It was during the COVID 10 pandemic in 2020 that I decided to double down on completing what became my first novel, Year of the Earth Serpent Changing Colors (Ibidem-Verlag/Columbia University Press, 2023), that I had been working on for 30 years since 1989, after having taught at the Johns Hopkins-Nanjing Centre in Nanjing, China, during the tumultuous year of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1988–89.

The second novel, Year of the Horseshoe Bat—in Exile (Ibidem-Verlag/Columbia University Press, 2024), was then inspired by events that took place years after the June 1989 Beijing repression, and based in part on my experiences living in Paris during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–22.

I found the sudden rise of the Chinese democracy movement from April 1989 to the June 4th 1989 Beijing Repression so profound that I realized that the experience could not be expressed by traditional political science discourse. I had given an introductory lecture at Beijing University in November 1988 on the subject of American democracy and tried to explain how the US electoral college system worked and how it would put George Bush, Sr., in power regardless of the popular vote. My lecture was insignificant in itself; yet I later realized its significance arose from the fact that it was organized by the students themselves and not the university authorities.

In effect, as time passed, I realized the June 1989 nation-wide repression represented the opening post-Cold War salvo in what has become an Eurasian backlash led by China and Russia against the US and its liberal democratic allies and US efforts to support democracy movements abroad. And now other forms of neo-authoritarian backlash are impacting both Europe and even the US itself, at least since Donald Trump (whose media image of Donald “Agent Orange Jee-Zus!!!” Drumpf plays a role in the novel) was elected US president in 2016.

So in addition to writing a number of more traditional political science books that have dealt with the impact of the collapse of the Soviet Union upon China, such as Surviving the Millennium (1994), Dangerous Crossroads (1997), Averting Global War (2008), World War Trump (2018), and more recently Toward an Alternative Transatlantic Strategy (2020), I opted to write two novels about my experiences in China. And I intend to write a third novel to form a trilogy in a year or so.

My goal in writing these novels is to show how individuals can be caught up in the dynamics of history and the global geopolitical struggles of their respective eras, whether they intentionally want to be a part of those struggles or not. The purpose of my writing is to reveal how the social, cultural, and political interactions between China, Europe, and the U.S. impact both societies and individuals from behind the scenes, at least since the days of Marco Polo. The all-seeing chimera of Marco Polo accordingly plays a major role in the third concluding section of the first novel, Year of the Earth Serpent Changing Colors.

One can read the second novel, Year of the Horseshoe Bat―In Exile, without reading the first, but the personal backgrounds of some of the characters, and particularly themes dealing with historical figures in Chinese history, syncretic religions and revolution, and forces beyond human control―may not be fully understood…

Year of the Earth Serpent Changing Colors

Set in Beijing, the first novel, Year of the Earth Serpent Changing Colors, explores the social, cultural, and geopolitical transformations and hopes for democratic reform in China and the world at the end of the Cold War. These hopes for democratic change are seen through the cynical eyes of a self-proclaimed American Maoist, Mylex H. Galvin, the protagonist, who slowly begins to realize that only fanatics in China still believe in Maoism. Mao is dead! Long live Mao!!

Hired to teach English as a foreign language, Galvin records his experience in his “Anti-Marco Polo” journal after he meets ex-pats from around the world, while trying to come to grips with the Chinese language, history, society, and politics. Over time, Galvin becomes disillusioned with the poverty and environmental destruction that he finds in China; his barefoot doctor heroes are not capable of treating AIDS; and Chinese and African students clash in Nanjing in December 1988—with no sense of international solidarity.

As the democracy movement heats up, he is torn between the love of Tao Baiqing, a Daoist, and Mo Li, a student of English Lit, and he unwittingly betrays to her the ties between the journalist, Hayford, and the democracy activist Chia Pao-yu, who opposes the corrupt Communist regime. Chia is then accused by Beijing of leaking “top secrets” to the journalist Hayford as the democracy movement heats up.

