Urbanism works when it creates a journey as desirable as the destination.

Paul Goldberger (Frederick & Mehta, 2018)

Cities not only have the ability to shift path dependencies but also to disrupt business-as-usual models to reduce environmental impacts and restore ecosystems. Cities provide platforms for more inclusive, publicly engaged decision making thereby challenging the current systems of distribution, recognition, and participation. At the same time, however, cities are constrained by the short-termism present in most political systems that favor existing power structures and immediate political wins (e.g., employment opportunities in carbon-intensive industries) at the expense of long-term transformation processes. However, many examples exist where cities have been successful in addressing capacity constraints and governance barriers, thereby taking steps towards environmentally sustainable and just transformations.

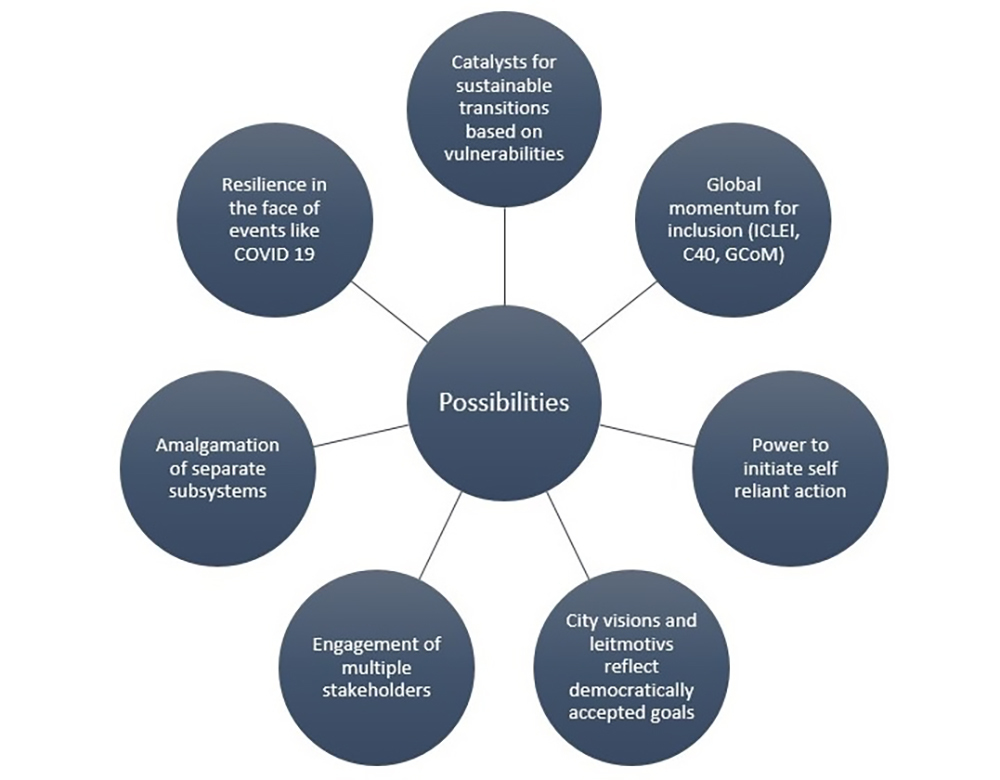

Accordingly, this essay will highlight both the possibilities and limitations of cities as promising agents of sustainable and just practices with the help of relevant examples from all over the world. Drawing on transition research which provides explanations to questions of large-scale societal change in multiple contexts depending upon the subject of transition along with the mechanisms and drivers that have the highest explanatory value (Loorbach, Frantzeskaki & Avelino, 2017), the essay will focus on the role of governance and agency with cities as referent objects in bringing about societal transformation.

