On May 12, 1949, the first successful expedition to photograph Angel Falls from its base and measure its height reached the foot of the enormous waterfall, the tallest on the planet.

In 1946, executives of the Venezuelan airline Aeropostal, visiting New York to recruit pilots for their international office, offered a job to American photojournalist Ruth Robertson (1905-1998)1, then employed by the Herald Tribune of New York, to join the company's Public Relations office in Caracas. Not knowing a word of Spanish, she had heard a rumor from an aviator friend that there was a waterfall “a mile high;” she accepted the Caracas job without a second thought. From then on, she set out to photograph the waterfall from its base. Interviewed in the 1990s, Robertson commented: “Someday someone was going to measure it, and I decided that someone could very well be me.”

Fired weeks after arriving in Caracas (due to political problems with the executive who hired her), she decided to stay in Venezuela, accepting freelance jobs for several American and Venezuelan magazines and companies. She met and befriended Jimmie Angel (1899-1956) whose name was officially assigned to the enormous waterfall (Angel Falls)2 in 1939.

Already planning her expedition to Angel Falls, a friend introduced her to Aleksandrs “Alejandro” Laime (1911-1994)3, a Latvian who had studied engineering and had been living in the surroundings of Auyántepui for years. He had been there at least once and standing alone in front of the waterfall, he came up with the idea of building a tourist site for visitors. Undoubtedly, he was the right man to lead the expedition. Robertson then traveled to the United States and met with the directors of National Geographic magazine, who refused to support her financially, but assured her that, if her expedition was successful, they would like to have the first option to buy her article and photographs. However, she would be required to include in her expedition at least two engineers, so that the measurement of the cataract would be accepted officially worldwide. She already had Laime; she needed another engineer.

Back in Venezuela, searching for financiers, she met an employee of the American embassy, who promised to finance the expedition and to find her an engineer to measure the waterfall. His condition was to move the departure and execution of the expedition by a few weeks. This premature departure would take place in the middle of the dry season, not the best time to measure the waterfall. Robertson thought, “It was the middle of April, the rains had not yet started; the water of the waterfall would be scarce, the rivers low.” Despite accepting the financier's request, once in Uruyén, after only a few days, both her financier and the engineer returned to Caracas.

Robertson talked to her friend the engineer and aviator, Francis Ivan “Shorty” Martin (1896-1952), also a friend of Jimmie and Capitán Alejo Calcaño (Capitán = Captain; it is the term used for the head of any community of Venezuelan Indians, including the Pemón) of San Rafael de Acanaán, Calcaño’s cooperation was vital for having Pemón accompany Robertson’s expedition to Angel Falls. Jorge Marcano, Venezuela's Minister of Communications (who supported the expedition and provided the support of one of his employees, Enrique Gomez, to handle the radio communications) was also contacted. Martin was originally willing to measure the waterfall but was suffering from lumbago. In that state, he drove about five hours to Ciudad Bolívar to meet the plane that would take him to Uruyén. He decided not to go on the expedition, but to support it. He had called colleagues working for the Socony Oil Company to replace him. Perry Lowrey (1916-1977) was chosen to accompany Martin to Uruyén to meet Robertson and her expedition members.

Perry Lowrey was an American engineer working in Venezuela as a surveyor with a group of mostly civil engineers in eastern Venezuela for Socony Oil. He worked there for thirty-three years in numerous positions, each time with increasing responsibilities. He remained in Venezuela until his retirement in 1971 as director of a department at Mobil Oil (the name Socony had changed in the mid-1950s). Just before his retirement, Venezuelan president Rafael Caldera (1916-2009), awarded him the Order of Merit for Work, First Class, for his services to the Venezuelan community.

On the night of April 27, 1949, the engineers working with Martin were waiting at their office to hear from him. They knew of his condition and that one of his colleagues must replace him. They began to prepare the theodolite, an optical instrument for measuring angles. The next day, after Lowrey was chosen, he and Martin arrived in Ciudad Bolivar. And to Uruyén on the night of the 29th. The expedition was momentarily paralyzed, waiting. Their spirits recovered with the engineers' arrival in Uruyén, a village in the valley of Kamarata.

This was not the only mishap in which the expedition found itself. Before Robertson and the expedition members arrived, Laime and a group of Pemón had left looking for a site near the Churún River in the northern area of Auyántepui where he intended to build an airstrip. Then, the expedition members would go by river to the waterfall in canoes, and then on foot. After 10 days of waiting in Uruyén, there was no news from Laime.

Robertson was still counting on Martin. In conversation with him and Lowrey, Martin remarked that "he was too old for the task" and reminded her that, if it seemed convenient, Lowrey would sacrifice his vacation to join the expedition and measure the waterfall. This, if it was still in the plans to continue with the expedition in the absence of Laime and the Pemón accompanying him. Of course, Robertson would continue, and the engineer was needed.

