In 1946, when Josef Haubrich transferred his art collection to the City of Cologne immediately after World War II, it seemed to Cologne’s residents like a dispatch from a better world.

Long believed to be lost, paintings by German Expressionists and other exponents of Classical Modernism who had been persecuted during the war and denounced as “degenerate” suddenly belonged to the city’s residents. That with it Haubrich would lay the cornerstone for the collection of the Museum Ludwig—and thereby for one the most important museums for modern and contemporary art in Europe—still lay in the distant future.

Today, thanks to a generous donation from the Cologne lawyer Haubrich, the Museum Ludwig holds one of the most important collections of Expressionism in Europe, also incorporating the New Objectivity and other trends of Classical Modernism. Already in the 1920s Haubrich began compiling works by contemporary, and predominantly German artists, including such highlights as the Portrait of Doctor Hans Koch by Otto Dix (1921) (the very first modern painting in the collection) and The Dreamers (1916) by Emil Nolde, as well as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s famous Half-Length Nude with Hat (1911), which was exhibited at the Venice Biennale as early as in 1925. Among the collection’s major works are also pieces by Marc Chagall, Karl Hofer, Heinrich Hoerle, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, and Paula Modersohn-Becker. Watercolors represent the nucleus of the collection and paintings its substance, while sculptures round out the works.

The Museum Ludwig also houses an important collection of works by Max Beckmann, in particular from the Lilly von Schnitzler Bequest.

Exactly thirty years later, another spectacular gift caused a sensation and led not least of all to the founding of the Museum Ludwig as an independent institution: in 1976 the collectors Peter and Irene Ludwig donated their inimitable collection of American Pop Art to the City of Cologne, with the stipulation that the city build an independent museum for the new collection.

As early as in the mid-1960s, Peter and Irene Ludwig became enthusiasts of the art of American Pop artists, who were still completely unknown in Germany and revolutionary, first capturing the public’s attention at documenta 4 in Kassel. Along with Roy Lichtenstein’s famous blonde in M-Maybe (A Girl’s Picture) (1965) and Claes Oldenburg’s Soft Washstand of the same year, Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude No. 98 (1967) also made its way from documenta directly into Peter Ludwig’s collection. Today they are among the highlights of the Museum Ludwig’s permanent collection and thus part of the largest Pop Art collection outside of the United States. The Ludwigs—who had up to then collected chiefly ancient and medieval art—were fascinated by the immediacy and freshness of the artists’ approach to reality. Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns were of their own generation; their works embodied a modern attitude toward life and conveyed a sense of the here and now that was strikingly different from the timeless quality in the oeuvre of Picasso, whose works Peter and Irene Ludwig had collected with comparable intensity.

The Museum Ludwig’s collection cannot be adequately described without discussing the works that it houses by the century artist Pablo Picasso. Thanks to three donations by Peter and Irene Ludwig—the last on the occasion of the institution’s reopening after the Wallraf-Richartz Museum moved into a new building of its own—Cologne now has the third largest Picasso collection in the world after Paris and Barcelona. It comprises not only paintings from all of the artist’s creative periods, such as the Harlequin (1923) and Woman with Artichoke (1941), but also numerous ceramics and sculptures, including the original plaster piece Woman with Pram (1950) and the monumental head of Dora Maar.

That throughout his lifetime Picasso placed a great deal of value in drawing and graphics within his oeuvre is also demonstrated in the Museum Ludwig collection: it is the only public institution to own all three large print cycles by the master, the Vollard Suite (1930-37), Suite 345 (1968), and Suite 156.

Besides American art, the Ludwig’s comprehensive collection of Russian Avant-Garde art from 1905–35 also made its way to the Museum Ludwig as a gift. Artists such as Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Alexander Rodchenko, and Kazimir Malevich believed in the utopia of an art that was meant to serve a classless society. Today, they and many of their contemporaries are represented in the Museum Ludwig, which, with over 600 works, boasts the most important public collection of Russian art in the West.

Mark Rothko’s luminous color fields and Frank Stella’s geometric pattern paintings, along with Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings and Morris Louis’s reductive, colorful color stripes are just a few examples of the Museum Ludwig’s significant collection of abstract tendencies from the 1960s. It is not only comprised of paintings, but also includes three-dimensional works by Minimal and Conceptual artists such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Eva Hesse, and the abstract sculptures of David Smith.

Moreover, the Museum Ludwig’s collection reflects early abstract tendencies of the 1950s and 1960s in Europe, featuring works by, for instance, Jean Dubuffet, Lucio Fontana, Pierre Soulages, Wols, and Hans Hartung. Artists of the German Art Informel, such as K. O. Götz or Bernard Schultze, whose estate has been preserved in the Museum Ludwig since 2005, are likewise represented.

