives like the ORE (Open Resources for Education) ensure that innovations in any university or research centre are circulated among the whole network, so that no one is reinventing the wheel, and all institutions work at the top of the innovation wave in a synergic environment of collaboration and free access. China did copy—like everyone else—but presently it is being copied. The collaborative open access approach in science and technology is certainly much more effective than our patent and copyright jungle.

Let me add that these efficient guide lines are based on a political decision-making process based on training and accumulation of experience at all levels. Chinese comment with amusement on how in the U.S. Trump was elected without any idea of how public administration works and essentially reduced the tax payment levels of the corporate world that supported his campaign and resorted to aggressive external policy declarations. Xi Jin Ping had ample experience at the municipal level, getting familiar with the daily challenges of simple families, and gradually rose to his present position as he got deeper understanding of the overall workings of public administration.

Just as important, or even more, the Chinese administrators clearly understand that they are not responding to a situation but to an accelerated movement of change. It is a pragmatic approach, but not simplified. When Keyu Jin refers to “beyond socialism and capitalism”, she refers less to a new system than to the flexibility of adaptation to evolving challenges.

Notes

1 Jiannan Guo, Lei Zhang, Jincai He, China’s new road to prosperity, 13 January 2022.

2 IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, 2022.

3 Dean Baker, Real-World Economics Review Blog, China is bigger, get over it, 2023.

4 Wenhua Zongheng, Socialism is a Historical Process Vol.1 N.2, 2023.

5 Economic Intelligence Unit, EIU, Finance Outlook, 2023.

6 The Economist, 6 May 2021.

7 Ben Norton, Countries world-wide are dropping the U.S. dollar, 6 April 2023.

8 Keyu Jin, The New China Playbook: beyond socialism and capitalism, Viking, 2023.

9 Arthur Kroeber, China’s Economy, Oxford University Press, 2016.

10 Truman Du, Charted: Healthcare Spending and Life Expectancy, by Country, Visual Capitalist, 13 November 2023.