Perrotin is delighted to present Emma Webster’s first solo exhibition in Paris, The engine of beasts. In her third show with Perrotin, Webster stages paintings alongside sculptures, so viewers may follow the representation of a beast in all its states. The guiding theme of the exhibition: The word Engine’s Latin etymon, ingenium, meaning skill or ruse, also signifies the ability to move easily from one medium to another, like a life-form striving to adapt, evolve, and survive. Between the transfiguration and fictive landscapes that serve as a barrier between the characters and the viewers, Webster reveals her interest in sentience, a combination of sentiment, sensation, and conscience.

Virtual reality? Real virtuality: the ruses of Emma Webster

The fox is lost in the darkness of the painting, and so are we. Something seems to catch his attention–he has just barely paused his movement. Crafty is part of a long tradition of animal painting: it is reassuring, as is the chosen technique, oil on canvas, which has been considered the most prestigious in the West for centuries. But soon various elements of this exhibition in Emmanuel Perrotin’s Paris gallery begin to disturb us. Some of them are related to the paintings themselves, and others are the result of the overall exhibition design.

These paintings make us reflect on the separation between humans and animals, as with any representation of an animal, whether it feels familiar or quite distant. In Emma Webster’s work, distance dominates. The animals appear solitary or in pairs within a landscape where humans have left no trace. The light is often limited, and the ground is emphasized, as with the lamb in Witness. But the very title of this painting draws our attention to another feature: the fact that the animal figure seems to perceive a presence that is invisible to us. A threatening mood recurs in these paintings, a sense that something could happen and cause physical harm.

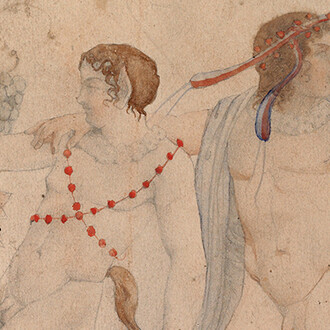

This is true also in the way the creatures are depicted. In fact, as soon as we examine the artworks more closely, we realize that something is wrong–meaning that Western conventions are both present and challenged. The figures in the paintings are sometimes treated “realistically”. Then, on the contrary, in the representation of the fox mentioned above, in Bovine skull, and even more so in Great poet! (which is prominently displayed in a central location in the gallery), we can clearly see that the figure is made up of a corroding ligature, or something that may be a metal structure. In any case, it is not a real body.

It suddenly becomes clear: this nature is fictitious. These animals, the same ones who embody an immediate relationship to the world quite distinct from our mental games, are not part of a reality that would reassure us. Clues start to appear, starting with the landscape, which recalls the kind of fantasy world seen in many popular forms of art, movies, or video games. And then there’s this strange light–not the kind we usually see in paintings, coming from a single source from the upper left of the canvas, participating in the unification of the fictive space that has been so important for centuries, an ambient lux as opposed to an artificial and partial lumen. Here, each element seems to contain its own lumen, preventing the unification of this world.

So we have caught the artist: Emma Webster makes art using VR or “virtual reality”, i.e., software to create 3D images. The artwork becomes an intermediate site. In this exhibition, Webster takes this approach quite far. A fox sketched in charcoal serves as the matrix for a 3D version that is produced as a sculpture and serves as a model for a painting. Are we being deceived? There’s no deception, because we can see the artifice, whether these are manifestly hybrid monsters, such as Great poet!, or figures composed of juxtaposed armatures, like Bovine skull. Yet our interest in the unknown world of these beasts is not affected, for they evoke a recurring problem in Western philosophy: what is the world outside one’s perception? For instance, what is the world of animals? Emma Webster has mentioned her interest in contemporary thinking about animal consciousness, which is often defined today as “sentience”, a combination of sentiment, sensation, and awareness. And, as for many of her generation, coincides with an overall awareness of the environmental crisis. In this way, the empty landscape could be interpreted as the representation of a world before or after a disaster has wiped humans off the face of the earth. But even without assuming such a fateful scenario, there remains simply the respect for a world that is no longer anthropocentric.

So if the artwork is both true and false, if it is the result of a complex interplay between mediums and levels of reality, what truly counts is the experience–the relationship to the artwork. Emma Webster is not afraid to shock: in the first room, viewers encounter five large artworks, each measuring over three meters. This arrangement recalls panoramas–all-encompassing popular paintings that had their hour of glory in the nineteenth century. “Glory” is the right word, because they were especially focused on battles. But here, the artworks capture anonymity, the simplicity of the perpetuation of life. A perpetuation that can only be observed. The issue of perspective is crucial, because these animals are almost never viewed straight-on, but seen centrally or laterally, or from a high or low angle.

And the boundaries of the paintings are explored, especially through the dissociation between the figure and the background. This occurs with the shadow of the main figure in Great poet! and especially in The Address: the sheep is placed before what looks like a canvas within the canvas–a painting depicting the landscape. The exhibition as a whole also plays with the limits of the artwork by placing paintings alongside sculptures. In this way, we can follow the representation of the fox in all his states (in keeping, as we have seen, with a creative process that allows him to be used in various contexts). The stage of the bas-relief is particularly important, because in Western art history it is the purest form of the interplay between two and three dimensions. Here, in Saxon fawn, this interplay takes on a disturbing form: the animal seems to be underneath a kind of translucent plastic sheet that encloses it. The threshold has been closed off.

Le silence des bêtes (the silence of the beasts). This is the wonderful title of a book by Elisabeth de Fontenay, a major work on animals in Western philosophy. Mute painting or sculpture are part of this world of silence. Yet sounds are heard in Webster’s work–sounds that come from her surprising titles. Why Grum, evoking a growl or grunt, for the ram’s head? Its reputation for having a bad character? This is a sign of the artist’s sense of humor, which, acknowledging the cliché, we might trace to a tongue-in-cheek attitude from her British roots. But this is also a new kind of mimesis, an imitation which is now called transmogrification, the manipulation of appearances permitted by VR, which the painter– who is voluntarily limited to a fixed medium, determining a single point of view corresponding to a single narrative moment–accepts.

Behind this, there is another image that is expressed in the title of the exhibition: The engine of beasts. We can interpret this as the evocation of a new kind of mechanism at two levels. The engine within the animal, in the way that Descartes expressed it. The rendering engine, the software that improves the realism of the images, Blender–once again, form and content are closely associated. But we may also sense something expressed by the recurring presence of the fox, the real guiding theme of the exhibition. The word engine’s Latin etymon, ingenium, meaning skill or ruse, also signifies the ability to move easily from one medium to another, like a life-form striving to adapt, evolve, and survive. Thanks to art, tso inventiveness. Indeed, the Old French verb eng(e)ignier means “to imagine” or “to invent”, “to produce with art and technique”, but also “to deceive”.

As we see in this exhibition, Emma Webster proposes a beautiful and powerful reflection on the art of representation in the West, fearlessly integrating virtuality to express this new reality composed of so many layers of combined images and bodies. But her work echoes a centuries-old reflection by Guillaume de la Perrière who wrote Théâtre des bons engins in 1535. These were not engines, but reflections on humanity. Today, in Emma Webster’s work, these reflections concern an expanded world where humans and animals, nature and artifice, and art and thought are inevitably associated.

(Text by Etienne Jollet, art historian, professor at the University of Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne)