Why have we seen unfavorable trends in the ranking of European countries in the world rankings for country innovation in recent decades? What are the scale and wider significance of this problem, and what should be done to reverse this trend and turn it in a positive direction? According to the European Innovation Index, we have advanced annually by 9.9% in the 2015–2022 period, and some countries even four times less. Our additional challenge is that, as a society, we are not sufficiently aware of this problem, and consequently, we are not motivated to tackle it more decisively and in a more organized manner.

The problems in this area will be illustrated by the case of Slovenia, which has been stagnating and, for some years, even deteriorating in the field of financing research and innovation activities for the last 15-20 years.

One of the key reasons for Slovenian lag is insufficient public funding. While this share in total funding for innovation activity (GERD) in 2009 was 35% of the EU average, the Slovenian share fell to only 29% by 2016.

When we compare the GDP of Slovenia with the average in the EU or OECD countries, we see that Slovenia is lagging behind, which cannot leave us indifferent. The comparison of total GERD assets in Slovenia and Austria per million inhabitants is as high as 1 versus 2.6.

It is important to find the right answers to these questions as soon as possible, as it has been proven that innovation is crucial for the competitiveness and thus competitiveness of countries where problems are consequently also detected: in 2022, Slovenia is lagging behind the EU average by 14 points in the labor productivity index. In the innovation distribution of EU Member States, a few years ago, Slovenia fell from the second to the third group of 'Modest Innovators'. If this negative trend is not fully acknowledged, it will be difficult to avoid the fate of colonial economies, where people have to work year after year more to maintain their modest standard of living, and their governments are unable to kick-start dynamic and sustainable economic development as well as effectively address serious brain drain.

As we see, there is no consistent progress. Meanwhile, when comparing Slovenia with Austria, the latter’s GDP has consistently been rising over the past decade, from 1.9% to 3.2%, with more dynamic GDP growth than Slovenia’s. The difference stems primarily from the Austrian government's commitment to strengthen the country’s international competitiveness based on knowledge and innovation, which they have succeeded in, as they rank 9th among the most competitive countries in the world (their working hours are worth $79.4 while Slovenian ones are only $20).

Slovenia's position is highly indicative and reflects unfavorable tendencies in the development of the innovation capacity of several European countries and the continent as a whole.

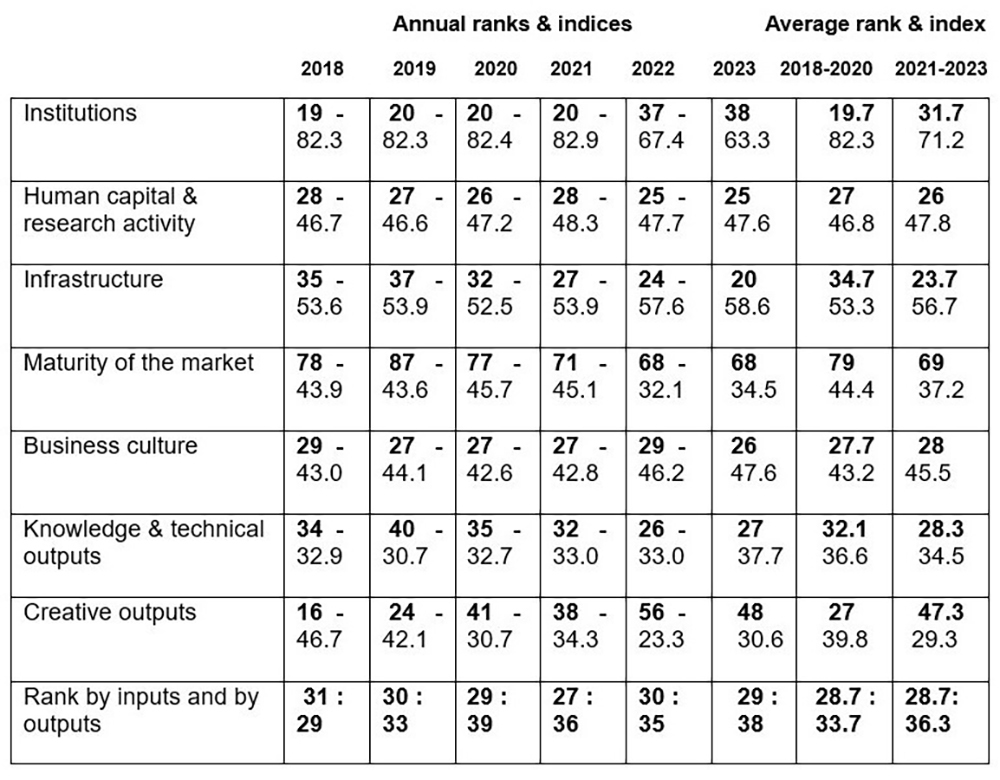

Let's see Slovenia's rankings at the annual innovation rankings of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) for the period 2018–2023 by 7 key areas and the ratio of ranks for innovation inputs and outputs. The latter makes it very clear that, as a result, Slovenia is not efficient enough to achieve satisfactory progress.

Slovenia by Global Innovation Index, 2018–2023 (Rang and Index):

Source: Annual reports of the Global Innovation Index for the period 2018-2023, WIPO, Geneva.

Overall, these rankings show a favorable position for Slovenia only in the fields of human capital, knowledge, and technical products, as well as infrastructure and business culture, but an unsatisfactory position in the quality of institutions, market development, and creative outputs.

What does the data in the table above show us in more detail?

- In terms of the quality of institutions, the company recorded a negative trend in ranking from 19th to 38th place (significant deterioration over the last two years).

- In terms of human capital and research, Slovenia is making some progress (from 28th to 25th). Even more pronounced is the progress in infrastructure (from 35th to 20th).