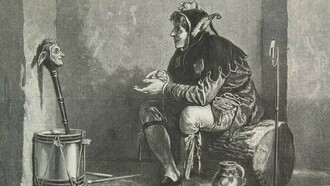

As the novel ends, Mylex H. Galvin enters into a deep depression once he returns to Washington, DC. It is a deep depression that is in part caused by the realization that he had dedicated his life to a failed and repressive totalitarian ideology. At the same time, he does not believe in the “End of History”―an essentially American ideology that began to gain a global following in 1989. He is not convinced that American-style liberal democracy will transform the world. In his cynical perspective, American democracy is a farce, a ridiculous battle between the wealthy lawyers of Democratic “Tweedledees” and the even richer businessmen of Republican “Tweedledums” who do nothing for the people. Galvin, for example, had written Mao’s name on his ballot instead of voting for Bush or Dukakis in the 1988 presidential elections.

Galvin’s depression also stems from the fact that it might have been his own stupidity that let his so-called "girlfriend,” Mo Li, find out about the relationship between the American journalist, Mark King Hayford and Chia Pao-yu, and who then told the authorities.

At the end of the first novel, it is believed the Chia has been imprisoned or even executed by Chinese authorities for helping to organize the Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing in April-June 1989 and for allegedly leaking “top secrets” to the American journalist.

Galvin’s deep depression ends in his death in an apparent suicide, although it is not at all clear that he actually killed himself. Perhaps he was killed by a character who appeared to look just like Marco Polo in Galvin’s drug-induced hallucinations?

Year of the horseshoe bat—in exile

In the sequel, Year of the Horseshoe Bat—in Exile, we find out that Chia Pao-yu was not executed as had been believed and was lucky to escape to France, with the help of the French and American secret services, Chinese Triads (mafias), Buddhists, and pro-democracy organizers. He is now living in exile in Paris under an assumed name, Jean Valjaur (JV).

In Paris, after waiting tables in a French restaurant, Chia finally finds work with the Foundation for Human Values Forever (HVF), directed by the charismatic feminist Bereft LaPlante. He meets dissidents like himself from the ex-Soviet Union, the Middle East, and many other countries. Many have been persecuted for their political views and gender.

Chia goes out with the staff of the HVF Foundation to the French National Stadium to watch the French-German soccer game on the very night of the Bataclan terrorist attacks on Friday, November 13, 2015. He also witnesses the Yellow Vest protests, and survives the COVID-19 (or Horseshoe Bat) pandemic after having survived the AIDS pandemic in China in the 1980s.

In pursuing his self-study of American culture, in the hope that he will eventually complete a PhD, he critiques the social and political views of the Beat poets, like the Jewish Buddhist Allen Ginsberg, and pop artists, like Warhol and Basquiat. The latter’s painting, “China and Paramount,” for example, satirically depicts the influence of China on Hollywood. Chia also comments on the feminist politics of the movie, Barbie. He finds it ridiculous, for example, that Hanoi protested against that movie for showing a children’s map of the South China Sea that appeared to confirm China’s irredentist claims to the region, while other countries denounced its feminist message. Concurrently, Chia scathingly condemns western “Maoists,” like Mylex H. Galvin, the pro- or ant-agonist of the first novel—whom he had met at Beijing University during the 1989 protests—and whom Chia now depicts as a “Wokeist” before his time.

Become a French citizen, Chia participates in the Hong Kong protests against the takeover over by the Chinese Mainland. Later, he takes part in an academic conference on the “Future of China” in Washington, D.C. There, he witnesses President Trump’s threat to call in U.S. “G.I. Joes” to repress demonstrators who were protesting against the killing of George Floyd in June 2020. It is a threat that recalls the June 1989 Tiananmen Square repression by the People’s Liberation Army―as ordered by Chinese leaders, Deng Xiao Ping and Li Peng.

Chia is outraged to hear an American president, Donald “Agent Oange Jee-Zus!!!” Drumpf, boast out loud, dubiously in jest, that he wished he possessed authoritarian presidential powers like those of Xi Jinping. Drumpf’s boast was contrary to everything Chia had struggled against in 1989 and for which he had risked his life. Chia had believed that the Americans were 100% behind the Chinese democracy movement―but now he had begun to see that was not necessarily the case.

