The 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the critical significance of human settlements. In fact, the Declaration spells out in Article 25 what human settlements entails, what are the rights that define and are associated with this sector of society. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights categorically states that everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself/herself and of his/her family, including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and necessary social services.1 The right further extends to provision of social security and safety nets in cases and situations of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond ones’ control.

The rights and services encompassed in the Universal Declaration can be arguably summed up and collectively referred to as everyone’s right to human dignity. Therefore, human settlements is about both promoting and protecting the right to human dignity. However, it was only in Vancouver, Canada, on 31 May to 11 June 1976, that the nations of the world, for the first time, came together to engage in a multilateral discourse on comprehensive human settlements agenda. The conference became famously known as Habitat I. The rationale behind the conference was the recognition of the impact of rapid urbanisation and its impact on sustainable human settlements in urban areas, towns and in the cities. The developing countries were and still are the ones affected the most by rapid urbanisation and its impact on human settlements public services such as housing, water, sanitation, education, and health. In 1976, human settlements, particularly urbanisation, was neither one of the priorities of the international organisations such as the United Nations, nor featured prominently in the global development agenda.

Shared developing countries’ challenges experienced in 1976 are still strikingly present today, these include inequalities in standards and living conditions of the people, the poor being the worst off. Social segregation and racial discrimination which were witnessed in countries like South Africa, Namibia, and other parts of the world, including in Latin America where people of African descent were forced to settle in peripheral areas, far removed from the cities and centres of economic activity, remain a characteristic feature of the major cities in these countries. Thus, such spatial arrangements contributed to social challenges such as acute poverty, rising unemployment, spread of disease and malnutrition due to lack of food, adequate healthcare and medical centres, strained race-relations, and complete erosion of social cohesion.

Forty-eight years ago, it was some of the above challenges that brought the United Nations Member States together to explore options on how to collectively and collaboratively deal with them. In the Vancouver Declaration, a global agenda was set for human settlements from which subsequent developments, resolutions, and institutions were set in motion. The Declaration called for human settlements governance at national and international levels, which prioritised: (a) taking bold, meaningful, and effective human settlements policies and spatial planning strategies realistically adapted to local conditions; (b) creating more liveable, attractive, and efficient settlements which recognise human scale, the heritage, and culture of people and the special needs of disadvantaged groups especially children, women, and the infirm in order to ensure the provision of health, services, education, food, and employment within a framework of social justice; (c) creating possibilities for effective participation by all people in the planning, building, and management of their human settlements.1

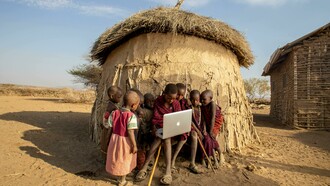

The 1976, Declaration further states that governments and international partners have to work together in (d) developing innovative approaches in formulating and implementing settlement programmes through more appropriate use of science and technology and adequate national and international financing; (e) utilising the most effective means of communications for the exchange of knowledge and experience in the field of human settlements; (f) strengthening bonds of international co-operation both regionally and globally; (g) creating economic opportunities conducive to full employment, under healthy, safe conditions, where women and men (to which it could be added other recently recognised genders) will be fairly compensated for their labour in monetary, health, and other personal benefits.1 In meeting this challenge, human settlements must be seen as an instrument and object of development. The goals of settlement policies are inseparable from the goals of every sector of social and economic life. The solutions to the problems of human settlements must therefore be conceived as an integral part of the development process of individual nations and the world community.2

Subsequent international engagements were held to follow-up and expand the scope of activities and policy interventions on human settlements development. Some of these are Habitat II-III, the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development, the Sustainable Development Goals (also known as Agenda 2030), the New Urban Agenda, Global Action Plan on Accelerated Transformation of Informal Settlements and Slums, in Africa there is Agenda 2063, to mention but a few. In 2023, the United Nations (UN) agencies reported that around 56% of the world’s population, which is 4.5 billion people, live in cities. The UN agencies further stated that 80 million people are added to the urban population every year, and the figure is set to surge closer to 60% by 2030 and will likely reach 70% by mid-century. Furthermore, 90% of this growth will take place in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Concerning in the trend described above is that rapid urbanisation is largely unplanned, unmanaged, and unregulated. Consequently, developmental challenges such as environmental impact, socio-economic issues, inexorable rural-urban migration, spatial challenges, etc., put pressure on governance and service delivery. According to the United Nations, the population of slum dwellers has surpassed 1 billion and is rising with the largest proportions of slum dwellers living in Asia and Africa. Human settlement is an integral part component of human security. The latter is more concerned with guaranteeing people’s freedom, rights, and protection against harm and health hazards. Therefore, the challenges and delays in addressing human settlements needs of the people exposes them to life threatening risks such as natural and climate change disasters, rapid spread of diseases in highly populated, and dense informal settlements.