As American Pop Art also became known in Germany in the mid-1960s and was shown in this country for the first time with the exhibition Kunst der sechziger Jahre—Sammlung Ludwig (Art of the Sixties—The Ludwig Collection) at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, it did not go unnoticed by the Rhineland’s younger generation of artists. Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke referred directly to this completely new art from the United States in their works. Polke adopted the motifs of Pop Art, highlighting their arbitrariness in order to question any sort of content-related meaning they might have, while Richter, like Warhol, used photographic images from the media and private sphere to then enlarge them in “blurred” fashion in his paintings. Both artists were discovered very early on by the Ludwigs and today are represented in the museum’s collection with major works. In the 1970s and 1980s the Rhineland, and Cologne and Düsseldorf in particular, developed into a center of international artistic activity, something also reflected in the museum’s collection: if the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, with its professor Joseph Beuys, played an important role in forging a new, genre-crossing art—Beuys and, for instance, his student Jörg Immendorff are represented in the Museum Ludwig with major works—the “hunger for pictures” also helped the painting of A. R. Penck as well as Georg Baselitz and Markus Lüpertz gain recognition. In the 1980s the Museum Ludwig acquired key groups of works by all these the artists. Around the same time, a new generation began pursuing novel artistic perspectives with anarchic wit and subtle humor. The works by Martin Kippenberger, Markus Oehlen, Georg Herold, and Rosemarie Trockel in the Museum Ludwig’s collection are among the leading examples of contemporary art.

In dialogue with the collection, new courses have been continually set up to the present. In the last decade, for instance, the collection’s focus on painting has been supplemented by important sculptures and installations acquired from artists such as Georges Adéagbo, Stephen Prina, Cady Noland, Isa Genzken, and Phyllida Barlow. International artists whose works and exhibitions were influential in the Rhineland in the 1990s, including Andrea Fraser, Christian Philipp Müller, Christopher Wool, and Mike Kelley, are now also represented in the collection. In addition, contemporary art is continually integrated with targeted purchases of works by young artists. Today, new critical developments in painting, exemplified by Lucy McKenzie, performance pieces like those by Roman Ondak, and video installations by Clemens von Wedemeyer enrich the collection.

In 1986 the Museum Ludwig established its Video Collection in order to emphasize the independent status of artistic works in moving pictures. Indeed, as early as in the 1970s and prior to the founding of the Museum Ludwig, films by Bruce Nauman, Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, and Bruce Conner, entered into the collection of the Wallraf-Richartz Museum and are now housed in the Museum Ludwig. Today, all films, videos, sound installations, media art, and performances are collected and exhibited as part of contemporary art.

The Museum Ludwig’s Graphics Collection houses around 3,000 drawings and nearly 10,000 graphic works—holdings that are owed chiefly to benevolent supporters. One area of emphasis is Expressionism; another is represented by the graphic works of Picasso.

Moreover, the museum also houses the collected editions of Marcel Broodthaers, Sigmar Polke, and Lucy McKenzie. The collection is continually kept up to date through purchases and donations of works by, among others, Georg Baselitz, David Shrigley, Sister Corita, Maria Lassnig, Bethan Huws, and Caroll Dunham.

The Museum Ludwig is among the first museums of modern and contemporary art to have established a collection devoted entirely to photography. The department of photography was founded in 1977—today it preserves one of the largest and most important collections of photographs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (more about the Photographic Collection).

In recent decades, the collection has been brought up to date via purchases and gifts, including works by Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Wolfgang Tillmans, Christopher Williams, and Sherrie Levine.

Time and again, the Museum Ludwig revives the tradition of collecting and donating. The large exhibition on the occasion of the institution’s reopening—Museum unserer Wünsche (Museum of Our Wishes, November 11, 2001–April 28, 2002) organized under Director Kasper König—appealed directly to the public spirit of Cologne’s residents and to all museum visitors to actively take part in the formation of the permanent collection and to purchase selected works of art to donate them to the museum. Since then the collection has been consistently expanded with substantial pieces of contemporary art.

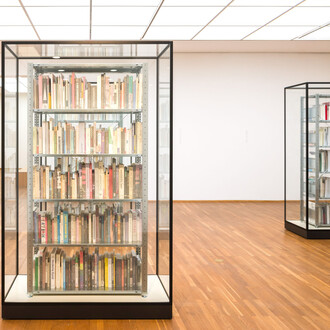

In October 2013 Director Philipp Kaiser is unveiling a new presentation of the collection, bringing treasures out of storage and displaying new acquisitions. The assertive title Not Yet Titled makes it clear that the museum is a place where the history of art is viewed from the perspective of the present, and perpetually perceived, evaluated, and also rewritten anew.