There is a country in the world situated right in the sun’s path.

(Pedro Mir)

On the 19th of May, the Dominican Republic held presidential elections. The results were of no surprise to the Dominican electorate. Incumbent President Luis Abinader secured his reelection for the next four years.

Despite the extraordinary margin of victory, it made absolutely no headlines. Not a single eye was batted and nor was a single eyebrow waisted. The results were expected, and it is precisely this lack of surprise that has a lot to say about how different politics in the 11 million people country are compared to the rest of the region.

Breaking with tradition

Latin America has a history of convulsed, often bloody elections. Strongmen, fraud, and coups are the bread and butter of election cycles. Between 2019 and 2023, Venezuela had two presidents and each was recognised by different countries and organisations. In 2006, now president of Mexico Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, refused to accept election results and even held his own swearing-in ceremony. In Perú, the office of the presidency has become more of an internship than a full-time, four-year job.

The Dominican Republic has distinguished itself for its solid democratic institutions since the second half of the 20th century. While the cold war raged on and dictatorships were spawning left and right on both the left and the right, Dominican presidents calmly handed over power to their successors.

This strong pro-democracy momentum did not come out of nowhere. Between 1930 and 1961 the country was ruled with an iron fist by Generalissimo Rafael Trujillo. After his assassination, the country lived a period of crisis marked by military flirtations, weak governments, the exile of poet-professor-president Juan Bosch in 1963, and a civil war in 1965.

The first electuons held in DR after the fall of Trujillo that produced a stable government where in 1966 where the former Trujillo ally Joaquin Balaguer was inmaugurated president. It would be his first of three presidencies in a row and, amazingly, he would come back twenty years later to win three more while completely blind.

The first 12 years of the veteran strongman Balaguer were marked by the impetus to keep the army and communist insurgencies controlled. His practices included repression of civil rights, appointing allies in the armed forces, and election fraud. At the end of his third government, however, he conceded defeat and handed over the reins to center-left candidate Antonio Guzmán Fernández.This smooth transition of power effectively marked the end of post-trujillismo and the start of the solid democracy we see today.

Neither this nor that, but the exact opposite

Since the fall of Trujillo and the non-kosher methods of Balaguer, alternation has become the norm in Dominican politics. From 1978 to 1986, the center-left PRD party governed before Balaguer came back three more times. After his highly questioned victory in the 1994 elections, the public backlash led Balaguer to promise to leave power after two years instead of four and call for elections. Balaguer joined forces with his longtime rival and left-wing nationalist Juan Bosch on a centrist platform to push forward the charismatic wonder boy Leonel Fernández to the presidency and prevent the social democrat José Francisco Peña Gómez from winning. The gambit paid off, and in 2000, Leonel handed over power to Hipólito Mejia, himself running on a social democratic platform.

It seems like the Dominican Republic had no room for hegemonies and was a healthy democracy where two major forces hovered around power and gallantly let the other side take its turn. After the end of the Mejía administration, Leonel came back and rewrote the constitution to allow for a third term. This set the dangerous precedent of bending institutions to serve those in power.

It must be noted that this took place in the first decade of the 2000s, when the “pink tide” engulfed Latin America, and Chávez, Kirchner, and Lula were all up to the same electoral shenanigans. After Leonel’s third presidency, he passed power onto his ally Danilo Medina who comfortably won two elections in a row.

This brings us to 2020 when Medina, Leonel & Co. were not able to secure another victory, and outsider-businessman Luis Abinader won comfortably with a difference of over 600 thousand votes. It must be noted that this election took place duing the pandemic, and it was a time when outsiders dominated elections all over the world. The general trend is that people simply voted against whomever was in power. Keeping with tradition of the past 20 years, “Uncle Abi” as he is known, just booked another four-year stay at the presidential palace.

Political indifference and irrelevance as part of Dominican life

But do people care? Do Dominicans care about leaders knowing an election victory is essentially a guarantee of two terms? No. Apparently no one does.