After the meeting, Martin and Lowrey went out to look for Laime and his group, they flew over Salto Hacha, the Canaima Lagoon, and its surroundings. They saw no signs of Laime and the Pemón, so they headed to San Pedro de las Bocas to load the plane with gasoline. Martin decided to stay in San Pedro. Lowrey returned to Uruyén with Oley Olsen. Olsen, a pilot familiar with the area, was supporting the expedition. He had arrived with Robertson and the first group,

Since Laime had not shown up yet, Lowrey intended to pick up the topographic equipment and return to Ciudad Bolivar. But, at the last minute, Laime unexpectedly returned on the night of April 30. Because Robertson insisted, Lowrey decided to stay with the expedition with the firm intention of measuring Angel Falls.

The Pemón who had been with Laime refused to return. In addition, they did not want to enter the canyon of the Churún River (eventually called Devil's Canyon). Laime, Lowrey, and Robertson went to San Rafael de Acanaán to talk with the Capitan for that area of Kamarata, who, upon hearing their reasons, decided to convince another group of Pemón to accompany and support the expedition to the waterfall.

With the support promised by Captain Calcaño, the expedition went to celebrate with Kachiri (Kachiri or Cachiri is an alcoholic drink prepared from the fermentation of cassava or manioc, by Indigenous people of the Venezuelan Guayana, and other native groups in Brazil, Guiana, and Surinam) in the house of Simon Bolívar, Pemón leader of Uruyén, that had taken the name of the Venezuelan Liberator.

In Uruyén, the expedition members waited for a decision regarding which group of Pemón would accompany them and for them to be in the right mood for departure. They had to wait until the "Mawariton" spirits calmed down.

On May 4, after several days of celebration and invocation of good spirits by the Pemón, the expedition members and porters were finally ready to depart from the port of San Rafael. A new route decided with Calcaño included using curiaras (dugout canoes) because the rivers would be the most expeditious route. According to Laime’s calculations, they would leave by the Acanaán, connect with the Carrao, and enter the Churún which at some point would allow them to reach Angel Falls on foot.

They finished bringing their gear from Uruyén, and early in the morning of the 5th, they were en route. On the 7th they were on the Carrao River and spotted Auyántepui in the distance.

Before entering the Churún River in the northern canyon of Auyántepui on the morning of the 9th, the Pemón accompanying the expedition painted their bodies and faces to "protect" and "hide" themselves from the Mawariton spirits that inhabited the tepui. Robertson and Laime painted their faces as a sign of respect. The other expedition members, Lowrey, Ernest Knee (1907-1982), and Gómez, were somewhat skeptical.

During the late afternoon of May 10, with their goal still several kilometers away, they had already spotted the waterfall from the river and they set up camp. They would start the hike to the foot of the waterfall the next day.