Back in Paris, Chia accidentally learns at a fundraiser that the HVF Foundation finances rather questionable activities not related to humanitarian causes—and quits his job after a drunken LaPlante, accused of anti-Semitism, attempts to seduce him. Chia finds out that LaPlante is making herself rich through her human rights and refugee charity work—in that she can legally take very high percentages of the funds raised as personal income, among other legal tax tricks to boost her income.

After quitting the HVF Foundation, he then starts to work for the secretive Society for the Exploration of Cosmic Consciousness (SECC), which publishes a version of his “Planetary Manifesto” that is redacted by artificial intelligence. In the redacted version, his warning of war between China and Taiwan now appears lost in the babble of social media and the Internet. If the U.S. Balding Eagle, the Chinese Red Dragon, and the Russian Double-Headed Eagle cannot soon resolve their differences, then the popular hopes of “Barbies” and “Kens” for global peace will soon be crushed by the boots of “G.I. Joe” and rival militias.

Chia unepxectedly disappears in a suspected trade-off for a Western spy held by Beijing—at least that is how the Global News Media carries the story.

Authoritarianism, new slavery, prophecy

The novel deals with a number of themes, including the nature of democracy in an era of rising authoritarianism, the new forms of slavery, and prophecy.

Both novels deal with the question of democracy with respect to the idealistic hopes of Chinese students in their peaceful struggle against the corrupt Communist Party monolith. Although he is not as cynical as Galvin, Chia begins to question whether the US system of government is truly democratic, given its tendencies to serve plutocratic interests despite (or because of) its excessive system of checks and balances. He also questions whether the Yellow Vest protests in France will lead to a more inclusive democracy, or else a more hardline authoritarianism of the Far Left or of the Far Right. He thus begins to advocate for more truly democratic forms of state governance, including greater degrees of workplace democracy and employee stock ownership.

In terms of the themes of slavery, one feminist activist invited by Berefte LaPlante to take part in her HVF Foundation speakers series denounces a new form of “Brave New World baby-making” slavery in which poor and migrant women are being forced by mafias to become surrogate mothers. Yet because LaPlante’s speaker, Leila Zarwish, is of Palestinian origins, it leads some of her public and potential donors to believe LaPlante is “antisemitic.”

This allegation is made along with the fact that LaPlante supposedly made “antisemitic” remarks in French on TV and that some of the HVF Foundation funding for the protection of refugees comes from wealthy Arab sources. As is the case for all forms of racism, “antisemitism” is a real danger and can lead to discrimination and political persecution of Jewish populations, if not much worse. At the same time, false charges of “antisemitism” can be used to vilify and denounce individuals and can become a propaganda tool used against those who may oppose, even for legitimate ethical and political reasons, Israel’s social and political policies.

In terms of themes of prophecy, Chia had warned at the time of the democracy protests that if the Chinese democracy movement does not prove successful, then the Chinese New Authoritarians will take power. Although some scholars made the argument that China would soon democratize, even after the nationwide repression, as younger generations entered into power, Chia’s prophecy in the first novel is confirmed in the second book after Xi Jinping comes to power and is voted “president for life” in 2018.

Yet once again, what really enrages Chia is to hear the US president, Donald Drumpf, state publicly that he wishes he possessed powers like those of Xi Jinping—thereby raising the prospects that an authoritarian movement could take over even in the Land of the Free, much as Sinclair Lewis had forewarned in his satirical novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935).

Chia’s second prophecy is that new forms of authoritarianism could soon take hold in the US, France, and Europe. Reacting to his American Maoist nemesis, Mylex H. Galvin, and to the politically-engaged Jewish Buddhist, Allen Ginsberg, Chia warns that America’s decline, as foreseen by Ginsberg’s books, Fall of America and Howl, and poems like "America," among others, must not be followed by China’s ascendency to global hegemony…

And the third prophecy: If there is no compromise between Beijing and Washington, the world will slide backwards into the “Armageddon to end all Armageddons." Russia-Ukraine wars over the Black Sea, and the Israel-Hamas-Iran wars over ancient Megiddo have already begun. One of the next wars could be China-Taiwan-US...

Those are just some of the themes of the second novel that represents a plea for amnesty for those who were imprisoned or exiled as a result of their nonviolent activism in China and elsewhere.

And let us hope Chia’s latter prophecies prove wrong!!!