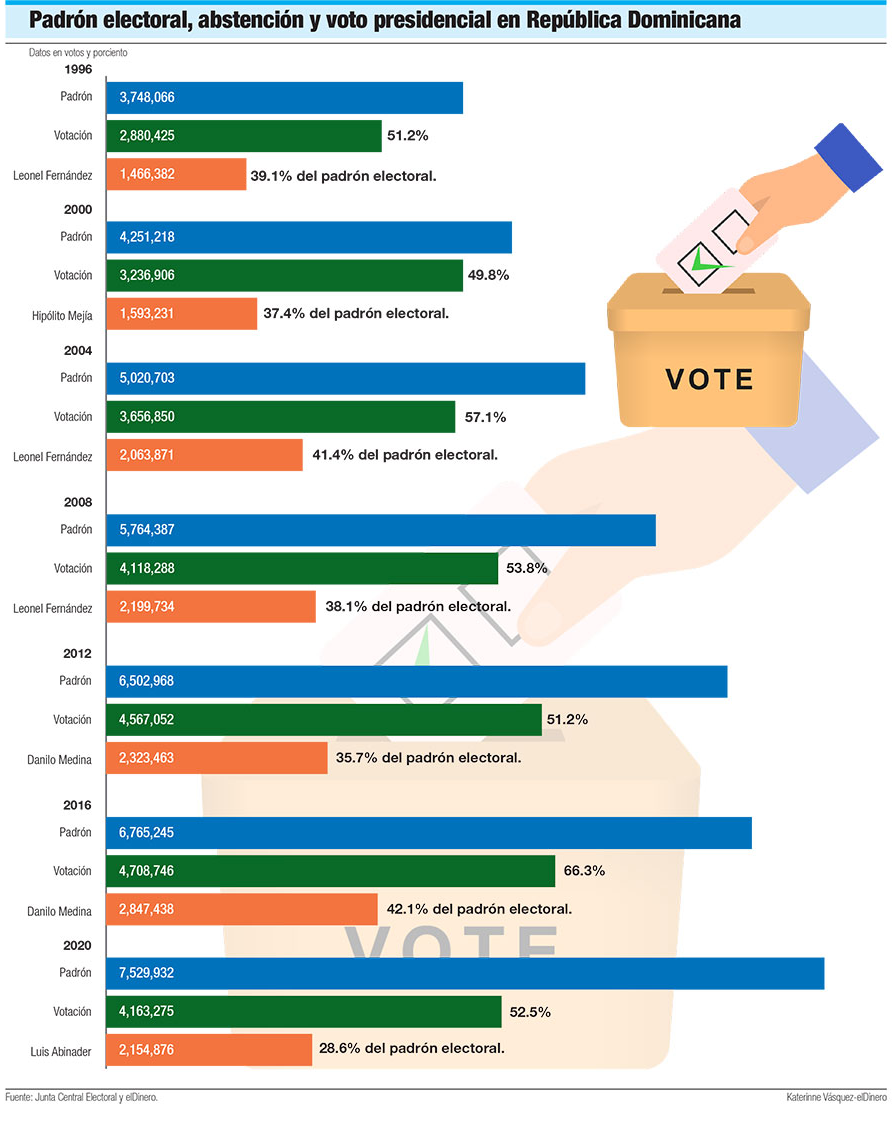

The following chart shows the election results of the elections discussed above. The winner is in orange, total votes in green, and registered voters in blue.

From El Dinero.

As we can see, all presidents won with a comfortable distance of their rivals. There were no razor thin margins, no recount scandals, and no supreme court decisions. The bulk of Dominican voters tend to agree on a candidate and the extreme polarization of Latin American politics is not found in the Dominican Republic.