Cities as agents of change

The importance of the local context in advancing more sustainable and just practices cannot be denied for several reasons. First, the relationship between cities and the environment is like a double-edged sword. On the one hand, citizens’ lifestyles and infrastructures both positively and negatively impact the natural environment within and outside their political jurisdictions and boundaries. On the other hand, cities themselves are not immune to external shocks, natural hazards, and environmental degradation. Urban areas account for around 70% of total human-induced emissions, three-quarters of which come from energy consumption (Stobbelaar, van der Knaap & Spijker, 2022).

Moreover, by 2050, 68% of the world’s total population will be living in urban areas, whereby cities will lose their green spaces, levels of biodiversity, and the natural environment (ibid.). Such rapid urbanization will also adversely affect human health and standards of living. Hence, it is important for cities to be the frontrunners of sustainable transitions, and a rise in the number of cities that have pledged commitments to climate change and who have documented actions towards these ends has led to a strong belief that action is and can be taken in the right direction.

For instance, the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy has become the largest global alliance for city climate leadership, representing 11,812 cities that account for about 1.039 billion people in the world. Similar initiatives also exist in the form of Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI), the Global Task Force, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40), and the nature-focused CitiesWithNature that provide integrated and enabling platforms to inspire cities to make groundbreaking efforts towards a more sustainable shared urban future.

Second, in some jurisdictions, cities have the power to initiate self-reliant action in the pursuance of new and innovative local development strategies. In such cities, e.g., Oslo (Green Capital of Europe 2019) or Rotterdam (Carbon neutral port until 2050), governments and the mayor play key decision-making roles and act as channels of communication to bring about acceptance for a more just and sustainable transition (Kabisch et al., 2019). Oslo’s strategy for future development enshrined in its Municipal Master Plan “Oslo Towards 2030: Smart, Safe, and Green” to bring about sustainable transitions are glaring examples of the power which cities have in shaping sustainable transitions (Kristjánsdóttir, 2018).

Third, some city visions and leitmotifs encompass the broad democratically accepted goal arrangements based on or leading to citizens’ involvement, thereby bringing about positive change. Such images move beyond a simple description of the city’s strengths like history, architecture, or scenic beauty and even basic topographical attributes like location near the sea or mountains to imply a normative understanding of what the city wants to become and achieve. For example, Rotterdam’s energy transition towards becoming a carbon-neutral port brings with it the required momentum to realize this dream (Port of Rotterdam Authority working with businesses in the port).

Fourth, local contexts ensure the engagement of multiple stakeholders such as citizens, grassroots organizations, (in)formal groups, and charismatic leaders by providing a platform that ultimately leads to concrete action. For example, the Pakistan Sustainable Development Goals and Community Development Program (2014) brought together public sector agencies, provincial and district governments, the National Technical Committee, along with district counselors and people within these cities and districts to identify issue areas within their vicinity for immediate action (Cheema et al., 2021).

Fifth, cities have the ability to bring about a multiple-system transformation whereby many separate subsystems (green urban infrastructure, housing, transport, climate-related issues, etc.) come together and change simultaneously in relation to each other. For instance, the city of Utrecht plans to construct 60,000 houses along with 70 hectares of green area within its existing city boundaries in the upcoming twenty years (Stobbelaar, van der Knaap & Spijker, 2022). This vision is being realized by reducing the space for mobility (limiting the presence of cars) and encouraging green urban infrastructure—a combination of housing, transport, urban green area, and livability. Another example of a cross-sector governance model is the United Kingdom’s Greater Manchester Low Carbon Hub put forth by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority to develop a long-term vision for carbon neutrality by 2038 with intersections between various subsystems (Greater Manchester Combined Authority, 2022).

Sixth, the nature of and responses to the global COVID-19 pandemic provided important lessons regarding the potential which cities and the larger urban world have and manifested in the face of a dynamic and unpredictable future. A global threat like that called for multilateral cooperation and multilevel governance complementing national and local efforts. It reinforced the notion that well-planned cities were better able to manage the contagion by recognizing the socio-economic, political, and built environment factors that exacerbated vulnerabilities and by promoting socio-spatial equity (Krellenberg & Koch, 2021). For example, San Francisco introduced the Slow Streets program (2020) during the pandemic to provide residents safe spaces to walk, bike, and socially distance by closing 31 streets to traffic.

