In the middle of a forest, trees stand as ancient witnesses, their branches offering sanctuary to myriad creatures. These silent observers weave themselves into the intricate tapestry of life, forging symbiotic bonds that transform them into living resonators. As one steps into this realm, the initial hush gives way to the vivid presence of birdsong—a testament to the deep bond between trees and their companions. This symbiosis is not merely functional but protective; it creates a community where safety, refuge, and nurture coexist. In Time as a shield, Sandra Mujinga’s first solo exhibition in Switzerland, this natural liaison finds a powerful echo in a forest of human creation. Here, time, like an invisible thread, weaves past, present, and future into a tapestry of resilience. In an enigmatic landscape of monumental, tree-like sculptures draped in textiles, time becomes both a protector and a witness. These towering figures, with heavy branches encircling their trunks and multiple roots extending across the room, embody an existence, positioned on the threshold between nature and technology. In their arrangement relative to one another, the sculptures suggest safety, hospitality, but also confrontation.

The formation is encircled by the work series Ghost forest 1–7, 2024, cast on the walls like shadows or spectral traces of trees. In this way, the series points the way to other areas of the exhibition, but also allows a glimpse beyond the physical boundaries of the gallery space, facilitating the perception of an invisible yet present dimension of past times. Inspired by subtle remnants of the past—archaeological imprints and the other-worldly presence of ghost forests—they emphasize that time leaves its mark on all things. Thus, they remind us that every being, every structure, and every landscape leaves behind an echo that continuously shapes and defines our world.

Central to Mujinga’s exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel is her deep engagement with the concept of bearing witness as an act of resilience. How can accumulated experiences form a protective shield that enhances resistance? In many societies, elders serve as living libraries, preserving and transmitting histories and traditions through storytelling and communal exchange. This process of sharing experiences across generations continuously shapes collective memory. In the first room, Mujinga’s “singing trees” exemplify this concept, emitting singing of a choir from their crowns. Filling the gallery space with various voices, tones, and pauses creates an immersive interplay of shared memories. These voices, which can sometimes synchronize arbitrarily, evoke communication among the trees as witnesses to historical transformations as well as to the echoes of climate change and conflicts.

New technologies have enabled the development of flawless, synthetic voices that can replicate human and posthuman sounds with precision.

In contrast to the perfection of voice cloning, Mujinga’s installation Time as a shield, 2024, features a choir of human voices that intentionally preserves imperfections, like trembling and fluctuations of the voice, or vibrations of the breath. Created with recordings and compositions from seven singers, it blends solo voices with syncopated moments and pauses of silence. By embracing these imperfections, the artist acts as an archivist, preserving and celebrating the uniquely human aspects of voice and expression. This approach explores how the collective voice can offer protection and empowerment to individuals, presenting a stark contrast to the sterile perfection of AIgenerated sounds. Mujinga’s new body of work also critically engages with contemporary technologies and their impact on surveillance and control. The artist, inspired by Achille Mbembe’s theory of necropolitics, scrutinizes methods of population control via exposure to death—whether through war, environmental destruction, or poverty. Mbembe’s concept, which builds on the French philosopher Michel Foucault’s idea of biopower, addresses how these forces exert control over individuals by systematically exposing them to death. In her search for new survival strategies, Mujinga responds to these issues by having the voices in the sound installation act as a counterforce to necropolitical control. The choir embodies a form of collective resistance that stands against obliteration. Whether in harmony or not, each voice symbolizes a distinct existence that defies silence. The chorus becomes representative of the power of community, withstanding the isolation and dehumanizing aspects of necropolitics.

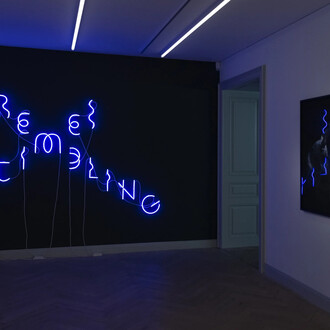

In the second room, Mujinga’s new photographic series Shared breath (1–6), 2024, extends her exploration of identity and protection. Featuring six portraits that initially appear to depict the same person, upon closer inspection, the series reveals subtle differences. Amid the rise of deepfakes in our online interactions, she uses digital tools to blend and transform portraits of friends and family, creating entirely “new faces.” Instead of seeking perfect replication, she highlights the irregularities and glitches that expose the composite nature of the images. The work in this series is not merely about the technology itself, but about imagining a world where we might use such technology voluntarily, “borrowing” and altering each other’s faces within a community as a form of mutual protection and solidarity.

However, Mujinga is also keenly aware of the social, political, and economic implications of these technologies. Her work addresses the racial biases embedded in facial recognition systems, which frequently misidentify or fail to detect darker skin tones at all. In this context, face-sharing therefore not only aims to evade surveillance but also challenges the systemic biases embedded in our technological infrastructure.

The perception of existing in darkness is a recurring motif in Mujinga’s work. Dark green light, reminiscent of a green screen that can become anything, embodying both absence and presence, has illuminated her human-like sculptures in past shows. In the final room, a figure in transition stands with a trunk-like body and missing arms, gradually transforming into a tree-like form. Grief, 2024, draped with textile skin made from handsewn upcycled fabrics, ties it to Mujinga’s broader exploration of textiles as both surface and potential habitation.Its isolated form, lacking the vocal element ofthe other sculptures, reflects the oftensolitary nature of grieving. Yet, when viewed within the context of the entire show, it emphasizes the potentialfor community support in the shadow of systematic mourning. The figure invites the viewer to consider how grief reshapes identities and connections in an increasingly digital world, where memories and presences persist in unconventional forms.

Through the lens of science fiction, Mujinga creates alternative worlds, reimagining new futures while preserving echoes of the past. Her artistic practice aims to dissolve conventional boundaries, offering new perspectives on existence and identity. This approach aligns with her broader goal of challenging dominant ideologies and proposing innovative ways of understanding the world. Conceptually, Time as a shield underscores the need for community and resistance, proposing new ways to engage with and understand a rapidly changing world. In Mujinga’s work, the overlap and interplay of voices and individual bodies creates a narrative that celebrates both individuality and togetherness, reminding us that, even in times of threat and control, the presence of voices remains a powerful tool for survival and change.