Recent reports on the performance of the world regarding the implementation and achievement of the targets set out in the Sustainable Development Goals set in 2015, indicate that the world is lagging behind on some targets, including SDG 11 which deals with building cities and human settlements that are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. The UN agencies dedicated to the social development issues through capacity building support to governments and non-governmental organisations, reported that between 2014 and 2020, the total number of people living in slums and slum-like conditions slightly declined from 25.4 per cent to 24.2 per cent. However, only a fraction of this population, which is estimated to be at 1 billion, has access to basic services such as consistent supply of clean water, sanitation, education, healthcare, and roads infrastructure. Clearly by 2030, which is slightly more than six years away, the social and living conditions that prevailed in 1976 would still be prevalent more than half a century on.

Given the current global trends characterised by rapid technological advancement and artificial intelligence, which among other negative impacts, displaces people (especially those who are unskilled or lowly-skilled) from their full-time employment, growing impact of climate change and disaster-prone areas, land tenure issues, and the vestiges of colonial and apartheid land policies in some developing countries, a fundamentally radical paradigm shift is required. That paradigm shift ought to be comprehensive, responsive, intentional, and deliberate in addressing human settlements development agenda which was set more than four decades ago.

Urbanisation, which is the key driver of human settlements challenges in cities and towns, particularly in informal settlements, has to be managed through participatory governance systems. Government authorities and the communities have to be equal stakeholders in both policy formulation and implementation. A top-down traditional approach in town and urban planning is outdated and has to be urgently done away with. A collective planning and governance model has to be developed and implemented at local level. An indisputable fact is that what constitutes a global or international problem or challenge emanates from local causes and conditions. Hence, the solution has to be locally grounded even it is influenced or shaped by international best practices.

People know their immediate challenges and basic needs. Therefore, governments must set priorities and fund programmes that are collectively developed and adopted with communities. The era of prioritising provision of services that generate revenue for the local authorities at the expense of addressing the pressing and immediate needs such as basic infrastructure and services is over. Urbanisation, as much as it creates opportunities for companies to access excess labour in close proximity to the cities, also creates opportunities for the development of secondary and intermediate cities that can accommodate population overflows from the big cities. This, however, should not be done as an emergency management measure, but as a policy priority to enhance improved and modernised urban and spatial planning.

Rural development seems to be almost always left out of the equation insofar as the development of human settlements is concerned. The major advantage of the rural areas, which paradoxically is the shortcoming in the urban areas, is that adequate land is available which can be utilised to build modern government service centres, intensify agricultural and related industries economic activities, and the effects of climate change are not as acute as they are in urban areas. Rural areas are not as densely populated as urban areas, though that is a challenge in relation to the provision of bulk services, it is also an advantage in preventing other disasters such as shack or slum fires, rapid spread of airborne diseases, etc. Pollution and unmanaged waste that are widespread in urban areas are a rarity in rural areas, affording the residents better chances of leading healthier lives, provided they can also be supported with more economic and developmental opportunities.

The 2023/24 Human Development Index Report entitled “Breaking the Gridlock” makes a conclusion that the global community is falling short in meeting the development needs and in providing global public goods whether it is on education, health, housing, climate change mitigation, generally in improving the standards of living. Inequalities between countries at the top of the index and those at the bottom are widening. The report further argues in no uncertain terms that the path of human development progress shifted downwards and is now below the pre-2019 trend, threatening to entrench permanent losses in human development.2 Gradual progress was registered pre 2019 for a period of two decades and that has now been reversed by global challenges such as climate change, economic inequalities, political instability, etc. Competition seems to be triumphant over cooperation, both at national and international levels. Therefore, it stands to reason that something ought to change in how countries interact with each other on development issues and how the outcome, decisions, and resolutions find expression in national and local policies and programmes.

What ought to be done to accelerate pace in the delivery of sustainable human settlements? Firstly, empowerment of the people of the deal and manage their local challenges is key. Governments in developing countries should train local residents to enhance their skills set, whether it is artisanal, vocational, or specialised careers. Secondly, decentralisation of governance powers to the local authorities cannot be overemphasised. Local authorities are in the coal face of people’s daily struggles. Thus, it is needless to state that more financial and human resources, including expertise, should be deployed to the sphere of government that is at the operational level. It is doesn’t help advance any developmental cause to have glossy policy blueprints which have no practical meaning nor resonance with the basic needs of the people where they lead their lives on daily basis. Thirdly, social cohesion and nation building are underlying pillars of social development. Residents ought to be conscientised on fundamental values and principles of good citizenship.

The 2023/24 Human Development Index Report offers a succinct definition of social cohesion, that it is the vertical and horizontal relations among members of society and the state that hold society together. Social cohesion is characterised by a set of attitudes and behavioural manifestations that includes trust, an inclusive identity, and cooperation for the common good.2 People must be encouraged to develop and contribute to a culture of carrying for one another, as the English poet John Donne taught us, ‘no man is an island’, that is none among us is adequately self-sufficient, we always need one another one way or the other. In South Africa, the spirit of Ubuntu, which means 'I am because you are', must in honesty and truth, be a driving force in building and implementing social contracts between the government and the governed.

Notes

1 United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 2024.

2 United Nations, Human Development Report 2023/2024, 2024.