Imagine a world where facts are no longer the foundation of our beliefs, where emotions and personal values hold more sway than objective reality. This might sound like a dystopian future, but in many ways, it describes the present. In 2016, the Oxford Dictionary declared "post-truth" the word of the year, reflecting a growing trend where truth becomes blurred and emotional appeal often overrides factual accuracy. The Brexit campaign and the US presidential election that year exemplified this shift, with misleading claims and fake news stories shaping public opinion more powerfully than verified facts. But is this phenomenon truly new?

Max Weber, in his book Economy and Society (1921), already stated two ideal types of rationality. One is instrumental, which is completely calculable. It is an analytic tool with which we assess situations—probabilities and risks alike—causalities or (co)relations. The other one is axiological rationality. This type of rationality is imbued with emotions and values. For example, one may see certain kinds of action (which are value-oriented) as completely irrational, but the person who does them is led by something meaningful and rationally oriented. To pray to God, for example, is a kind of axiological rationality. It is completely rational to pray to win a lottery; however, from the instrumental side of the argument, it does not make sense. But are we wrong to pray?

By making a fetish of instrumental rationality in the past 200 years, it may seem so—at least from the perspective of science. But the world of everyday life, no matter the rise of instrumental rationality, kept axiological rationality as a backup plan. A plan which became the core of meaning creation in the contemporary world. As certainty became more and more important, values and emotions—something that gives definitive answers—rose up as a mode of orientation. Therefore, post-truth society, if we embrace this phrase, is a normal outcome of the risk society that deals with uncertainty in a new manner that is not understandable by modern conditions. However, what is of importance in this article is the very phenomenology of post-truth.

It is easy to enchant ourselves with the pessimistic, apocalyptic claims that truth no longer matters or even exists—that emotional and personal beliefs hold more sway in influencing societal attitudes and actions than objective facts. It may be so if we agree on what truth essentially is. But throughout the rise of thought and reason, we did not come to a definitive, or at least instrumental, answer to the question of what truth is. The closest we came is the essentialization of truth by science, and it is a wonderful effort if we include everything that humankind (at least technologically) has achieved. Truth in that scientific sense is not something inherently human but systematic. Truth is a result of complex relations between individuals seeking truth in a programmatic manner (in science through methodology and theory). But even this kind of essentialization is constructivist in nature. The truth in science is not something fixed, but built through observation, critical thinking, and guidance.

In a world of authenticity, we have embraced two of these in everyday life. We are more observant of our environment than ever. Nothing is taken for granted anymore. In this non-taken-for-grantedness, we have even become more critical. We try to evaluate and make sense of the observed things. However, this critical thinking is a wild one, as the third part of the puzzle is missing—guidance. As we become more oriented towards ourselves, we make these observations and critiques without the necessary knowledge or the authority that is devoted to seeking the truth.

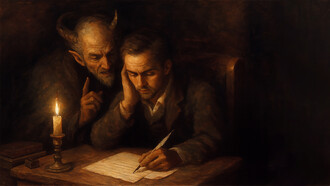

If our truth-seeking is guideless and centered around our own desire to be the holder of the truth, then the quest for truth will be a short one. We will find truth by narcissistically placing ourselves above everyone else. This truth is still a truth, but it is a truth that is a product of the will to dominate. No matter if domination is happening in the peer group, family, or on the larger scale of the state and cosmopolitan world, truth is separated from the facts. It becomes the force that dominates. I need to prove that I am right, not because of the truth, but because I cannot lose this perfect picture of myself.

But now the next question is: why would someone accept this kind of truth from others? Why not stay with the scientific authority of truth and claim populist truths instead, or at least be skeptical of these new forms of truth from above? We embrace this truth not to be dominated, but to feel safer through the dominance of others. The embrace of truth, which is dominance, serves to provoke another dominance where we will be in charge. In our own narcissism, we do not even accept the fact that this kind of truth is domination placed upon us. We see Donald Trump or any other icon of today's "alternate fact" truth (and there are plenty of choices) not as someone who is manipulating us, but as someone who is enabling us to be authentic, smart, adventurous, rebellious, and also safe at the same time. It also arms us against those who think otherwise, challenging our new safety and narcissistic ideal. The ideals of this new truth cannot be beaten by the logic of the old scientific, analytic rationality.

Every critique that tries to demystify these new truth claims as they are is met with narcissistic, defensive aggression. Every critique is felt as an attack on our fragile personalities, not on our version of the truth. So it is all about truth, and at the same time, it is not about truth at all. Truth becomes something that needs to keep us sane and safe. The factual truth can be ugly, but the idealistic truth can create utopia in the most miserable places in the world.

This can be seen in various new social movements, ranging from MAGA to Cancel Culture. It is the acceptance of ideals that gives us orientation and therefore a base for safety, but as it is a way of our own choosing, we keep ourselves blind to the fact that this form of truth serves as a tool to dominate and manipulate us. If, with this kind of truth, we can dominate others, we do not mind being dominated in the first place.

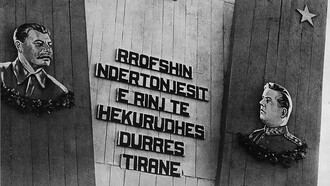

So the old version of truth is replaced by the axiological truth, which pays little respect to facts and scientific endeavors with the truth. For example, in the wake of the Brexit campaign, the Leave side's misleading claim that the UK sends £350 million a week to the EU, intended for the NHS, significantly swayed public opinion despite being debunked by the UK Statistics Authority. Similarly, during the 2016 US presidential election, fake news stories favoring Donald Trump proliferated on social media, with a study from Stanford University and New York University showing these stories were shared four times more than those favoring Hillary Clinton.

The anti-vaccination movement exemplifies how emotional appeals and misinformation can override scientific evidence. A study in Vaccine highlighted the influence of vaccine misinformation on social media, contributing to vaccine hesitancy, which the World Health Organization lists as a top global health threat. Climate change denial persists despite a 97% consensus among climate scientists, as reported by the IPCC, due to disinformation campaigns.

What can we do in the face of all that? The rise of a post-truth society reflects a shift from instrumental to axiological rationality, where emotions and values increasingly drive our understanding of truth. This transition, while unsettling, is not unprecedented; it echoes Max Weber's distinctions and reveals the enduring complexity of human rationality. As we navigate a world where subjective truths often overshadow objective facts, recognizing this duality is crucial. Science and rational discourse must adapt by acknowledging and addressing not only the axiological dimensions of truth but also the reasons why it is more attractive than an instrumental one. By doing so, we can better equip society to discern and resist the manipulative forces of populism and ideology.

The path forward lies not in lamenting the loss of an instrumental truth but in engaging with the realities of how truth is constructed and perceived today. Only through this engagement can we hope to restore a balance between emotional resonance and factual integrity, ensuring that truth, in all its forms, remains a guiding force in the future.