Green space is defined as land that is partly or wholly covered with trees, shrubs, grass, or other vegetation. This includes city forests, urban parks, trails, community farms, rooftop gardens, and shrubs and grass replacing streets. Adding trees to land increases the carbon captured by the growing trees. The land beneath the trees benefits from absorbing water rather than creating runoff, as on the cement and asphalt typical of the streets. Less flooding occurs because less water accumulates on the surface. The green spaces, particularly the large ones, have a higher air quality because they are more distant from automobile pollution. Shrubs and grass used to replace streets or other impermeable surfaces capture less carbon, but the soil beneath the plants retains the water and can be collected.

Given increasing weather disasters and climate change, every country and most cities have created new kinds of green spaces, giving them new meaning. This is possible because the health benefits of frequenting a green space are comprehensive and well-documented. A recent review and meta-analysis of 143 studies in 20 countries shows that living near green space is associated with multiple health benefits, including type II diabetes, cardiovascular mortality, diastolic blood pressure, salivary cortisol, heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), HDL cholesterol, incidence of stroke, hypertension, dyslipidemia, asthma, and coronary heart disease1. Public spaces with exercise facilities are improving the health of nearby residents. Trees help diminish atmospheric pollutants, lessen the urban heat island effect, and alleviate stress and sleep disturbance by providing a buffer against traffic noise. Studies have also found a correlation between visiting green areas and a boosted immune response. There are such widespread benefits that the availability of green space for everyone is becoming a key parameter of urban planning, and Europeans are concerned about its distribution and access2.

Conservatives and liberals alike usually agree on the importance of new green space. This is an essential reason for the newfound popularity and experimentation of green spaces worldwide, and here are some examples.

The first works related to silvicotherapy go back to antiquity. According to Pliny the Elder, "the smell of the forest where peach and resin are collected [therefore coniferous forests] is extremely salutary to the phthicists and to those who, after a long illness, have difficulty recovering.” In the Middle Ages, terpenoids present in the forest atmosphere, especially conifers, were used as analgesics, sedatives, bronchodilators, antitussives, anti-inflammatories, and antibiotics3.

With two-thirds of their country covered with forests, the Japanese were the first to formulate “forest bathing.” The term Shinrin-yoku was coined in 1982 by Mohide Akiyama, Director of the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. He knew of the findings showing the beneficial health effects of the compounds, such as phytoncides and the essential oils that pine, oak, eucalyptus, and Sophora genus emit. Thus, he officially put forward Shinrin-yoku as a recognized practice, promoting its benefits to the Japanese public and establishing guidelines for its implementation.

Shinrin-yoku was also developed in response to Japan's increasing urbanization and technological advancements. It was put forth to inspire the Japanese public to reconnect with nature and as a means to protect the forests4. If people spent time in forests and could find therapeutic comfort within them, they would want to protect them.

The practice can be as simple as walking in any natural environment and consciously connecting with what’s around you. It can also be more challenging with longer, more complex trips.

Forest therapy involves using a therapist and the five senses, letting nature enter. Some examples of exercising this include:

- Listening to forest sounds, i.e., birds and insects.

- Touching the ground, the trees, and the leaves.

- Smelling the flowers and other essential oils of the plants and trees.

- Observing the surroundings and scenery.

- Tasting the crispiness of the air while breathing.

Therapists may be trained guides or psychologists, and the experience is compatible with yoga, Zen meditation, and self-awareness techniques.

Adirondack Park is an area in New York where you can try forest bathing and therapy. Certified forest therapy guides are available year-round at Adirondack Riverwalking for Lake Placid, Saranac Lake, and the Wild Center, an award-winning natural science museum of the Adirondacks. The fall foliage and snowshoeing in winter are peak experiences.

The planting of trees is a significant opportunity that is being chosen by many cities. It makes forest bathing, therapy, and enjoyment possible for millions, reducing atmospheric carbon and helping water and heat management.

