Felicity Nussbaum, in her critique of the poem, argues there is no single theme that unifies the poem, suggesting various ideas are repeated. Martha becomes the embodiment of eighteenth-century conduct book expectations for women: good humor, sense, social love, and a quiet, unassuming wit. Compared to other women who are imposters with assumed identities, she is presented as genuine. In contrast are the portraits of the women condemned by society for being fickle, inconsistent, excessive self-love, and ostentatious displays of wit. These attributes were condemned as a self-centered approach, as they could be seen as challenging men’s positions in an effort to outshine them. Wit was associated with immorality due to the prejudice against women learning, as when taken to extremes, it could make them violent, quarrelsome, and destructive of the social order. James Fordyce stated that women who sought knowledge looked for control and power. His solution was they should confine themselves to the domestic sphere.

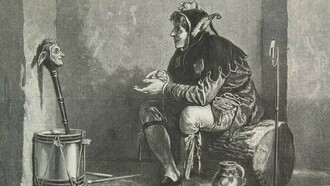

Martha and the poet take a tour of the portrait gallery, which frames women in various situations and poses:

- Narcissa scorns good nature. Thus, when she reads a book on martyrs, it is regarded as suspect, as she violently alternates between religion and atheism.

- Flavia exhibits excessive quickness and spirit. She rages and whirls into impotence, where virtue in excess turns to vice.

- Atossa has a furious and violent passion. Her social relations are self-centered and, when turned inward, result in self-importance. She exhibits false wit with furious and powerless arrogance, affection, and misplaced piety. Therefore, Pope associates wit with scandal, and her rage threatens subversive force and is undermined by her own spirit and desire.

- Cloe is apathetic and incapable of generosity and love.

- Silia’s kindness abruptly turns into raving.

- Philomede is chaste to her husband. She is described as immorally fertile but empty indicating an inability to fulfil a woman’s role. She has artificial learning along with inflated public affection.

- Arcadia’s Countess demonstrates extravagant foolishness.

- Rufa reading Locke is a study in disproportion.

- Calypso is dangerous and cunning, producing uneasiness due to her bewitching tongue.

- Queen’s naked vice hides beneath her garments.

Pope shows that the women portrayed have desires that cannot be fulfilled and a pleasure which consumes itself from the inside out. He states that a woman’s ruling passion is pleasure, and this manifests in a thirst for power. There is a lack of self-control, which the Stoics referred to as a virtue, implying these women are not virtuous. These women assert their own desires by objecting to the idea of defining women as mere objects of male desire.

Martha, in contrast, represents the ideal woman. She also stands for the female audience, who are convinced of the immorality of the portraits and, as such, are engaged on the side of the male speaker. As an ideal woman, she has rid herself of the ruling passions, power, and pleasure which plague female sex. She is a fusion of charm, vanity, and the energy of female passion, along with the stability, directness, and strength of masculine reason. Her charm and modesty are contrasted with other women’s vanity and the pursuit of pleasure. The poem praises her senses and good humour, with enduring fame as her reward. Where sense is defined as cooperating with natural design and humour as individual will and to achieve her goals, submission should be an intrinsic motivation to please. The suggestion is that Martha has no desire or pleasure that originates from her. Ellen Pollak suggests this is either female masochism or validating female virtue as submission to male law.

Martha not only unties courage and softness but also modesty and pride. Softness is a relative term compared to the other women who are portrayed as being aggressive. Modesty in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries referred to self-control and not the unassuming, smallness we associate it with today. Although Martha is praised for her beauty, little attention is given to her physical appearance. Pope mentions her blue eyes, but everything else refers to morals and manners. Martha’s features are clear and unclouded, although he describes her as being marred by smallpox. Despite this, she not only learns to bear them but rises above them, which demonstrates a considerable strength of character. It is also a contrast to the vanity of the other women, a trait condemned in the eighteenth century, despite the objectification of women whose only purpose is to secure a husband.

Martha’s capacity to love also sets her apart from other characters. Milton defines love as refining the thoughts and enlarging the heart. She is therefore directly compared with Cloe, who can think but cannot feel, and Atossa, who can feel but cannot think. Martha possesses both sense (male reason) and sensibility (feminine feeling). The women addressed at the end of the poem are the married woman whose parents could afford a husband, who is portrayed as a tyrant, and the spinster, whom Providence has compensated with sense and good humour. The Pope sees women oppressed by men but suggests she can make the best of a bad situation if she is the master of her passions. He also sees that the only way a woman can preserve her independence is by disguising her feelings.

Pope not only lists the faults of the women in the portraits; he also uses celestial imagery to reinforce his argument. The exceptional lady glows with the moon's sombre (reflected) light compared to the sun's stronger beam. Milton and Pliny before him treat the sun as masculine, burning and absorbing everything, in contrast to the moon as feminine and a delicate planet. When women usurp the male light, they become vain and presumptuous, exposing themselves to public scrutiny and, as a result, suffering the consequences, although he does suggest even men should be wary of the public gaze. The poem reflects the dualities inherent in it: reason and passion, public and private; the symbolism of the sun and moon; art and life, and male and female.