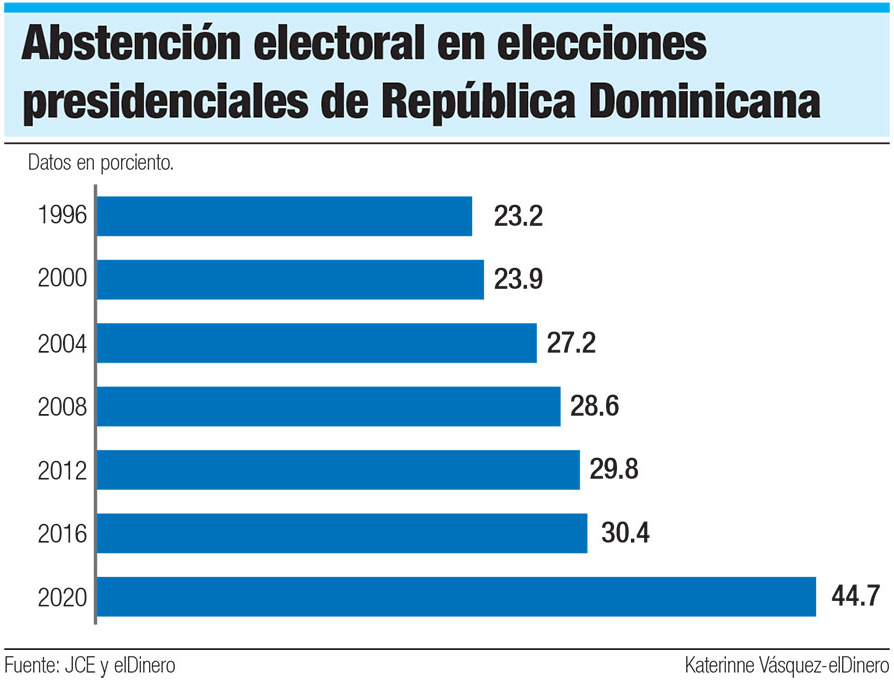

Another factor worth considering is the high rate of absenteeism. A sizeable portion of Dominicans don’t care about who is in power. The following chart displays absentee rates.

From El Dinero.

It seems that Dominican voters tned to agree on a candidate and, sometimes, they dont care.

An explanation

How can the indifference Dominicans feel toward their presidents be explained? Why do they overwhelmingly support a dude and just let him stay there an extra four years? And why do some not care at all?

My guess is that the Dominican Republic is comparatively easy to govern. Population is small, homogenous and GDP has consistently increased every year for the past thirty years. All governments, all things considered, have done a good job. Unless there is a major issue like a pandemic, all governments essentially have to do the same and citizens will vote for the same.

As the larger portion of the island of Hispaniola, the other side being the ever-troubled Haiti, the Dominican Republic operates as an island economy. This means that a checklist of needs must be attended to regardless of ideology. Most goods are imported so tariffs are kept low and exchange rates stable. Free trade zones and other incentives prop up jobs and increase output. Also being small in terms of population and size, it is easy to connect the country with a few major infrastructure projects. In addition, the tourism sector is efficiently ran by private companies. The results speak for themselves, approximately 10 million tourists visit every year which is almost the entire population of the country. Here, its strategic position in the middle of the Caribbean plays a role since the country is reachable without layovers to all major cities in the Americas and Europe. In other words, as an island country, government officials know that sound finances and common sense are enough to steer the ship of State.

A major mismanagement could represent a catastrophe. Inflation could decimate the mostly-middle income country. Shortages of food in an island represent larger problems than in continental countries. Lack of employment opportunities generates mass-migration and low birth rates which in turn creates an aging-population. To prevent this, Dominican officials are committed to continue working hand-in-hand with the private sector. Incentives are offered to manufacturers, strong supply lines with shipping companies and logistics operators are guaranteed, and tourism runs on its own.

To conclude, we can say that the solid democratic institutions in the Dominican Republic are due to the country practically being on autopilot. The unique conditions of the country make all ideological nuts unfit to govern. A hard veer left is as improbable as a hard veer right. While this does not mean that an AI model could run the country, perhaps a team of McKinsey consultants could.

As of 2024, the sun continues to shine bright for the country right in its path, and I wish the best to Luis Abinader and to whomever comes after, not like the name matters.