The Seoul Metropolitan Government planted 8.27 million trees in 2019 in various city areas, including small pieces of land and vacant lots. This exceeded the city's annual target of $5 million. The city planted 15.3 million trees between 2014 and 2018 and decided to plant an additional 15 million trees between 2019 and 20225. Recently, Mayor Oh Se-hoon outlined his "Garden City Seoul," an initiative to transform the capital into a global garden city where people can visit easily by vacating numerous decrepit downtown structures6.

Due to the city's past efforts, Seoul's park composition rate (28.53 percent in 2022) and park area per capita (17.74 square meters in 2022) have soared. However, the area of local parks (within a five-minute distance) measured merely 5.65 square meters per capita, resulting in a shortage.

The initiative is realized following four strategic concepts:

- Emptiness: emptying out jam-packed spaces to create public urban green spaces. The City is set to transform its landscape, vacating high-density spaces and replacing them with resting places.

- Connecting: severed green belts to create public urban green spaces.

The City plans to connect partially dispersed rest areas and create additional green spaces close to citizens. By 2026, the City will focus on building a new green path from 286.6 km to 2,063.4 km.

- Ecology: conserving the natural environment around the Hangang River and nearby mountains and streams to create ecological gardens with natural scenery.

- Sensibility: new landmarks with high-quality flower gardens mixed with sensibility and culture. Like the RHS Chelsea Flower Show and the International Garden Festival of Chaumont sur Loire, a city's garden can become a tourist attraction. Likewise, gardens in Seoul will be raised with good care and turned into culture and projects representing the City.

Freiburg, Germany, is active in creating green spaces and has an even greater green density than Seoul. Freiburg’s parks, green spaces, recreational facilities, playgrounds, roadside greeneries, and the Mundenhof add up to an area of 397 ha (3.97 km2), corresponding to 18.05 m2 of green space per Freiburg citizen. On average, major cities in Baden-Wurttemberg have 22.66 m2 of green space per citizen. However, there is an area of 2600 ha (26 km2) of forest near Freiburg and additional recreational areas like the Rieselfeld district (a former sewage farm). Most green spaces came into existence in the 1960s.

“Sponge city policies are a set of nature-based solutions that use natural landscapes to catch, store, and clean water; the concept has been inspired by the ancient wisdom of adaptation to climate challenges, particularly in the monsoon regions in southeastern China."8 They were theorized by the Chinese architect Kongjian Yu (9) and have spread internationally, as seen in the excellent video Sponge Cities. They are part of a worldwide movement that goes by various names: "green infrastructure" in Europe, "low-impact development" in the United States, "water-sensitive urban design" in Australia, "natural infrastructure" in Peru, and "nature-based solutions" in Canada. As reported in the video on sponge cities, infrastructure is expensive, and the guidelines are complex and vary from city to city.

Streets and other hard-surfaced areas may be replaced by plants with water-absorbing soil and drainage systems. This concept is often applied to new parks and plazas. They rely on nature as much as possible, and the drainage part is more costly but necessary to address the general problem of climate adaptation and water management in urban areas. We are reminded that the longer we delay mitigation, the more the adaptation costs will increase, probably non-linearly.

The advantages of sponge cities include the capture and reuse of rainwater, the reduced chance of flooding, the improvement of the overall water quality, and the reduction in the intensity of urban heat islands. The green spaces are increased with the accompanying health benefits.

“Shanghai's growing number of parks and greenbelts are part of its Five-Year Plan (2021–25) to become a "city of ecology," but they are also intended to operate as "sponges"—to a absorb drainage as well as collect and purify rainwater. The city's largest sponge park, "Starry Sky," was also open to the public in August. The 54-hectare park has 38 hectares of land and 16 hectares of water. Along with typical designs like permeable pavement and rainwater gardens, it also has a landscape ecological corridor, sponge ecological wetland, urban rainwater storage, and purifying facilities." 8.

