Dolby Chadwick Gallery is thrilled to present The trouble with flowers, an exhibition of new paintings by Elizabeth Fox.

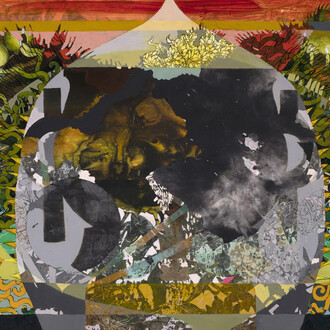

This exhibition is a theatrical treat as Fox’s narrative paintings seamlessly merge pop culture and art history. She playfully blends pop art with Botticelli, 50s sex icons with contemporary drag, queer culture with Americana. Her surreal scenes hum with a coy overtone as fine-lined figuration and blooming buds fuse in this singular suite of paintings.

Jayne Mansfield, actress and playboy playmate of the 50s and 60s, and Mickey Hargitay, her bodybuilder husband, make several cameos in this exhibition. Their overtly sexual, campy personas appear in The day we knew, where Mansfield poses scantily clad on the beach and Hargitay leers as he swims to shore. The verve and vigor of their hypersexual connection stands out against a landscape of twilit tones and an ominous aircraft. They are unfettered by the gloom around them. For Fox, the two are “very life” — bursting with vivacity, pleasure, and buoyant simplicity. They overthink nothing; they overdo everything.

In Life in the peonies, also featuring the tabloid couple, and Shablam in the poppies, Fox ventures into a pop sensibility. In each work, big, blooming flowers fill the background of the panel, and an emblem of unabashed vitality shines at center stage. A “shablam," in drag, is a move in which a queen drops with one leg in the air as the rest of her body hits the ground. It is sudden and spectacular in the truest sense of the word. It activates what Fox calls “the BAM of life,” the scintillating joy and striking fullness of the moment.

Fox’s paintings, crucially, do not aim to talk of the highs of life in absence of the lows. In She catches her own Lyft, for instance, a ghostly doll looks back at an image of her more youthful self as she floats by the fountain of life. She reaches in front of her towards two posts: an orange burst symbolizing calamity and anxiety, and just beyond, a cloud symbolizing emptiness, peace, and “god” in the sense of pure spiritual being. This Barbie-esque figure floats through the complete picture of life, struck by its bigness even in the minutia of calling her Lyft.

Many figures in Fox’s work appear as apparitions. In Kitty in the weeds, for instance, a sirenlike image of beauty appears in Fox’s backyard. The figure here is an amalgamation, a sort of Frankenstein’s monster of beautiful beings. Her face is that of Naomi Smalls, a drag queen who pulls her name from Naomi Campbell and Biggie Smalls. The body is Botticelli’s Venus, the legs are Jayne Mansfield’s, and the hand clutching the cat is that of Michelangelo’s David. She is an icon of timeless beauty beckoning from another world: a stunning impossibility.

When considered spiritually, there is no trouble with flowers, nor beauty, nor temporary bliss. Flowers live and die, ephemeral beauties subsiding quietly with time. But through the inescapable lens of humanity, flowers confront us with the flux of life and subsequent death as they drop petals in our gardens and on our kitchen tables. For Fox, the meat of life comes from this fullness. The fabric of joy is interwoven with sorrow, but therein lies its beauty. This is the BAM of life — the shock and awe, the startling wholeness, the fantasy of reality.

Elizabeth Fox was born in Orlando, Florida. She attended the Ringling School of Art in Sarasota before she moved to New Orleans and eventually to Maine where she currently resides. She has exhibited her work in New York City, New Orleans, San Francisco, Miami, Washington DC, Houston, the Netherlands, and at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA). This is her second solo exhibition at the Dolby Chadwick Gallery.