Lastly, although cities are quite diverse in nature and one varies from the other based on its culture, economy, environment, infrastructure, and history, key linkages between them still exist that account for their unsustainable practices, such as the prevalence of an interest-based static political economy, the supremacy of business-as-usual models of urban planning geared towards exploiting nature, and the complex governance systems in which cities are embedded in that slow transformational progress. Since the complex interplay between human systems and built environments shapes cities, it also provides entry points for transformation in a just and sustainable manner.

For example, the Ruhr region in Germany was a former industrial hub focusing on coal and steel production. The area was characterized by a very low standard of living, rampant environmental degradation, and a predominantly illiterate population. The 84-km-long Emscher River, which flew through the heart of the region, was used as an open sewer (Franz, Güles & Prey; 2008). Once the coal mines and the steel industry were shut down, large patches of infrastructure and land became worthless, unemployment grew, and so the inhabitants of the area migrated to other parts of the country (Ibid.). Moreover, the polycentric nature of the area with different levels of development and very little understanding of conservation by the public combined with other challenges mentioned above gave the area an overall grim look.

Today, the Ruhr area is characterized by an extraordinary industrial legacy, revitalized brownfields, big parks, and green spaces that have made it a leading example of the process of renaturation, conservation, and instrumentalization of ecological functions (Gerner et al., 2018). The state of the Ruhr region as described above provided a great opportunity for transformation whereby, with the participation of different stakeholders like the Ruhr administration, Emscher Association, locals, etc., urban spaces were reused, the river was cleaned up, and a model region was developed in the wake of the former coal and steel industry.

Figure 1. Potential of cities in bringing about sustainable and just transformations.