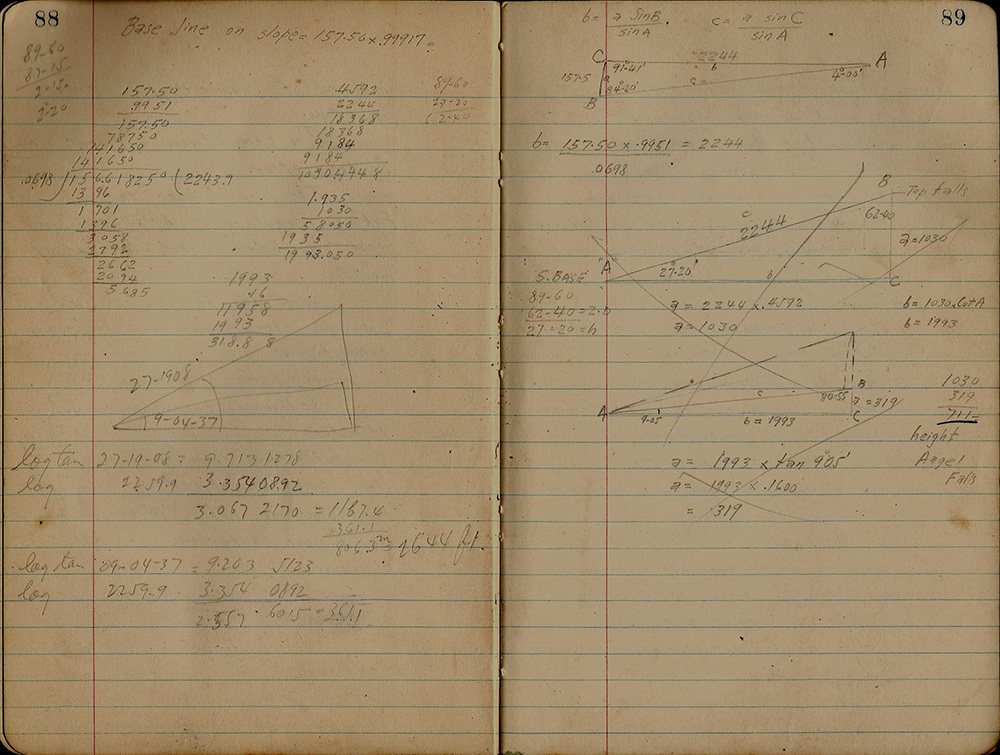

The last phase of the hike began on May 11. Lowrey and Laime planned to clear a path to the falls to estimate its size. They were then a couple of kilometers away from the falls. Lowrey observed, "The waterfall starts as two streams. These merge about a quarter of the way down and turn to spray well before hitting the bottom." There was a full moon, and the night was clear enough that the waterfall could be seen in the distance. Lowrey also measured the longitude and latitude of several stars. May 12. The expedition members informed Caracas and the world that they had reached their destination. During the afternoon, Laime and his "muchachos" had cleared a line of vision to the base of the falls that Lowrey could use for his measurements. Lowrey and Laime triangulated the huge waterfall using the measurement lines made earlier.

May 13. After spending a couple of hours among the rocky stretches that Laime and his team had prepared, Lowrey announced to the group his first measurement of the waterfall's free fall. He estimated about 700 meters (~2200 feet), not the "mile" Jimmie Angel had estimated a few years earlier.

Flying solo on November 16, 1933, Angel found a huge and unknown waterfall falling from Auyántepui. Using his plane's instruments, he measured it on November 22—the third time he flew in front of it and calculated that it was one mile high. His flight log reads "Flight over the huge waterfall - 1 - mile". He let friends and acquaintances, including Robertson, know this after meeting her in Caracas. Lowrey and the group were saddened because the news was taken as a "half-failure," ... was it because it was Friday the 13th? Exhaustion is general.

Perry Lowrey's Angel Falls height calculations

Perry Lowrey's Angel Falls height calculations

May 14. Dawn. Everyone had slept well; the pressure was down. Robertson took photos of each person, the group, and the waterfall. Lowrey repeated his measurements, "I'm refiguring everything and now I get 711 meters." He was referring to the free fall of the waterfall, which on further corroboration resulted in a slightly higher number and the final measurement. This was corroborated by Robertson who wrote,

Perry, after hours of figuring angles, zenith distances, talus slopes, and what not, came up with 2,648 feet [807 meters] for the main drop of Angel Falls. Counting in the lower falls, the vertical drop is a total of 3,212 feet [979 meters]. No doubt now [Angel Falls is] … the world’s highest.

Notes

1 For more information about Ruth Robertson.

2 Access to the article On the trail of Angel Falls.

3 More on Aleksandrs “Alejandro” Laime.

Aguerrevere, S., López, V.M., Delgado O., C. and Freeman, C. (1939). Exploración de la Gran Sabana. Revista de Fomento, 3(19): 501-735.

González, J. M. (2019). Ruth Robertson: Grande Dame of Angel Falls. In: Angel, K. 2019. Angel’s Flight. The life of Jimmie Angel, American Aviator-Explorer, Discoverer of Angel Falls. Eureka, California: Jimmie Angel Historical Project. pp. 350-357, 410-414.

González, J. M. (2023). Tras la pista del Salto Angel. Ni la cascada Pacaraima, ni el Gran Salto del Caroní, (pp. 306-316). In: Aveledo, J. Operación Auyantepui 1970. El rescate del avión de Jimmie Angel. Miami: Independent Publication.

González, J. M. and P. Pérez. (2008, January 28). La expedicionaria olvidada. Se cumplen 10 años de la desaparición de la mujer que logró medir la altura del Churún Merú. El Nacional. Ciencia y Ambiente, pp. 8.

Robertson, R. (1949). Jungle Journey to the World’s Highest Waterfall. National Geographic Magazine, 96(5): 655-690.

Robertson, R. (1975). Churún Meru. The tallest Angel of jungles and other journeys. Ardmore, Pennsylvania: Whitmore Publishing Company. 345 pp.

Robertson, R. (1990). A photographic gift of a Venezuelan trek. National Geographic Magazine. 178(3): vi.

Simpson, G.G. (1940) Los indios Kamarakotos: tribu Caribe de la Guayana Venezolana. Revista de Fomento, 3(22-25): 201-660.

Socorro, A. (1948). Octava maravilla del mundo. El Salto Ángel. El Gráfico. Diciembre, 7.