- In terms of market development, Slovenia is by far the worst ranked among the 7 areas, although with some improvement in the last two years (from 79th to 69th).

- In terms of business culture, Slovenia is quite stable and favorably ranked (27th to 29th), and it is similar, but with visible progress, in the field of knowledge and technical outputs (up from 34th to 26th).

- After creative outputs, Slovenia recorded a painful deterioration (from the 16th to the 56th place last year, but with some improvement this year with the 48th position).

Point 3 (market development) consists of three groups of indicators: loans, investments and diversification, and market size. In the first group (78), the worst rank went to domestic lending to the private sector; in the second group, risk capital (rank 82); and in the third group, domestic market (rank 90). There is, of course, nothing to do here, Slovenia being a small country of 2 million people.

Point 5 (creative outputs) covers the following groups of indicators: intangible assets, creative goods and services, and online creativity. In the first group, Slovenia ranks the lowest in terms of percentage share among the top five sources (rank 77), in the share of global brands (first 5,000) as share of GDP (rank 62), and in original industrial design (rank 38).

At the same time, one cannot ignore the conclusion that Slovenia, as in many European countries, has obviously not done enough to create the conditions in which innovation activities take place, referred to in the professional literature as the "innovation ecosystem." This is significantly more important today than in the times of the “linear innovation system." When we define the concept of an innovation ecosystem, it is easier to understand why Europe is not successful enough. It is a set of policies, actors, and activities that create the conditions for successful innovation activity. Not only the governments, but actually the whole society, is not sufficiently aware of the importance of innovation activity.

Most European countries maintain institutions, bodies, and services that are not sufficiently adapted to the needs of modern innovation activity. This is very clearly and convincingly reflected in the poor rankings in the table above, but they undoubtedly also indicate who bears a large share of the responsibility for the status quo. It is the governments, of course, first and foremost, because they have the power to make the necessary changes, but they underperform. However, the business community, as well as the academic community—being the main drivers of innovation—are also not doing enough to make the necessary systemic changes around Europe.

According to official data, in the last 15 years, Slovenia has invested in innovation activity even above the EU average (in 2012–2013, above 2.5% of GDP), but unfortunately, by 2018, the GERD had again fallen to 1.7%. However, in the last 5 years, it has been growing again, and (including EU resources), Slovenia is now only slightly below the EU average of 2.27% of GDP in 2021. Among innovation-successful countries, none of them spend less than 2.5% on supporting innovation, and some spend even above 3% of GDP. Among the worst 30 innovation countries, no one gives even 1% of GDP. In short, there is no doubt that innovation success cannot be achieved without adequate investment, both from private and public sources.

The Slovenian problem is that the public part accounts for only about a fifth of total funding, while this share in the EU is on average around 45%—that is, double—while the economy contributes 49% and spends 73% of total GERD funds.

Another challenge in government funding is that it is not mainly active funding but a 100% tax exemption on declared research costs of companies (but “only” 60% in Austria). This means, on the one hand, supporting companies in investing in R&D activities while reducing state tax revenues. When the share of tax deductions rose from 60% to 100%, Slovenia—certainly not by chance—recorded a sharp increase in the number of researchers in the economy. This, of course, is not bad in itself, unless it was to a significant extent classifying employees as R&D staff in order to make the most of the tax deductions offered. In this case, it is an abuse of the tax benefit scheme and turned out to be a pure subsidy. This is contrary to European and Slovenian legislation.

While universal tax breaks have fewer things to do, there is no guarantee that they are more effective, as most European countries have opted for different approaches (Sweden and Estonia have the best solutions, according to the OECD). As a result of the Slovenian model, the state has reduced possibilities to influence areas where promising R&D activity is actually developing, which would be important in the function of supporting development priorities, which, unfortunately, Slovenia has not clearly defined despite numerous strategic documents.

In addition to the insufficient amount of public and private funding for innovation activity—where we are not all doing enough together—there is also a problem with the funding system itself. Of course, it is not only a matter of financing research and development but also, if not more, of the ways and forms of financing innovation and entrepreneurship. The biggest Slovenian problem in this area is the serious absence of risk capital; according to the OECD, it was estimated to be only USD 6.3 million in Slovenia in 2020. In terms of GDP, in Slovenia it is 6 times less than in the EU and 15 times less than in the USA. This means a factor of 30, which unfortunately still does not wake up Slovenian authorities, but it does explain the painful differences between Slovenia, Europe, and the US. While in America, promising entrepreneurs with good projects have no problem obtaining needed capital (it is literally thrown at them), in Europe, in addition to the insufficient amount of risk capital available, the entire financing system is much more bureaucratic, and in Slovenia even more than in most European countries.

The system of public funding for innovation activity in Slovenia is still essentially focused mainly on scientific research projects, which are evaluated from the point of view of their scientific excellence and their market potential. So that there is no misunderstanding, without good science, there can be no progress, and it must certainly be adequately funded, because without good science, there is no innovation either. At the same time, without adequate forms of financial support for innovation projects, innovation remains a secondary objective, which means that it remains unconfirmed on the market and ends up as an invention, in the best case interesting only for academia.

Three American authors, J. Mariani, D.L. Wince-Smith, Ch. Evans, and W.D. Eggers, in their article "The Role of Government in Innovation" (Deloitte Insights), define clearly the three key components of innovation process management:

- Identification of actors and joint decision on objectives.

- Understanding the risks and encouragements of actors.

- Creating measures that shape behavior in the market.

The biggest challenge for Europe—besides better and more appropriately funded research and innovation—remains connecting better business and academia in order to support the development of inventions into innovations. And, as already mentioned, the responsibility for this transformation remains not only on the governments but also on academia, business, and the rest of society, including NGOs and the media.