Limitations of cities as change agents

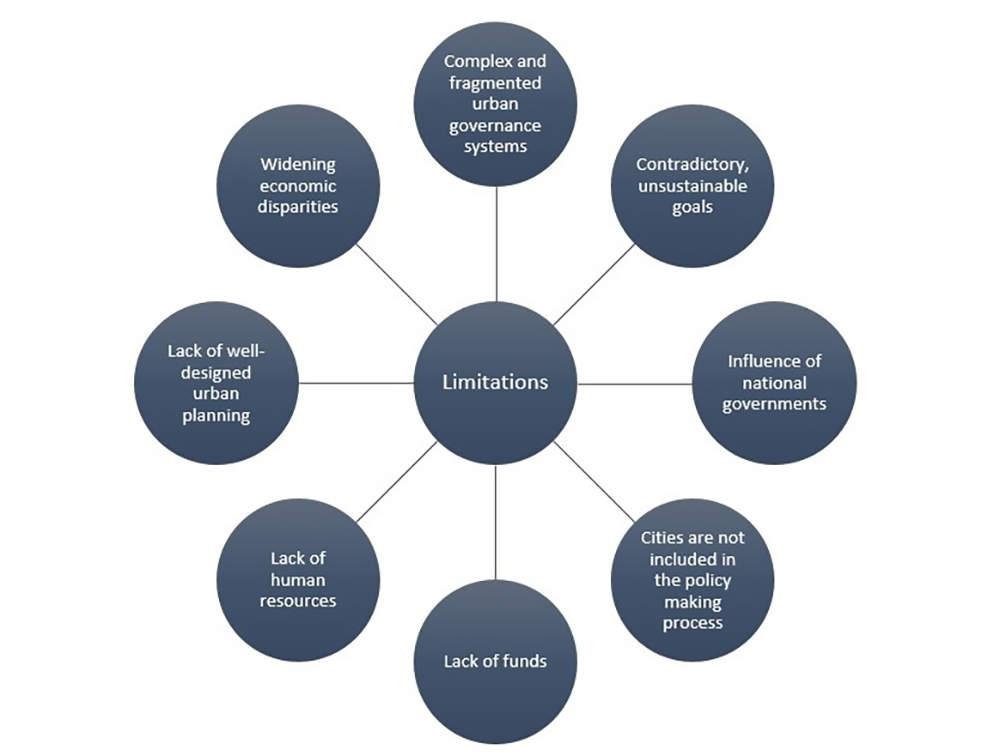

Cities have the potential to act as catalysts for environmentally sustainable and inclusive development, and as the discussion above showed, interventions at the local level are extremely important for sustainable transformation, not just at the city level but at the national and global levels as well. However, in a bid to bring about such lasting change, cities are also constrained by several factors. In this regard, one major issue is the presence of a complex and fragmented urban governance system which hinders a low-carbon, climate-resilient urban transition necessary for achieving national and globally set goals and commitments.

Cities are governed by a wide range of institutions and policy instruments both within and beyond their boundaries that either may have contradictory and unsustainable goals or unclear and limited mandates to subnational governments. Although leaders within the urban setting can initiate new projects geared towards improving the planning and functioning of their cities, national governments can impact progress to a significant degree. In this manner, centralized national policies can reinforce environmentally unsustainable business-as-usual trajectories at the local levels with the provision of no alternatives (Linnér & Wibeck, 2021). For example, cities reliant on national/regional fossil fuel-based energy systems will end up emitting high emissions since they are constrained by the broader governance and institutional frameworks to self-generate and provide clean energy (Aylett, 2013).

In addition to the challenges posed by multiple levels of governance, problems also exist at the city level itself. For example, implementation at the city level is crucial for meeting major international commitments such as the Sustainable Development Goals or the Diversity and Nationally Determined Contributions for the Paris Agreement on Climate Change; however, cities are seldom engaged and empowered to chalk out implementation strategies, secure funding options, and provide additional capacity required to realize national priorities. This can prove to be troublesome for African and Asian medium-income cities that will see the greatest influx of people in the coming years (Wolfram, Frantzeskaki & Maschmeyer, 2016). The lack of basic services, housing, and health care coupled with the impacts of natural hazards and extreme weather events will result in major catastrophes (ibid.)

Similarly, even large, and capable city governments lack funds to carry out environmentally responsible public projects since they are dependent upon centrally allocated funds earmarked for urban development, which are prioritized with respect to the broader national development plans. Sometimes decentralized governance systems where municipalities have significant power, such as in India or other countries which are in the process of decentralization such as Kenya, are unable to bring forth improved city action due to the availability of limited financial resources and concrete mandates to raise funds for innovative projects. Severe resource constraints, including paucity of both skilled and unskilled human resources and well-designed business plans mean that cities are not able to bring about cutting-edge, socially just, and environmentally sustainable transformations.

The Indian Smart Cities Project provides a good example of how the above-mentioned problems can impede sustainable transitions. The Smart Cities Mission in India picked 100 cities, housing 21% of the total Indian population, to make them more livable, environmentally sustainable, and economically viable by developing core infrastructure and services within a period of 5 years (Singh & Parmar, 2020). To implement the project, the Indian Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs empowered the cities to constitute a special purpose vehicle (SPV) consisting of a chief executive officer and nominees of the central, state, and local governments with funding from several sources (ibid.)

Today, more than 50% of the projects remain unfinished even after the 5-year period has elapsed, the major reasons being mismanagement and lack of finances. Since each SVP was responsible for its own jurisdiction, no uniform pattern of development was followed, and so priority was given to elitist interests. Similarly, there were audit violations, inadequate understanding/analysis of data, and a lack of coordination between multiple government departments. Also, funds were not mobilized to the SVPs in time since multiple sources were involved and the SVPs themselves were not functioning efficiently (ibid.) Hence, this project serves as an example of the constraints which cities face with regard to funding and expertise because of which sustainable transformations are not materialized.

Figure 2 Limitations of cities in bringing about sustainable and just transformations.