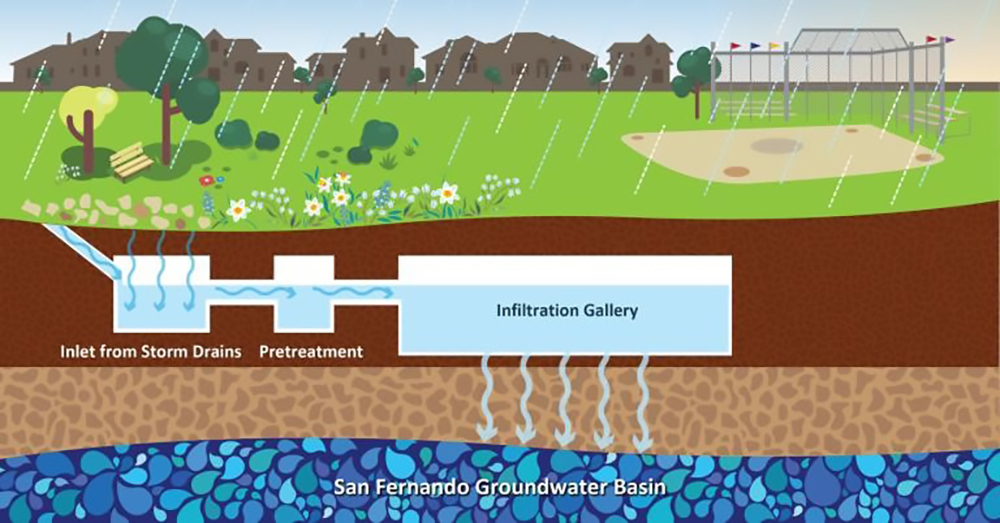

Boston and Los Angeles have initiated sponge work. Between February 4 and 7 this year, LA captured enough stormwater to provide water to 106,000 households for a year. The water flow diagram of the LA neighborhood stormwater capture project' is shown below.

Neighborhood stormwater capture projects are an important part of helping LADWP increase the City’s local water supplies and reduce its dependence on more expensive, imported water from Southern California. Collectively, these projects will more than double the average stormwater captured from about 21 billion gallons annually to more than 49 billion gallons annually by 203510.

Boston has a unique idea of using curb extensions to incorporate infrastructure such as porous asphalt, rain gardens, infiltration tree pits, and groundcover wildflowers to improve rainwater management.

Other creative initiatives include smaller (pocket) forests, such as the Manhattan Healing Forest, which is dedicated to creating additional green spaces that emphasize biodiversity.

The trees create a microclimate, filter dust particles, and provide shade and protection from acoustic pollution. Two large buildings have been constructed to date.

Finally, we have a rooftop farm in Brooklyn dedicated to growing vegetables. It produces 30,000 lbs. of vegetables per year and can manage more than 175,000 gallons of stormwater in a single rainfall.

In conclusion, momentum for more urban green space has grown in the last decade, and experimentation is increasing. People of different political backgrounds can enjoy forest bathing, forest therapy, and the numerous health benefits. We can unite with each other in our love of green spaces. We can build more urban forests and parks with cultural meeting places, construct more sponge cities, and reach out to the global community in adaptation.

References

1 Twohig-Bennett, C., Jones A. (2018), The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes, Environmental Research, Volume 166, Pages 628-637.

2 O'Sullivan, F. (2021, October 17). Europe’s greenest cities might not be the ones you think. BloombergCityLab.

3 Société d'Écologie Humaine, (Ed.). (1999). L'homme et la forêt tropicale: Travaux de la Société d'écologie humaine. Châteauneuf-de-Grasse: Éditions de Bergier.

4 Fitgerald, S., (2019), The secret to mindful travel? A walk in the woods, National Geographic, Travel, October 18.

5 Korea Bizwire. (2020, March 27). 8.27 mln Trees Planted in Seoul Last Year.

6 Seoul Metropolitan Government. (2013). Mayor’s Speech: Seoul's roadmap to expand the City's urban green spaces. February 6, p. 1.

7 Jiayun, K. (2021, October 14). Shanghai banking on sponge parks to become City of Ecology. Shanghai Daily Shine.

8 Wikipedia. (2024). Sponge City. Page 1.

9 Frontiers (June 14, 2021).

10 Los Angeles Department of Water & Power. (2024). Other Stormwater Capture Parks.