Conclusion

The essay highlighted the potential and limitations of cities in transforming their own environments and societies while also impacting places beyond their immediate urban environment, illustrated with the help of examples from all over the world. Although the importance of cities in the realm of multilevel governance cannot be denied, cities need to play a larger role in providing solutions to problems of environmental sustainability and social justice. Depending on the context in which cities operate, they can do so by making governance processes more inclusive and publicly engaging. Moreover, urban planning and city management should also factor in the complexity and diversity within and beyond cities so that business as usual modes of exploitation can be changed. Furthermore, cities should achieve deep decarbonization, build urban circularity, and support social inclusion and justice so that pathways towards environmentally sustainable and just outcomes can be realized. Based on the discussion above, it is concluded that overall, a successful restructuring of the fundamental processes of governance can not only be achieved but also sustained in the long run, as summarized in the figure below.

Bibliography

Aylett, A. (2013). The Socio-institutional Dynamics of Urban Climate Governance: A Comparative Analysis of Innovation and Change in Durban (KZN, South Africa) and Portland (OR, USA). Urban Studies, 50(7), 1386-1402. doi: 10.1177/0042098013480968.

Cheema, A.R., Kemal, M., Ahmed, N. & Hassan, H., (2021). Pakistan SDGs Status Report. Federal SDGs Support Unit, Islamabad, Ministry of Planning, Development and Special Initiatives, Government of Pakistan.

Franz, M., Güles, O., & Prey, G. (2008). Place-Making And ‘Green’ Reuses Of Brownfields In The Ruhr. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 99(3), 316-328. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2008.00464.xGruehn, D. (2017). Regional Planning and Projects in the Ruhr. In M. Yokohari, A. Murakami, Y. Hara, & K. Tsuchiya, Sustainable Landscape Planning in Selected Urban Regions (pp. 215-225). Japan: Springer.

Frederick, M., & Mehta, V. (2018). 101 Things I Learned in Urban Design School (1st ed., p. 16). New York: Three Rivers Press.

Gerner, N., Nafo, I., Winking, C., Wencki, K., Strehl, C., & Wortberg, T. et al. (2018). Large-scale river restoration pays off: A case study of ecosystem service valuation for the Emscher restoration generation project. Ecosystem Services, 30, 327-338. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.03.020.

Greater Manchester Combined Authority. (2022). Low Carbon Hub Board (pp. 1-4). Manchester: GMCA.

Kabisch, S., Finnveden, G., Kratochvil, P., Sendi, R., Smagacz-Poziemska, M., Matos, R., & Bylund, J. (2019). New Urban Transitions towards Sustainability: Addressing SDG challenges (Research and Implementation Tasks and Topics from the Perspective of the Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) of the Joint Programming Initiative (JPI) Urban Europe). Sustainability, 11(8), 22-42. doi: 10.3390/su11082242.

Krellenberg, K., & Koch, F. (2021). Conceptualizing Interactions between SDGs and Urban Sustainability Transformations in Covid-19 Times. Politics And Governance, 9(1), 200-210. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i1.3607.

Kristjánsdóttir, S. (2018). Nordic experiences of sustainable planning (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

Linnér, B., & Wibeck, V. (2021). Drivers of sustainability transformations: leverage points, contexts and conjunctures. Sustainability Science, 16(3), 889-900. doi: 10.1007/s11625-021-00957-4.

Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599-626. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340.

Singh, B., & Parmar, M. (2020). Smart City in India: Urban Laboratory, Paradigm or Trajectory? (1st ed., pp. 10-25). New York: Routledge.

Stobbelaar, D., van der Knaap, W., & Spijker, J. (2022). Transformation towards Green Cities: Key Conditions to Accelerate Change. Sustainability, 14(11), 6410. doi: 10.3390/su14116410.

Wolfram, M., Frantzeskaki, N., & Maschmeyer, S. (2016). Cities, systems and sustainability: status and perspectives of research on urban transformations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 22, 18-25. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.014.